In 1967, as nearly half a million American troops fought in Vietnam, MIT linguistics professor Noam Chomsky wrote an essay for the New York Review of Books that derided his fellow intellectuals for standing by silently in the face of such an abhorrent war. Literary critic George Steiner wrote a letter of response that was heavy with anguish: “The intellectual is responsible. What then shall he do?” Steiner asked, wondering if he should help his draft-age students escape to Canada, or if he himself should run for the border. Chomsky replied with measured gravity, saying that he thought it best for the “anti-war American intellectual to stay here and oppose the government, in as outspoken a way as he can, inside the country, and within the universities that have accepted a large measure of complicity in war and repression.” It was a call to action that Chomsky himself has lived by unwaveringly ever since.

Prophet, blasphemer, genius, traitor—Noam Chomsky has been called all four. In linguistics, his significance is indisputable. His 1957 book, Syntactic Structures, revolutionized the field with its thesis—now widely accepted—that all human language shares a universal grammatical structure. In politics, his activities have been more controversial, as he has spent the better part of the past 40 years excoriating the United States government for a wide variety of crimes. In numerous books on U.S. foreign policy, and in speeches around the world, he has pilloried America for its intervention in Central America in the 80s, its collusion with Israel against the Palestinians, its support of despots from Indonesia to Chile and its entry into both wars with Iraq.

Chomsky’s indictments can be enough to make you rend your garments in despair. His critics are many, their attacks ranging from the ad hominem (he’s frequently labeled anti-American and anti-Semitic) to the sound (such as the charge that his arguments are cloaked in deceptive sophistry). Still, he has near cult-like status among progressives and workers worldwide, and rock star cred with the kids—how many other scholars, after all, can say they’ve released a split seven-inch with Bad Religion?

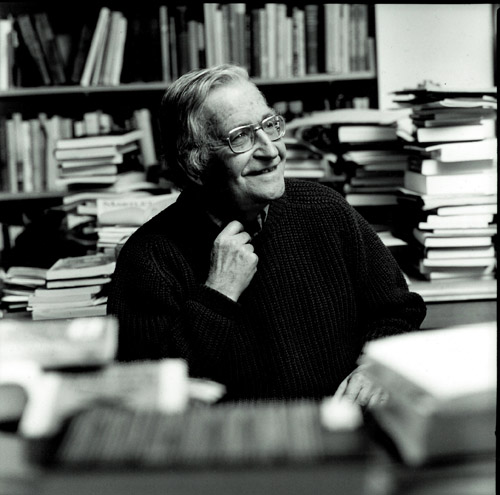

Going to see Chomsky in his office at MIT is like visiting a sort of lefty Yoda. He is a smiling and wrinkled old anarchist Jew who sits ensconced in his cave of books, quietly dispensing his philosophy with the exactitude and ruthlessness of a precision-guided missile.

Heeb: You’ve been maligned by other Jews for a long time because of your views on Israel and Palestine. The Anti-Defamation League has a file of hundreds of pages on you. Alan Dershowitz has called you bigoted and shameful. Obviously, you’ve been challenged from many directions for your ideas, but I wonder how the particular arrow of being called a self-hating Jew feels?

Chomsky: Well, I had a good Jewish education, so I know the origin of the “self-hating Jew” notion. It goes straight back to the Bible. King Ahab, who was the epitome of evil in the Bible, condemned the prophet Elijah as a hater of Israel. Why? Because King Ahab identified himself with the people—a typical totalitarian tactic. Ahab is Israel, Elijah and other prophets were giving geopolitical criticism, calling for justice and freedom, so therefore they were haters of Israel—or “self-hating Jews” in the modern terminology.

In the Jewish tradition, the ADL identifies itself with King Ahab if it really believes that people calling for freedom and justice and giving critical geopolitical analysis are haters of Israel. The modern totalitarian traditions take the same view—Stalin was very much like King Ahab. People who dissented in Russia were condemned as “haters of Russia.” Being anti-Soviet was the worst crime. And it makes sense, from their point of view, that if you identify the system of power with the country, people, culture and so on, then anyone else who speaks for the country, people and culture is a hater of the state. That is the ADL position. They have a noble tradition going straight back to the worst character in the Bible, taking the same view that he took of critics. Anyone with a Jewish education should understand that.

How do you respond to Jews—even progressive Jews who are critical of the Israeli government’s policies and actions—who think that however safe we may feel in the Diaspora, the embers of anti-Semitism will forever smolder somewhere in the world, and Israel is therefore necessary to insure against another Holocaust?

A Jewish state doesn’t prevent a Holocaust. In fact, the place where Jews are most in danger happens to be in Israel. And what they call “anti-Semitism” arising elsewhere in the world is usually a reflection of antagonism to the policies of the state of Israel. So it has nothing to do with preventing another Holocaust.

Now, the question about a Jewish state is something quite different. I was a Zionist youth activist in the 1940s, and I was part of the Zionist movement that thought it was a mistake to establish a Jewish state. That was a Zionist movement at the time. In fact, those who don’t want to go back to King Ahab to understand their tradition can go back to 1942. 1942 was the first time in which a Zionist organization—the American Zionist Organization—officially accepted the concept of a Jewish state. Before that, it had been talked about but it wasn’t officially accepted. In 1942 at the Baltimore Conference, the American Zionist Organization officially committed itself to a Jewish state, and shortly afterwards, the Jewish community did so as well. But before that, it was seen as only one possible way of establishing a national home. I was part of the Zionist movement that thought that was a mistake.

Why, exactly?

For the same reason that I don’t think an Islamic republic of Pakistan is a good idea, and I don’t think a Christian state, if that’s what the U.S. were, would be a good idea. States should be the states of their citizens, not the state of some privileged group of citizens. Now, if this is purely symbolic, then it doesn’t matter very much. Okay, so here you don’t have stores open on Sunday or something. That is symbolic. Nobody cares. On the other hand, if it goes beyond symbolism it can be very serious. And in Israel it goes way beyond symbolism, by a variety of administrative and legal provisions. It ends up that about 90% of the land is reserved for people of Jewish race, religion and origin. If 90% of the land in the United States were reserved for people of white, Christian race, religion and origin, I’d be opposed. So would the ADL. We should accept universal values.

Once Israel was established in 1948—though in my view it was a mistake—once it was established, it had all the rights of any state in the international system, no more, no less. And that has been my position ever since. I think it ought to change, and most of my friends in Israel agree. In fact, even the courts have called for some changes in this. But to say this has anything to do with the Holocaust is just in an insult to the memory of the victims. I mean, you can’t think of a worse insult to the memory of the victims of the Holocaust then to conjure them up as a justification for your own oppressive practices. That’s just disgraceful.

[…] Jew,” although he cites not the Talmud but the Tanakh. Here is an example from an interview in the […]