[Editor’s Note: We at Heeb are devastated by the news of Joan River’s death. Joan was a comedic force of nature, and one of the greatest entertainers in the history of the world. We can think of no better way to celebrate Joan Rivers than to share Jay Ruttenberg’s 2007 profile – perhaps the definitive profile – of Joan’s life and work. She will be missed. The world is a less funny place without her.]

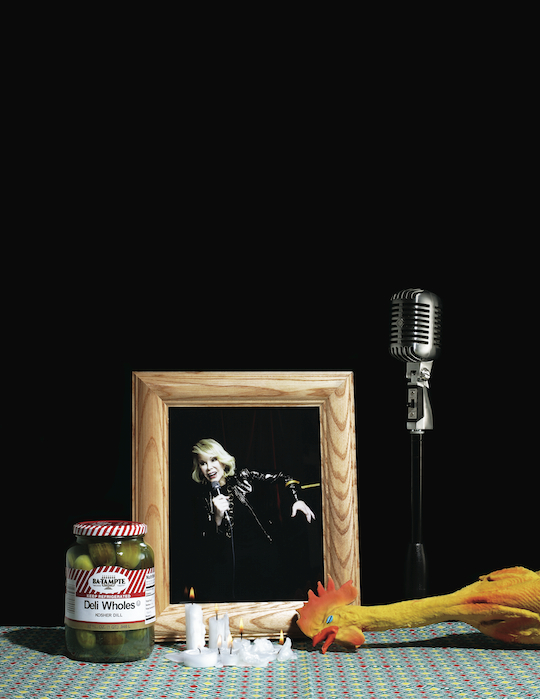

My favorite Joan Rivers joke concerns her daughter. Melissa calls her mother for advice. Playboy has offered her $500,000 to pose nude from the waist up, and she is unsure whether she should accept the magazine’s offer. Joan tells her daughter to do whatever makes her comfortable and Melissa instructs _Playboy_ to take a hike. At this point in the joke, Rivers stares into her audience as if searching for a lifeboat. She raises her arms skyward, widens her wicked eyes, hurls her pint-sized frame against the stage’s piano. “Can you believe the nerve of that bitch?” Rivers roars. “She’s been divorced for three years and I’m still paying off her wedding! I’m 73 fucking years old, standing on a red carpet saying, “Who are you wearing? Who are you?’ $500,000, and she turns it down?!? What should you do? Pull down your pants and show them the pussy!”

And there, in a gloriously vulgar nutshell, is Rivers’ stage persona—which she has perfected in recent years, not as a big-wheel celebrity, but rather as a stand-up comedian, improbably reborn, playing to a strange New York cult of Jews and queens. She is dirty, greedy, tacky and acerbic, uttering words and beliefs that we are instructed to abandon long before old age. Most extraordinary is Rivers’ knee-jerk nihilism—her eagerness to pull down her daughter’s pants for money and a laugh. And does anything else in life matter? To Joan, the cartoon embodiment of yenta callousness, the answer is a defiant no. The only question is which reward she values more.

Many people don’t even think of Rivers as a comedian, but rather as a red carpet bitch, lacerating the famous with her acid tongue, or as a QVC diva, pedaling gaudy jewelry to suburban women. Yet before she inhabited either of those roles—and even before she was a Tonight Show mainstay, late-night calamity, owner of the phrase “Can we talk?”, mother, widow, grandmother and plastic surgery addict—she was a stand-up comedian in downtown New York. As with many of her pals from that time, Rivers would springboard to a higher pay scale and level of fame, reminiscing about her scrappy days playing the small rooms. But unlike those colleagues, in an astonishing twist of showbiz chutzpah, Rivers chose to return.

