Let Jewdar be upfront about this—What Our Fathers Did: A Nazi Legacy was not our cup of tea, but that doesn’t mean it isn’t worth watching. And we also want to make clear that part of our objections have less to do with the film, perhaps, than with our own feelings about the subject, which is not, let’s be clear, the Final Solution, or Nazism, but fathers and sons.

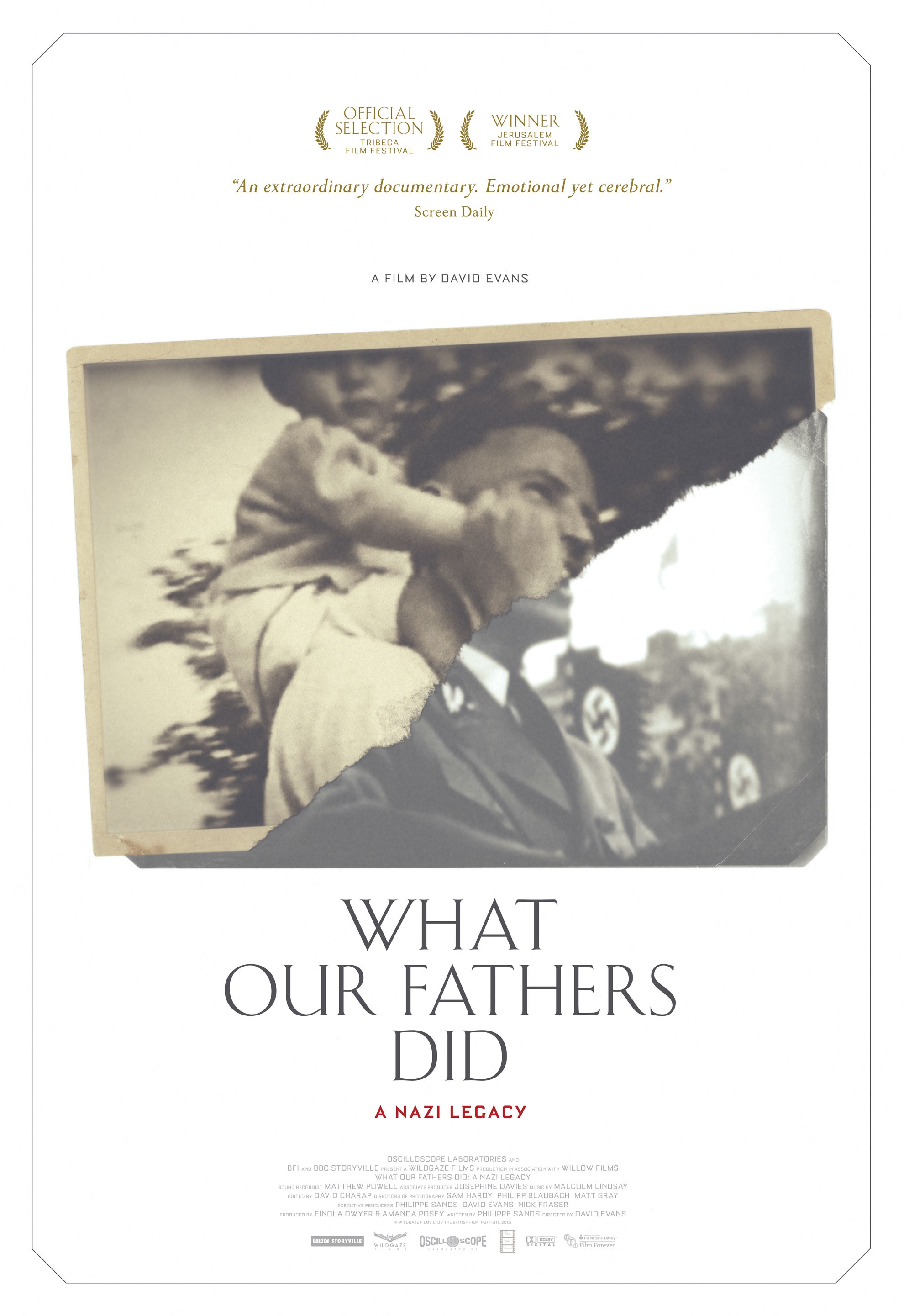

The documentary features discussions between Human Rights Lawyer Phillipe Sands (who sounds a lot like Severus Snape) and the sons of Hans Frank and Otto von Wachter, the Governor-General of Nazi-occupied Poland and Governor of Galicia, respectively. It is not a documentary about history–we learn very little about the war or the actions of the individuals involved–but it does not pretend to be. It is a film about memory and denial, most precisely, the degree to which Wachter’s son Horst (named after Horst Wessel), despite his efforts to connect to Jews personally, refuses to recognize the role his father played both in implementing the Final Solution and the dispossession of Galician Poles. To that end, much of the film revolves around efforts by Sands and Frank’s son, Nicholas (who most certainly recognizes his father for the monster he was) to get Horst to stop acting like a Teutonic Bartleby the Scrivener.

“Do you believe your father helped commit mass murder?”

“I’d prefer not to.”

On a personal sense, as noted above, it’s not really Jewdar’s thing. We don’t really care what Horst von Wachter thinks about dear old dad; he’s not denying the Holocaust, just his father’s culpability. Dishonest, to be sure, but it strikes us as ultimately no different from the personal dishonesty that afflicts anyone whose beloved parent turns out to have fallen short of one’s image. At that point, von Wachter could be talking about a father who turned out to have been cheating on his mother, or committing tax fraud–the crime itself is less significant than the son’s response.

Shoah was an incredibly powerful movie because Claude Lanzmann gaves us the perpetrators and witnesses victims in their own words, gave us a window into the Final Solution we wouldn’t otherwise have. Such a movie, of course, can never be made again, and so instead of a movie about the Final Solution, we are left with a film–fine, we suppose, for what it is–about the generation after. If you are interested in the psychology of families, this movie might be right up your alley, which is why we said from the start it may be worth watching. There is at times an exquisite tension in the questioning of Wachter by Sands, who is, after all, an accomplished attorney, and there are moments that play out like a courtroom drama. But to Jewdar, the question of personal memory of the Final Solution and its perpetration are far less important and interesting than the question of collective memories of the same.

At one point, Sands and Wachter travel to Ukraine, where a commemoration is being held for the Waffen-SS Division Galicia that the latter’s father had helped establish. It is a remarkable tableaux, complete with admirers bedecked in an assortment of German military equipment for whom Otto von Wachter was a patron and benefactor of the Ukrainian nationalist project. Short shrift is given to the sentiments of those in attendance, and how they remember not only the Germans, but their erstwhile Jewish and Polish neighbors, and the ways in which their fight for independence intersected with the larger conflicts raging around them. If somebody wants to pick up their story where Sands left off, that’s a film Jewdar would want to see.

Leave a Reply