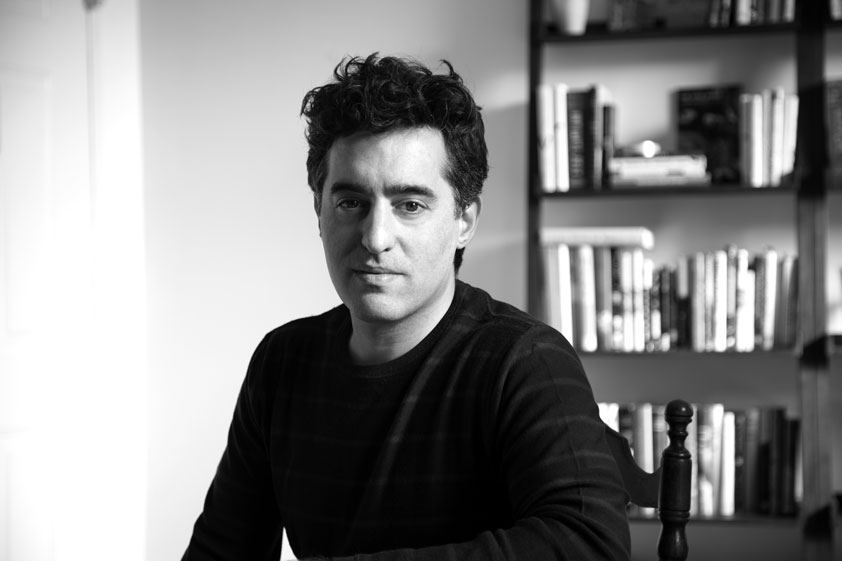

Former yeshiva bocher Nathan Englander is one of the most original voices in American fiction today. His first two books, For the Relief of Unbearable Urges and The Ministry of Special Cases, won him wide acclaim, and now he’s come out with a new collection of short stories, What We Talk About When We Talk About Anne Frank. He also translated the Hebrew for the New American Haggadah, a project he worked on with Jonathan Safran Foer. Englander’s play, The Twenty-Seventh Man, will be opening at the Public Theater in New York City this fall. Recently, we spoke by telephone.

You have two new projects. I thought we could start with the New American Haggadah. I’m wondering how the project came about, and why you felt compelled to translate. The introduction to the Haggadah says, “Our translation must know our idiom.” Your words?

That is very much Jonathan’s intro. He’s very big in this book on not having our names anywhere. I don’t think we’d even have our names on the spine if the publisher hadn’t made us. I didn’t feel compelled—I was compelled by Jonathan. He came to me about three years ago and said, “I know you’ve contributed an essay but what I really want is for you to do a complete new original translation.” A crazy idea considering I’m not religious anymore. I’d never translated anything past menus, I had zero experience, and did not want to engage in this way. And he just made it clear that this was something I, we would be proud of. And you know what, I’m really so happy to have played a part in this project.

Did it bring you back? Or provide some new connection with the religion as a whole, or with the Passover story?

It’s a general reflex to say, “Ah, you were religious and you’ve left the religion. Did working with this text bring you closer to the religious aspects of Judaism that you left?” I like to flip it immediately. I don’t go up to people who are super religious and be like, “Hey, are you done with this yet? I know you’ve been religious, but now you see that being not religious is better…” I am so thankful I can have my not-religious side. I am so thankful that God has put me on the path of irreligiosity. It is a great path for me, and all this deep study has only furthered my belief in how much I enjoy a moral lifestyle that is not traditional in the religious sense. But the project reaffirmed everything I believed in, which is I love books, I love texts, and I love the close study of texts.

So the Haggadah was the first thing you translated, and then you got started translating Etgar Keret’s new book, Suddenly, a Knock on the Door.

It was interesting to work with the Haggadah, where ninety percent of it is stuff from Tanakh. It’s really daunting to say, “Ok, let’s do the Kiddush.” You might sing it every week, you might drink wine after it, you might know it by heart, but it’s the creation story! And then, to read Etgar, who writes these beautiful straight-talk stories… Here I’d been doing all this Aramaic biblical translation and I thought, “What would it be like to do the most modern voice?” I did not work on the Haggadah with God—well, maybe I did, but I did not work on it directly with God, to ask, “What did you mean here?” You can’t say, “You know, I think the world should be created in seven days.” So it was interesting to work with Etgar, to tweak a word or tweak a sentence and have him be like, “What have you done here?!”

