To be honest, the less you know about Samuel Sattin‘s novel, The Silent End, the better.

Here’s all you need: Three teenagers discover a dying monster in the woods of Mossglow, their small Pacific Northwest town. In doing so, the trio find themselves plunged into a nightmare world of impossible creatures, infernal machines, and one very strange hat.

That’s all you get. The rest of the book is – for your own sake – best left discovered in situ.

That’s because, ultimately, The Silent End isn’t so much a story about what as it is about why. Yes, the narrative is full of Lindelof-ian twists, and Lynch-ian menace, but what truly sets The Silent End apart is Sattin’s fully realized characters, and the care with which he explores and expands upon their relationships with one another: romantic, platonic, and parental. Characters are driven, first and foremost, by friendships and enmities which breathe life into a story about monsters, murder, and the indignities of high school.

At first, horror might seem a strange fit for this sort of literary relationship spelunking. To Sattin, however, it’s a natural match. “Horror, to me, is a pretty ruthless genre, in the sense that the goal is to cause unease.” he explained when I asked him about layering The Silent End‘s complex friendships atop a framework built for scares: “Friendship is pretty scary stuff as it is, but if you’re a kid, particularly if you’re a teenager, it’s terrifying. Not necessarily in the way it begins, but in the way that it grows, and changes. If you think about it, your head is filled with gray matter in high school. You have no idea who you are. And then, as you grow towards the end of your teens, you start to gain a sense of self. Sometimes friendship can survive that mutation. But other times, it can’t. And I think that maybe that’s the part that melds so well with horror.”

At first, horror might seem a strange fit for this sort of literary relationship spelunking. To Sattin, however, it’s a natural match. “Horror, to me, is a pretty ruthless genre, in the sense that the goal is to cause unease.” he explained when I asked him about layering The Silent End‘s complex friendships atop a framework built for scares: “Friendship is pretty scary stuff as it is, but if you’re a kid, particularly if you’re a teenager, it’s terrifying. Not necessarily in the way it begins, but in the way that it grows, and changes. If you think about it, your head is filled with gray matter in high school. You have no idea who you are. And then, as you grow towards the end of your teens, you start to gain a sense of self. Sometimes friendship can survive that mutation. But other times, it can’t. And I think that maybe that’s the part that melds so well with horror.”

Melding is a big part of The Silent End. Like his debut novel, League of Somebodies, The Silent End finds Sattin mixing and matching genres, styles, and – in the case of the story’s monsters – body parts. You’d be hard pressed to find creatures like The Silent End‘s, each comprised of otherworldly flesh, bound in a cocoon of organic ichor and technological detritus: A broken blender here, a cracked lightbulb there, metals and plastics and flesh all pureed together and molded into impossible forms.

“I’m really interested in body horror,” says Sattin. “In the way we’re made uncomfortable by normal things when they’re taken out of context. Picasso did this with women, with nudes. He’d rearrange parts of the body, restructure them, until they were rendered into something that made viewers uncomfortable, and contemplative. David Cronenberg is certainly an influence here, so is John Carpenter’s The Thing. So, believe it or not, is Hayao Miyazaki.”

In that sense, Sattin’s creations are terrifying, not only because of their monstrous actions, but by virtue of their very elemental nature. They are, as we come to learn, composite nightmares, and stand out as some of the more unique creations in modern horror.

