Jews and comics have been connected in my mind since the early 80s when I used to slide the latest Avengers or Justice League issue inside a Hebrew school book and sit in the back lost in the cosmos. Tribe and passion were further entwined at my Bar Mitzvah, when each guest table was named after a super team (I refused to let my parents also give numbers), so, Uncle Meyer had to wander asking-with-accent for the “New Teen Titans” table, identified only by an actual comic sticking out of a centerpiece. Turns out the connection goes back even farther then these personal phenomena, back to the beginnings of the art form itself.

This Thursday, September 24, at the 92nd St Y comics historian Arlen Schumer, author/designer of the essential-for-fans The Silver Age of Comic Book Art presents a “VisuaLecture” on ‘Jews ‘N’ Comics’ in which he “surveys the Jewish influence on the creation and development of the superhero, the significant contributions Jews have made to the creation of the comic book itself, and the evolution of comic book art in the 20th and 21st centuries.”

He’s been touring this dynamic uberspiel for a few years now, of course including superhero creators like Siegel & Shuster (Superman) and Kane & Finger (Batman) as well as the likes of Harvey Kurtzman (MAD), Will Eisner (The Spirit), Harvey Pekar (American Splendor) & Art Spiegelman (Maus), pioneers of underground comix and the literary “graphic novel.”

