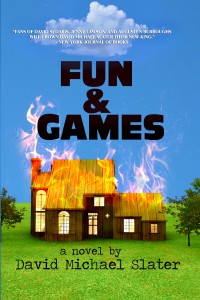

A Holocaust-survivor grandmother who makes macabre jokes. A famous father whose anti-religious books attract sexually-desperate groupies. Sadistic sisters, an alcoholic mother, an unusually high body count for a novel this funny, and a plot that encompasses Hebrew school, porn producer thugs and a faltering orgy for literary deconstructionists without missing a beat. Even more remarkable, David Michael Slater’s Fun and Games is a male coming-of-age story that doesn’t rely on shock humor or gratuitous offense for chuckles–it’s hilarious because it’s tragedy happening to somebody else, a boy named Jonathan, who in terms of teen hormones and bewilderment could have been us. In HEEB’s exclusive excerpt, below, Jonathan’s grandmother Myna visits his Hebrew school–SFW only if laughing out loud won’t piss off your boss.–Judith Basya, HEEB Literary Editor

*****

Sixty seconds later, the video had been returned to its drawer, and the class was sitting up straight, staring at both Myna’s blue velour running suit and the lavender scarf on her head, while Tziporah introduced her as a brave woman who had seen the kinds of things she prayed every night we would never know, but about which she had to make sure we knew, which is also why we’d been watching that awful movie.

“It is in March, 1939,” Myna said with no further ado. “I come here to America with my first husband, Nathan Schwartz, from Moravia, Czechoslovakia. We leave just weeks after Hitler’s armies come and call it part of their Protectorate. We have a tiny time to get away because the first ‘Protector’—he tries to pretend for a while that they weren’t there to murder us all good and dead.”

I started clapping. I didn’t mean to, but I thought it wasn’t absolutely impossible that she was done. There wasn’t all that much left to the story. Everyone turned and looked at me, so I stopped. But I could see from their eyes my clapping was the first interesting thing that had happened all class long.

Myna went on to tell how she and Nathan had owned and operated a small general store in Moravia for nearly ten years, then how they sold it in late 1938, even before their country lost its bordering territories (and thus all its defensive capabilities) because they could “read the letters on the wall.”

“Nathan was a pessimist, thanks to God,” Myna told my bored class. Then she added, “We are all of us pessimists now. Do you know why this is so?”

Receiving no response, she answered her own question. “The pessimists went to America,” my grandmother declared with a twisted grin and her finger in the air. “The optimists went to the gas chambers.”

I clapped again. Only four claps this time because Tziporah gave me the Major Screw Eye. Fortunately, no one appeared to be listening.

Myna looked a bit concerned about the lack of reaction she was getting, but nevertheless proceeded to share the boring story of her flight to America, the gist of which was that after selling their store, she and Nathan applied for visas with a group of extended family members. Neither had siblings or living parents. The Nazis had by then taken over, but somehow the applications were approved anyway. Myna ascribed this amazing good luck to the chaotic nature of those first uncertain weeks. “We could have been approved for tickets to the moon!” she cried. “Such numskulls, they were! No one knew who was in charge of what or what was in charge of who! All we needed was some money for a nice Jewish bribe, and poof! we are coming to America. Any questions?”

She was warming up. That last remark was a bad sign. Any minute now she was going to tell a Jewish joke. The world was about to find out that my grandmother, the Holocaust survivor, told Jewish jokes. But maybe she was done. There was no way anyone was going to ask a question.

Sarah Glickman raised her hand. I wanted to chop it off. Where was our broadsword when I needed it?

“Did you keep in touch with everyone after you got here?” she asked.

It was my impression that a dozen or so family members made the journey, though neither names nor exact numbers were ever made clear because the entire group wound up scattered across the country. We were never in contact with any of them, and Myna never talked about her relatives except to say they didn’t get along.

My grandmother shrugged. “To run for our lives—on this, we could agree, but nothing else. Once we got off the boat—What’s the point? Besides, most of us got different names when we arrived to Ellis Island.”

My grandmother shrugged. “To run for our lives—on this, we could agree, but nothing else. Once we got off the boat—What’s the point? Besides, most of us got different names when we arrived to Ellis Island.”

Sarah had no follow-up question, thank God. I prayed we were finally done, but someone else asked what Myna and Nathan did when they got to Pittsburgh.

Damn you all! I wanted to scream. You don’t care!

“Some money, we still had,” Myna explained. “We open a new general store in thirteen months, if you can believe! My son, Michael—he was born in 1944, but my Nathan died from cancer in the liver just a year later, so I run the business myself and raise him there. But then, many years later, I finally married to Jon’s grandfather, Leon.

I stood up and clapped like crazy. Show over.

“Jonathan!” Tziporah snapped. “What is wrong with you? Sit down this instant! This is your grandmother!”

