Jewdar doesn’t know if Koch, Neil Barsky’s new film about Ed Koch, is a good documentary, but it is an enjoyable one. We are not being glib or critical here. If you are looking for major revelations about New York’s garrulous ex-mayor, look somewhere else. In many respects, the Koch of Koch is the Koch of interviews and headlines. Yes, we do get interviews with friends, foes and colleagues, but to a great extent, there’s a sense that what you see is what you get. But that’s neither a bad thing, nor is it a result of inept film-making.

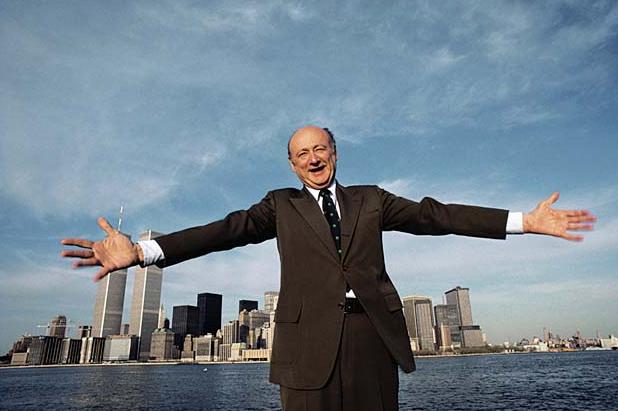

This is not, it should be noted, a documentary about Ed Koch. It is a documentary about Mayor Ed Koch. There is almost nothing about his life before the mayoralty, or at the very least, before his life in politics, where you could see him thinking about the mayoralty, nor, for someone who has maintained a fairly high public profile in the quarter century since he left the mayor’s office, is there much about life after Gracie Mansion. But that is as it should be, since Ed Koch, whatever else he may have been, was the mayor.

Jewdar was too young to have appreciated, and too Midwestern to have experienced the Koch mayoralty, or appreciated what it meant. But we have seen The Warriors, Escape From New York, and both Deathwish and Deathwish III, so we do understand what New York was like in the years before Koch (spoiler–it wasn’t good). For those who are critical of Koch’s tenure, one might want to consider that, while he clearly craved the office, he also clearly cared deeply about the city, and about improving the lives of the people who lived here. Not just protecting them, or enriching them, but making their lives better.

The one little tidbit about pre-political Koch, where he talks about the economic difficulties of his childhood, is telling. Koch is a liberal, but one whose liberalism is experiential, not ideological. It is a liberalism that does not necessarily gibe will with a Democratic liberalism that has to a great extent moved away from identification with white working class concerns to black and Latino underclass concerns. It is also a liberalism that is tempered by political realism as opposed to ideological purity. The Koch of Koch is not one that we always agreed with, but he is one that we can respect.

This being Jewdar, we do feel compelled to mention the weird Jewish scene, which was either staged or reflects some odd Koch family customs. Koch visits his sister and her children and grandchildren for what is called “Yom Kippur Break Fast,” but it’s clearly daytime, and they light the candles and make a brocho on the Yontiff candles. But nobody elected Koch because of his meticulous halachic observance.

Nostalgia is a dangerous trap to fall into, and Koch certainly had and has his problems and faults, and many of the criticisms that appear implicitly or explicitly are perfectly valid (there’s a great point in which the film talks about Koch going South in 1964 to do civil rights work as a lawyer, and then has him talking about how this was a good political move). But accepting the tendency to remember things as better than they really were, we can nonetheless look at the last few people who sat in his chair in City Hall, and understand why, as the film makes clear, compared to the CEO, the Prosecutor, and the Pacifier, Koch was, and in the minds of many will remain, the Mayor.

Leave a Reply