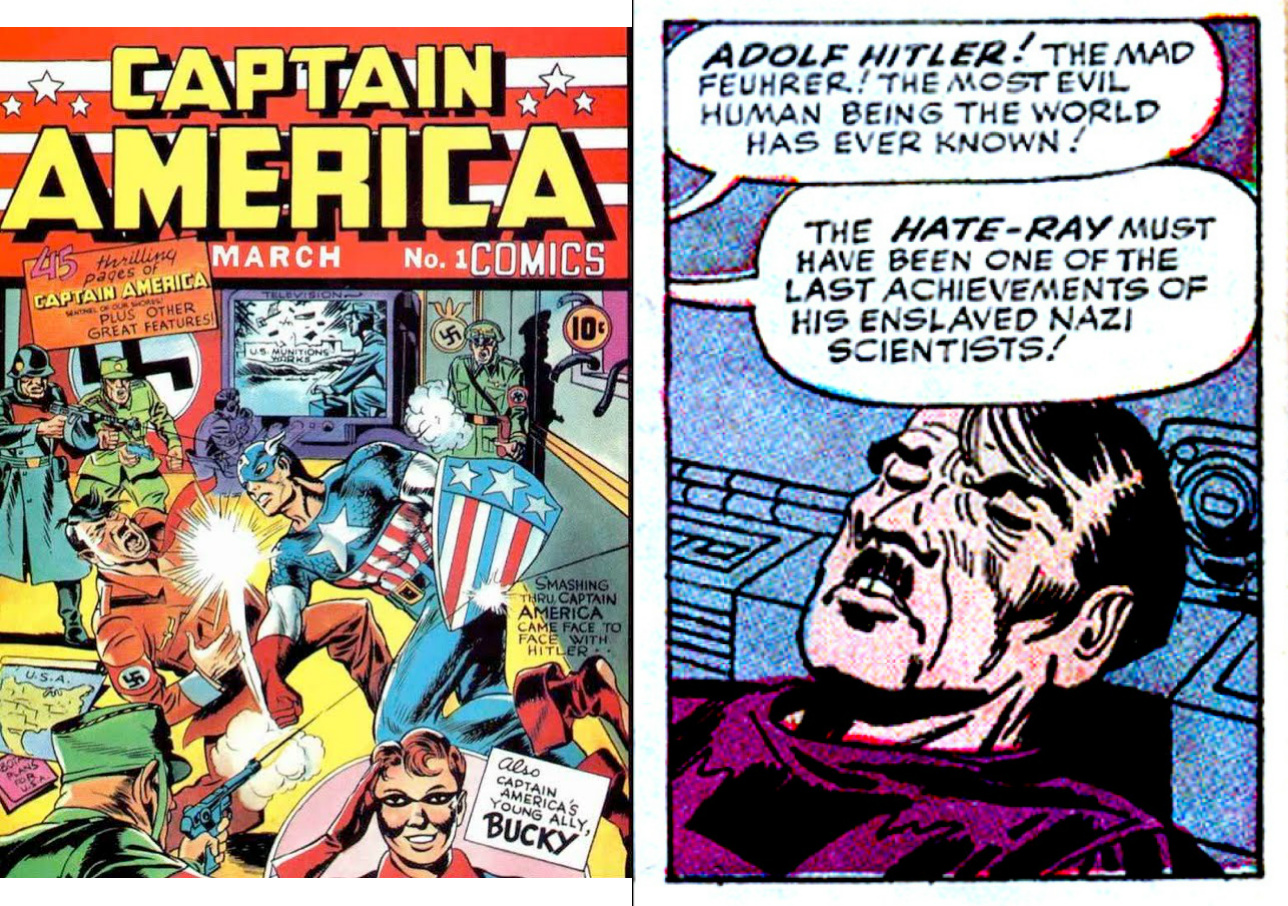

This being the Days of Awe, the choice of which Jew In Comics to ask Arlen about was clear: Jack “King” Kirby a.k.a. Ya’akov Kurtzberg, the visionary artist who drew Captain America punching out Hitler a year before Pearl Harbor, who manifested the Marvel Universe in the 60s, by co-creating, with writer Stan Lee, the Fantastic Four, X-Men, Silver Surfer, Hulk, Thor and more, and who went utterly mythic in the ’70s with his psychedelic sci-fi Fourth World series of comics for DC: New Gods, The Forever People and Mister Miracle.

If you didn’t already know, would you be able to tell from Kirby’s oeuvre that he’s Jewish? What themes and situations strike you as particularly Jewish in his work, if any.