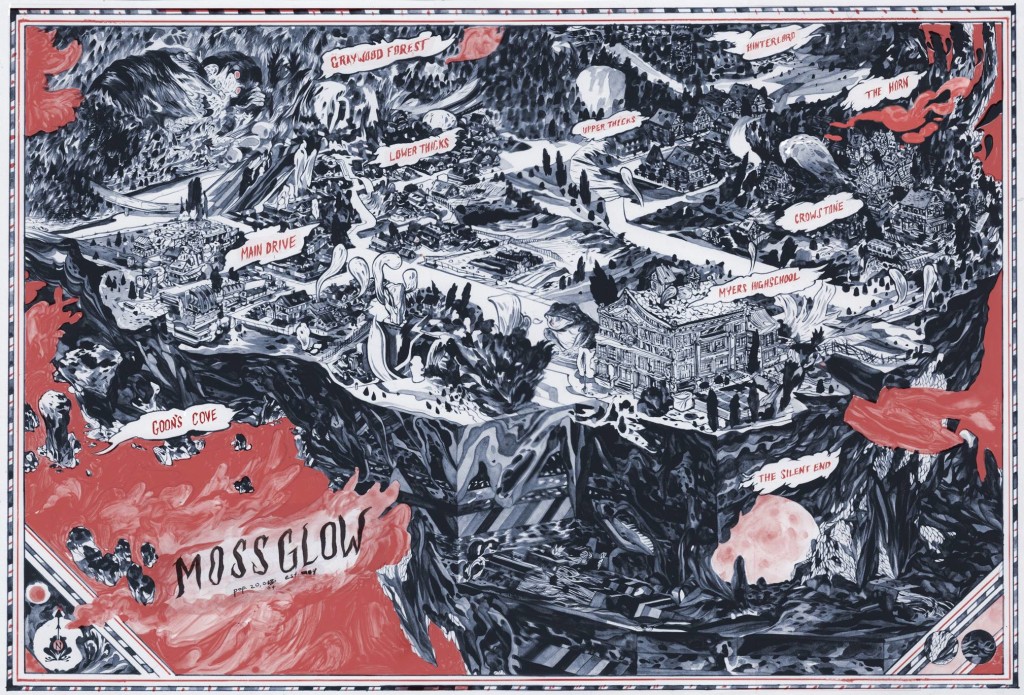

Mossglow illustration by Jacob Magraw-Mickelson

Equally unique is the story’s setting of Mossglow, a sleepy, isolated town in the Pacific Northwest that seethes with unsettling menage, while remaining grounded and recognizably real. The care with which Sattin establishes a sense of “place” is one of The Silent End‘s strongest suit, with Mossglow worthy of joining the ranks of iconically established locales such as Buffy Summers’ Sunnydale and LOST’s mysterious Island. And while Sattin readily acknowledges David Lynch as an influence on the town’s conception, he credits an altogether different genre of fantasy with helping turn Mossglow from idea to full-fledged environment, explaining:

“I was also inspired by my love of role-playing games, particularly as a kid, and the maps I found in fantasy books. My friends and I used to create our own worlds, and then play games with them, Dungeons and Dragons, mostly. I always found it funny how, when you start drawing a map, you start having to justify why you’re doing so. What’s the purpose of this place? Why does it exist? In some ways, and I know this sounds corny, because it is, Mossglow became what it is in that way. I had to give it a reason to exist.”

Sattin has perhaps put a bit of himself into the story’s hero, Eberstark, as well. “I grew up in a smallish suburban zone outside of Denver, with wide open prairies, reservoirs, and a fairly insubstantial population of Jews. I mean, we had them! I went to Hebrew school, got my Bar Mitzvah, did the Israel thing, etc. But it’s not the same as growing up in a place where Jews have a little more of a presence […] In some ways, Eberstark understands this. He’s Jewish, but he’s careful about making it a focal point of his identity in conversations with others. Because he lives in a smaller place. And smaller places can be hostile. But in my opinion, he’s still a very Jewish character. His paranoia, his self-debasement, his want for bigger things and tendency towards over-analysis? If you read between the lines, it’s plain to see.”

At its core, though, and without giving too much plot away, The Silent End is really a story about men and women, and the various dynamics that exist between these two sexes. It dwells on love and loss, and explores way those can shape, inspire, and trap a person. For Sattin, this is in some ways inspired by his own experience: “A lot of it for me is oddly personal,” he tells me. “Though not in any conscious fashion. I don’t think I knew that I was writing a story about my family, and notably the loss of my mother six years back, until after it was all wrapped up and getting sent out to the publisher.”

At its core, though, and without giving too much plot away, The Silent End is really a story about men and women, and the various dynamics that exist between these two sexes. It dwells on love and loss, and explores way those can shape, inspire, and trap a person. For Sattin, this is in some ways inspired by his own experience: “A lot of it for me is oddly personal,” he tells me. “Though not in any conscious fashion. I don’t think I knew that I was writing a story about my family, and notably the loss of my mother six years back, until after it was all wrapped up and getting sent out to the publisher.”

Sattin also spends much of the book toying with the male-female dynamic in order to upend what he feels is a problematic literary crutch. He explains: “I think it’s probably plain to see that I’m really kind of fed up with tropes, mostly the one that champions women as vessels for male self-emancipation. It’s not only that I think it’s offensive, really, as much as I think it’s the worst form of wish-fulfillment. It’s a fantasy, this idea of women being objects of personal advancement for men. A stupid fantasy. And in horror, as in fiction across the board, this mentality is rampant.”

Ultimately, if there’s a fault with The Silent End, it’s the dizzying dexterity with which the story flits from one genre to another, which might leave readers scratching their heads as they wait for a beat that never comes, the author having subverted, subsumed, or simply abandoned the expected convention entirely.

Still, for those who stick with Sattin and his characters, The Silent End offers a rare thrill in that glutted field of mediocre young adult fiction, horror, and fantasy: A story which transcends genre and narrative trappings, leaving you guessing until the very end, and wanting more, long after that.

*****

For more visit SamuelSattin.com

The Silent End is available now, from Ragnarok Publications.

Leave a Reply