The idea that I had access to the original stories, that Etgar is a good friend… It was sweet, the other translators made room for me.

The title of your new short story collection is What We Talk About When We Talk About Anne Frank. And—we’re no longer talking about Anne Frank. We’re talking about what Anne Frank means to people who are pretty far removed from the Holocaust. Have we reached a different stage?

Anne Frank is in the title of the book, but it’s not about Anne Frank. Ever since I wrote the story “The Tumblers” [in For the Relief of Unbearable Urges], it hasn’t been about the Holocaust. It’s about how we remember the Holocaust. There was the Shoah, this horrible genocide that happened, and there are all the echoes that came out of it that changed the world and changed world history. And then there’s this strange thing which is the remembering of the Holocaust, the ownership of the Holocaust and the indoctrinating of brains and all this stuff—and that’s what I’m interested in.

Nobody had accents in my family. My parents were born here. My grandparents were born here. My great grandparents were born here. This idea of me, because of my yeshiva education, being raised as a first generation survivor’s kid—that’s from education. It didn’t happen to me. It didn’t happen to anyone in my family. So how is it that my brain functions like that? That’s what interests me. How we remember, who gets to own this memory, what gets done with it.

In your stories, there’s plenty of space for Jews to be ugly to other Jews. They don’t need people from the outside to make them ugly.

The only thing I’d qualify is that you can read it exactly that way. But this book functions like a Rorschach test. Somebody else reading this might say it’s beautiful or complex. My point is, I’m not intentionally calling anybody anything. In the story “Sister Hills,” everyone reads it differently. You can say, “Ah, this is why we need to be out of the West Bank,” or, “Ah, this is why we need a greater Israel.” That’s my dream about how stories should work.

People are human. There’s this idea of dirty laundry, and poor Philip Roth—I feel like I don’t get beat up so much because he got beat up for me. People used to treat him like, “The shandah! The bushah! The things you’re putting in the world!” But to me, the point of it is, I’m building worlds. Why is the Jewish world not a whole world or a complete world? It’s a whole universe and it will contain everything. That’s how I was raised. When I grew up they didn’t say to me, “This is a half-world or a fake world.” They said, “This is your universe.” So I feel like that’s the point—I’m telling a story and everything better be in the story.

The idea of people being human is no letting out of secrets. It corrupts the story if I’m being didactic, political, trying to change your mind. That’s not a story, that’s a pamphlet. What I pray for, what I work for, is that you should be able to read it and have a reaction, and make a judgment. It’s like the books that I fell in love with when I started reading. It’s about asking questions, not having answers. That’s why I still feel so close to Kafka or Camus, to Crime and Punishment. They’re asking really hard questions but you have to bring the answer. The story’s not bringing the answer for you.

For the New Yorker podcast series, you chose to read Isaac Bashevis Singer’s story “Disguise,” about a cross-dressing yeshiva boy in old Europe, and it reminded me of some of your own stories in this way that you’re comfortable enough to say, “This is a world. It has enough inside of it.”

My aesthetic is very simple: If a piece of art isn’t universal, it’s not functioning. It’s very strange that people want to ask Jews, “I’m not Jewish. My friends aren’t Jewish. Can I read this story?” It’s like Crime and Punishment. You don’t give that to someone and say, “Oh, you’re not Russian, you’ve never killed an old woman, so I don’t think this book’s for you.” Nobody’s worried about whether you can watch Star Wars without having been a Jedi. It’s a really strange notion that gets put very specifically on literature with lots of Jews in it, or with lots of black people, or with lots of gay people. That’s how I feel about [John] Cheever. Nobody in my family ever mixed a martini. That world is as foreign to me as a dybbuk is to someone else. And you know what, there’s no distance, I get everything. Nothing is lost on me. So yes, why would a Jewish world be less of a world, or too “other,” unless the writer has failed?

Leave a Reply