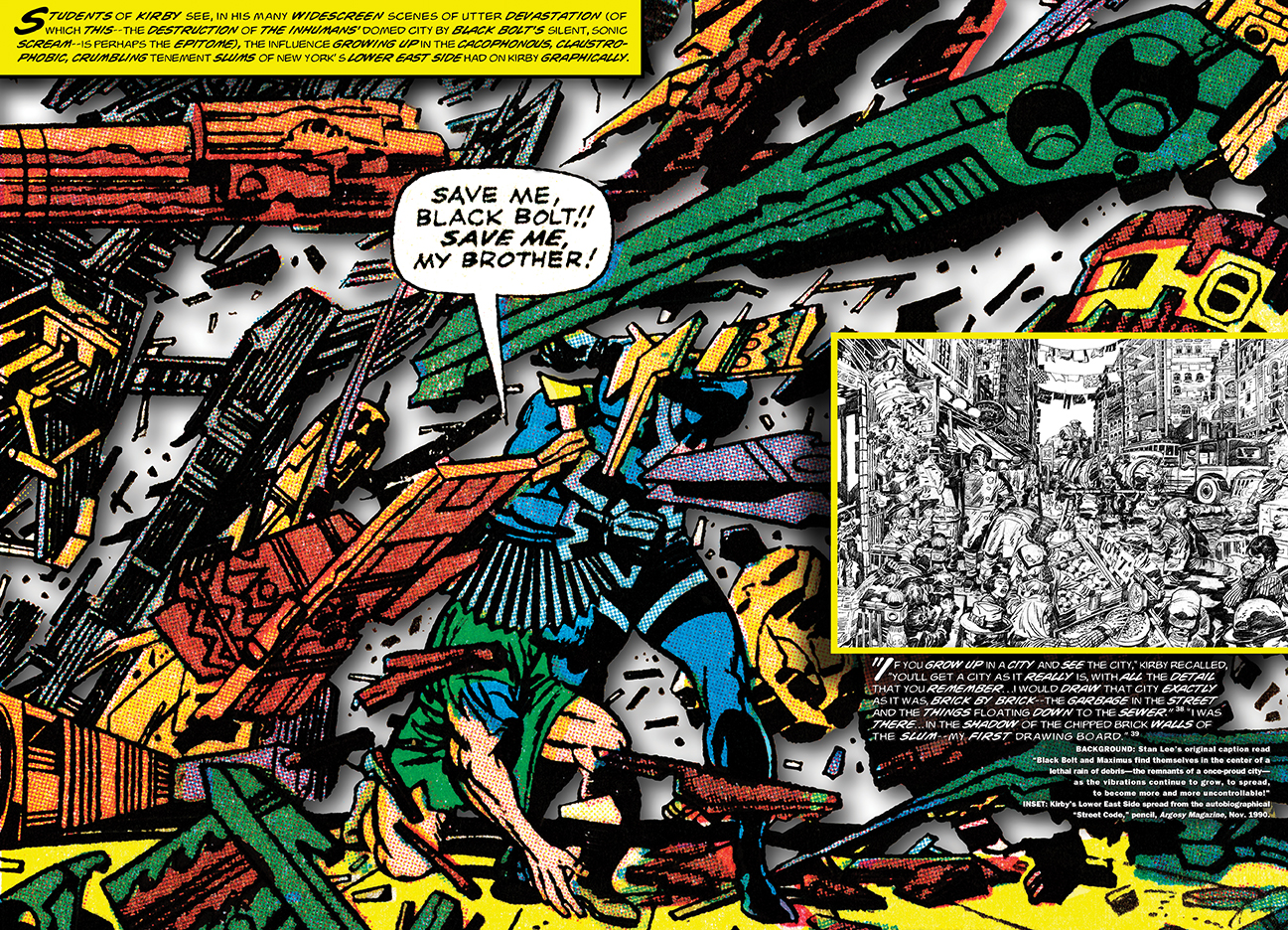

Well, like so many Jewish entertainers in the mid-to-late 20th Century, Kirby covered up his Jewishness in his work, yet it couldn’t help but come out in specific instances—like Fantastic Four #21 (Dec. ’63), “The Hate-Monger” story—a thinly-disguised indictment of the Ku Klux Klan during the rise of the Civil Rights era. Or his epic “Man-Gog” saga that he did in Thor #153-157 in 1968. The name Mangog was probably derived from the biblical Magog, a grandson of Noah, but is more commonly associated with an apocryphal biblical story of Gog and Magog, in which Gog, one of the fallen angels of a nation called Magog, represents an apocalyptic coalition of nations arrayed against Israel. In other biblical traditions, Gog and Magog are variously presented as supernatural beings like giants or demons, and even in the Koran they are described as “evil and destructive in nature” and causing “great corruption on earth.”

Such a monstrous being, swathing a path of total destruction across Asgard, could only represent, to a war veteran of the European theater like Kirby, the Blitzkreiging Nazi war machine as it stormed over Europe, annihilating all who stood in its terrible path.

Was Captain America Kirby’s reaction as a Jew to what was going on in Europe in the early 40s or as an American or Both?

This gets into the classic question of “dual loyalty” that American Jews have always been subject to: are we loyal to America or Israel (similar to American Catholic politicians—most famously, JFK—being questioned about the allegiance to The Pope over America)? Since I believe that Israel is the 51st State—as the only democracy in the Middle East—and that America was founded on the Judaic (not “Judao-Christian” as is always referred to) principles of freedom and justice—then to “react as a Jew or as an American” is moot, because it is BOTH.

When they created Capt. America in early ’41, almost a year before America enters the war, Kirby and Simon were 2 American Jews trying to raise the consciousness of isolationist America about what was happening with the War in Europe’s Nazism and Fascism —and its implications for Europe’s Jews (which they were hearing stories about, as the Nazis moved across Russia in 1940, slaughtering Jewish communities whole; the concentration camps were not yet known about).

