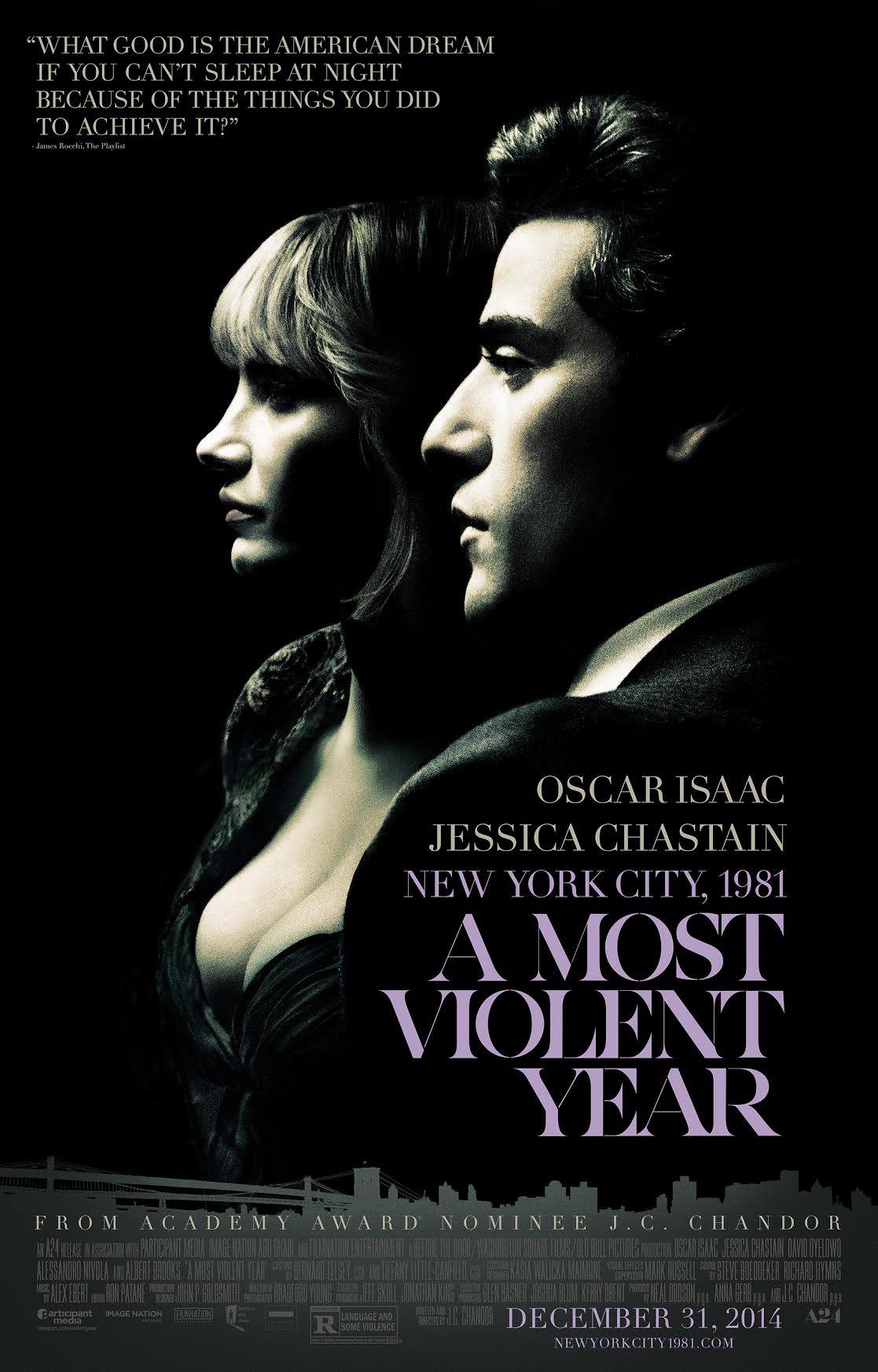

It’s the winter of 1981 in New York City and somebody is fucking with Abel Morales (Oscar Isaac, Inside Llewyn Davis). All the man wants to do is see through the completion of a land deal that will allow him to expand his small heating-oil distribution company. He’s bet it all on this deal, wiping out his savings and hoping for a bank loan that has yet to finalize. As written and realized by director J. C. Chandor (Margin Call, All Is Lost) Abel is, at his core, one of those quintessential American characters: a first generation immigrant risking everything for a shot at the brass ring.

But again, somebody is fucking with Abel Morales, namely in the form of armed men sent to hijack his trucks and strip them of fuel. In A Most Violent Year’s gripping opening sequence, Chandor cross-cuts between Morales and his lawyer (an always-welcome, but frustratingly unremarkable Albert Brooks) as they finalize the deposit on the land while Julian (Elyes Gabel), a driver for Abel’s business is carjacked and severely beaten: A juxtaposition that embodies Abel’s philosophy of risking everything at one’s weakest moment.

But again, somebody is fucking with Abel Morales, namely in the form of armed men sent to hijack his trucks and strip them of fuel. In A Most Violent Year’s gripping opening sequence, Chandor cross-cuts between Morales and his lawyer (an always-welcome, but frustratingly unremarkable Albert Brooks) as they finalize the deposit on the land while Julian (Elyes Gabel), a driver for Abel’s business is carjacked and severely beaten: A juxtaposition that embodies Abel’s philosophy of risking everything at one’s weakest moment.