I sat down. Myna winked at me. She was having a grand time.

“Did you say you married Jon’s grandfather?” someone asked.

“Yes,” Myna said. “I married to his mother’s father.”

All at once, the entire class un-slouched.

“So, his mother’s father married his father’s mother? Isn’t that, like, incest?”

Oh, we had buy-in now. Engaging curriculum!

“What is this word?” Myna asked. No one had the guts to define it for her.

My grandmother regarded the class with a slightly impish grin, which made the contents of my stomach churn. Maybe if I started choking to death—

“Children, let me ask you a question,” she said. “Show me what a smart bunch of kinderlach you are. In the desert for forty years, why did the Jewish people wander so long?”

I scanned the room. The door was blocked by too many desks. I could hurl myself through the window, though.

Myna had asked this “question” during dinner at our house a week earlier and almost made my father raise his voice. While Dad was famous for his opposition to religion, he had nothing against religious people in general, and certainly nothing against Jews in particular. He couldn’t fathom why someone who’d gone through the things Myna had would ever tell such jokes. More amazing was the fact that Leon, who’d apparently tolerated nothing in the way of either rudeness or a sense-of-humor in raising my mom, never objected to these outrages.

Apparently, the night Myna met Leon (they both chaperoned the blind date my parents went on as freshmen at Pitt), she watched him puff on his cigar after picking them up in his broken down Dodge and asked him how many Jews fit in the new Mercedes-Benz.

506 was the answer.

Six in the seats.

And five hundred in the ashtray.

Leon evidently didn’t laugh, or even smile, but he also didn’t spend the rest of the date browbeating Dad into never asking his daughter out again—something he did to every other date she’d ever had, not that he’d permitted many.

My parents were mortified from the start that night, but also falling in love.

None of my classmates responded to Myna’s query about wandering Jews. This was worse than a boring story. Tests were for real school.

Tziporah surveyed us, angrily. I wondered if I should throw myself on the floor and simulate a seizure. Anything.

“Jonathan,” Tziporah said. “I’m sure you can answer the question.”

“Jonathan,” Tziporah said. “I’m sure you can answer the question.”

I couldn’t, and despite years of instruction, I was willing to bet most of the rest of the class couldn’t either, but that was beside the point. “But she doesn’t actually want the real—” I started to protest.

“Jonathan, your grandmother has taken the time to come to our class. You’ve been nothing but rude. Pretending to be ignorant impresses no one.”

Absolutely wrong! I wanted to shout. And I wasn’t pretending!

“Oh, he knows all right,” Myna said. She was smiling ear- to-ear.

The whole class was looking at me. Now I was defying my teacher and my own grandmother. Finally, I mumbled something unintelligible under my breath.

“What, Jonathan?” Tziporah asked.

Myna kindly clarified. “He said the Jews wander in the desert for forty years because someone drops a shekel!”

Everyone gaped at me. Then they all turned as one to see how Tziporah was going to react.

React she did.

My teacher rose from her chair like a column of black, smoking death. She flew at me in a fulminating rage, then dragged me to the hall by my right armpit, which I assumed was some secret Israeli army maneuver. I caught a glimpse of a genuinely surprised look on Myna’s face as I was manhandled past her.

In the hall, Tziporah berated me for fifteen minutes about my blatant disrespect for my grandmother, not to mention six million murdered brothers and sisters of mine, for my clear manifestation of something called the “Self-hating Jew Syndrome,” and for trading my obvious academic potential for a jester’s cap. I had no choice but to tell her Myna was not actually quizzing the class on its level of biblical scholarship, but that only made her skull appear dangerously close to exploding.

A burst of laughter came from the classroom, snapping Tziporah out of her conniption. She shoved me back into the room just as Myna was thanking my classmates for their attention.

I threw myself into my seat with a huff.

“You’ve been wonderful children,” Myna cooed. “I want you to remember just one thing—one thing only. Adolf is alive. He is hiding in every non-Jew. Scratch deep enough and you’ll find him. So don’t scratch, okay? Get a good ointment and slather it all over the goyim. No one likes the rash.”

The class giggled. Tziporah looked confused. She managed some polite clapping that was a signal for us to do the same. Myna bowed slightly and flashed me a wink.

Then she left.

When the door closed behind her, Amy Baumgardner said, “She’s cool.”

Tziporah, somewhat regrouped, asked the class to share what they’d learned.

Andy Katz said, “That Jon’s lucky he doesn’t have three heads and six arms.”

********

reprinted with permission. Fun and Games is available on Amazon, Barnes and Noble, the Library Tales Publishing website and elsewhere. For more about David Michael Slater, www.davidmichaelslater.com.

********

[…] sadistic bullies, but if you went to high school you’ll relate. Read our exclusive excerpt here, and watch for this book to be republished in 2015, hopefully this time with the PR it […]