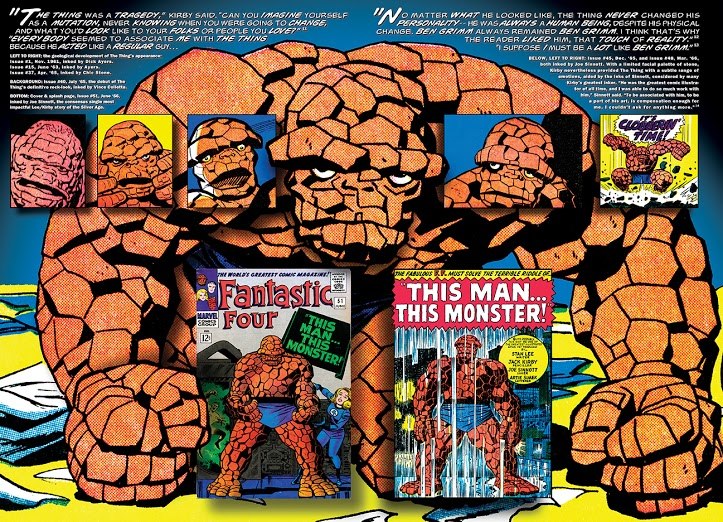

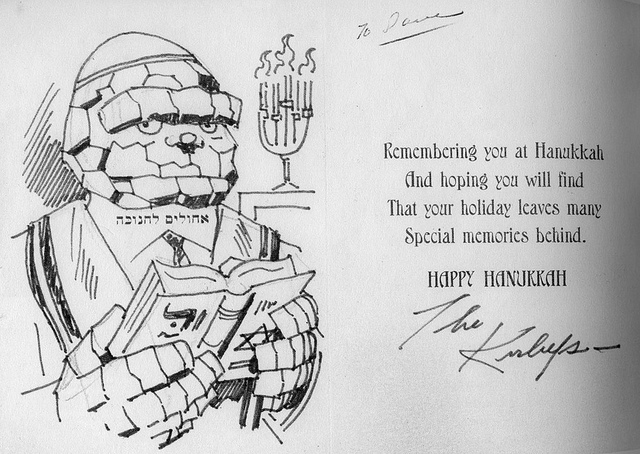

The Thing was eventually revealed as being Jewish — is this something you already knew or we could have guessed?

Again, The Thing was a mensch with super-strength, his Jewishness buried under all that orange-rock skin—in the same way that Jules Feiffer discussed Clark Kent being the ultimate assimilationist American Jew in his essay in his Great Comic Book Heroes (1965). Nothing was overt—one had to read between the lines (or the panels, in this case!).

The Thing, like Kent/Superman—is the perfect metaphor for the assimilationist American Jew, hiding his real self beneath a rock-hard surface.

Is there a Biblical influence in Kirby’s work?

Of course! In Thor 160-162, Galactus and Ego the Living Planet engage in a battle royale and he introduces a legion of alien nomads called the Wanderers, who were the first victims of Galactus ages before, and who have been wandering through space seeking revenge ever since. To see them as wandering Jews in a cosmic diaspora (minus the revenge), in light of the previous Mangog exegesis, is fairly overt. Especially when, at the climax, the Wanderers are left stranded on a triumphant Ego, though the planet itself is barren and incapable of sustaining life—until Ego (God?) transforms the planet into an Edenic paradise. This parallels the situation of the wandering Jews of the post-Holocaust, who settled in a desert wasteland and transformed it, relatively overnight, into the desert oasis Israel is today. And to complete the Judeao-Christian symbolism, Ego/God takes human form and bequeaths his planet to the Wanderers, telling them “…make of me your home…forever! Until the end of time.” Sound familiar?

Also, The Silver Surfer, who becomes the Fallen Angel whom God casts back down to earth after rebelling—and his New Gods is chock-full of Biblically-based characters like the patriarch Highfather, Isaak, et al.

How has Judaism / Jewishness influenced superhero comics in general?

The idea of the lone underdog (the superhero) fighting against the larger, societal menace is a very Jewish idea—David against Goliath, Israel against its Middle East “neighbors”—as is the ideas of helping the weak and defenseless—the Jewish concepts of charity and mercy—that we see in superheroes like Superman helping the weak versus lording it over them, as a super-despot would (Jewish editor Mort Weisinger most famously dealt with these issues in the classic 2-parter “Superman, King of Earth” in Action Comics #311-312 in 1964). Samson is a Biblical “superhero” with his kryptonite-like weakness (the cutting of his hair). And the myth of the Golem from 16th-century Prague’s Jewish ghetto informs ALL of the early superhero origin stories—creating a super-hero to “save the Jews”—as well as Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein 200 years after the Golem myth began.

*****

…And this is just the tip of the Goldberg! Check out Arlen’s “VisuaLecture” on ‘Jews ‘N’ Comics’ this Thursday, September 24, at the 92nd St Y be sure to adorn your coffeetable with The Silver Age of Comic Book Art.

Leave a Reply