Despite his attempts to maintain an aura of strength, friend and foe alike can smell Abel’s vulnerability; A tenacious DA (Selma’s David Oyelowo) tasked with investigating the heating-oil industry has chosen to file charges against Abel, solely to make an example out of him; A union rep demands Abel’s drivers be armed to defend themselves against attacks, something Abel cannot abide, believing it would heighten an already volatile situation: Even Abel’s wife, Anna, (Jessica Chastain) pressures him to ask her gangster father for help.

But in the midst of all the bullshit piling up around him… Abel plays it cool. Calm. Reserved. Deliberate. For what is ostensibly a crime film (and A Most Violent Year is a crime film) we are given a protagonist who steadfastly refuses to do anything criminal. Sure, he’ll take the shortcuts and fudge the books a bit, but in an industry where, as the DA says, “everyone is stealing from each other,” Abel might as well be a saint.

Here, then, the crux of the film: Can Abel adhere to his moral code while everyone and everything keeps pushing him to break it? It’s a compelling conflict, especially as American crime films typically posit that corruption is the only path to success. But Chandor, whose filmography reveals a fascination with how men respond to crises, flips the premise, wondering what the struggles and implications are of a good man navigating a corrupt system. Does the American dream still have room for a man like Abel or is he doomed to an apocalyptic level failure?

Chandor’s choice of setting, 1981 New York City, hints at what possible future may await his characters. The early 80s notoriously saw the city begin to slip into a decade of social freefall, violent crime and urban blight, while a shitty b-movie actor-turned-President championed “fuck you, got mine” as a pillar of American identity. A storm is coming and Abel believes the only way he can weather it is through thoughtful, deliberately ethical choices and a head down, dogged determination to keep pushing forward.

Without an actor as engaging as Isaac, it’s unlikely A Most Violent Year could enthrall as much as it does. With a character heavily defined by clockwork-like cognition and mental strategizing – not a showy role by any means – Isaac still manages to endow Abel with humanizing warmth and vulnerability. With a protagonist so well realized, the rest of the cast feels slightly perfunctory by extension, existing either to push Abel away from his dogged adherence to the righteous path, or to serve as philosophical counterpoints.

One such counterpoint is Chastain as Abel’s wife, Anna – a persistent advocate for the most brute force of solutions. Unfortunately hers is a last-act-of-Goodfellas-Lorraine-Bracco performance in a role that demands Lady Macbeth-levels of menace. Albert Brooks – playing, perhaps, the most well adjusted character in his entire filmography – acquits himself admirably as Abel’s lawyer, but unfortunately doesn’t have much room to dazzle in what is a fairly straightforward role. Instead, it’s Oyelowo as the District Attorney eager to make a name for himself and Gabel, as Julian, the driver who dreams of wealth but seems unable to achieve it, who break through as most memorable.

One such counterpoint is Chastain as Abel’s wife, Anna – a persistent advocate for the most brute force of solutions. Unfortunately hers is a last-act-of-Goodfellas-Lorraine-Bracco performance in a role that demands Lady Macbeth-levels of menace. Albert Brooks – playing, perhaps, the most well adjusted character in his entire filmography – acquits himself admirably as Abel’s lawyer, but unfortunately doesn’t have much room to dazzle in what is a fairly straightforward role. Instead, it’s Oyelowo as the District Attorney eager to make a name for himself and Gabel, as Julian, the driver who dreams of wealth but seems unable to achieve it, who break through as most memorable.

Ultimately, though, it’s DP Bradford Young’s beautiful cinematography that deserves second billing after Isaac. Young bathes his exteriors in the pale yellow light of a low winter sun, evoking the sense that we’re never that far off from total darkness. It’s a terrifying feeling that everything might be truly fucked. Chandor’s assured direction also underscores that same sense of creeping dread and impending calamity. Skillfully employing anamorphic widescreen compositions, Chandor often uses long shots to frame Isaac in center frame, the negative space reminding us of the world bearing down on him.

Chandor’s greatest accomplishment as this story’s teller comes in his ardent refusal to canonize Abel. Though Abel’s cherished morality precludes him from greed, selfishness and violence, it still leaves victims in its wake. In a relationship that recalls that of Cain and Abel, collateral damage comes in the form of driver Julian, who confronts his second hijacking attempt with armed resistance leading to a gunbattle and escape that threatens to completely derail Abel’s land deal. How Abel handles Julian defines his the underpinnings of his philosophy: do the right thing, because it’s usually what’s best business.

While crama dramas as stealth critiques of capitalism are par for the course, they’re often couched within a winking-irony that at once disparages material wealth while at the same time titillating audiences with lustful images of conspicuous consumption. Scarface may be a monster, but the dude has a tiger and a mountain of cocaine, don’t even pretend you don’t want it. The critique in A Most Violent Year is more explicit, especially with one brutal act of violence late in the film that throws Abel’s entire philosophy into stark relief. Abel’s code is how he sleeps at night. But, in the end, we learn that it’s ultimately a distraction, a whitewash of the fact that no matter how you play the game, someone always has to lose.

Leave a Reply