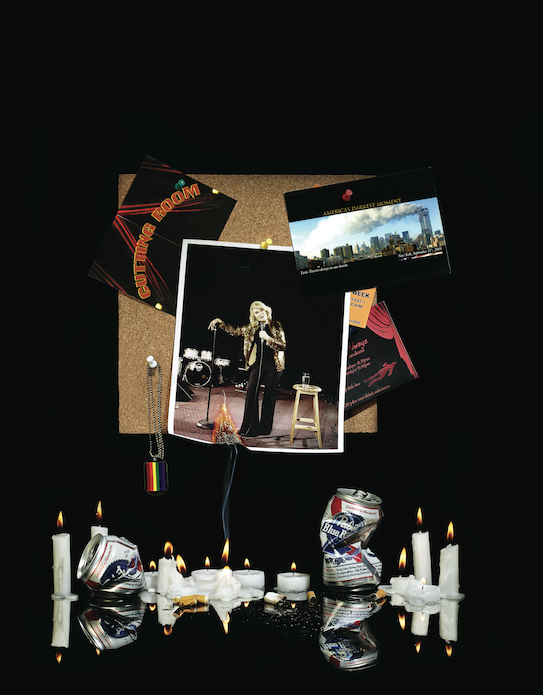

It was a little over four years ago when Rivers went back to playing small New York City clubs. She was well into old-ladyhood and had moved beyond the hardships that had nearly wrecked her in the ’80s: the cancellation of her late-night show and her husband’s suicide. She booked a performance at Fez Under Time Café, a snug cabaret space situated beneath a Moroccan restaurant in downtown Manhattan. A few shows begat a weekly residency, which became a more-or-less permanent residency until Fez was shuttered, at which point Rivers, without skipping a beat, moved her gig a few blocks north to the Cutting Room—an even smaller venue. Unless she is out of town, Rivers performs there every Wednesday night. The shows cost $25 to attend, and her entire fee is donated to charity. The comic’s Manhattan performances deviate from her road act, which is geared toward larger audiences and is thus more structured. “They’re paying more, and it’s a concert thing,” Rivers says, “so I give them easier stuff. They don’t have to decide, ‘Can I laugh at this?’ Whereas at the Cutting Room, it’s all about making decisions.”

The fundamental decision demanded of Joan’s audience is whether it’s acceptable to throw one’s morals to the wind. Her act celebrates all that is wrong: stealing, avarice, wearing fur, marrying for money, even voting Republican. (She claims to have defected from the Democratic Party when Amy Carter wore glasses at her own wedding.) When she disparages Anne Frank as a “whiner,” her tone contains no cheap irony, which renders her stance more mysterious and infinitely funnier. The Holocaust itself, she informs a table of noshing Jews, occurred after “nobody heard the screams from the oven since they were all stuffing their mouths.” She professes hatred for the unattractive (“If you’re ugly, you should kill yourself”), the handicapped (“It’s God’s way of saying don’t leave the house and steal Joan’s parking spot”) and the man in the audience who said he didn’t watch her at the Oscars (she can be strangely thin-skinned). God’s Love We Deliver, a service that brings meals to AIDS patients and is a primary recipient of her show’s profits, is disparaged accordingly. Because of advances in medicine, the AIDS patients she has been helping are not dying. “I’ve been delivering dinner to the same fucking asshole for four years,” she cries from the stage, “and he’s getting fat!”

Some nights, Joan is funnier than others, but a distinctive air of unpredictability always permeates. “I think she likes these shows so much because she’s flying without a net,” says Chip Duckett, who, as producer of her show at the Fez and now Cutting Room, has seen her act a hundred times over. “It’s an exciting feeling to be in that audience, to see a comedy legend telling filthy jokes to a room of 100 people. That kind of thing is the reason I moved to New York—that’s what I hoped to find here. And she really considers the work she’s doing there to be important. She’d probably implode if she _couldn’t_ do it.”

A cheery middle-aged man who I take to be Joan’s butler—he wears an apron, relieves me of my coat and is British—enters Rivers’ library and deftly navigates his way around the two small dogs sprawled at her feet. He places a coffee-related drink before the comedian and a silver platter laden with apricot rugelach by me, then leaves with the unassuming grace of a ninja. Rivers plucks a rugelach from the tray, takes a bite and feeds the rest to her hounds. “Oh yes,” she says to the dogs. “We love rugelach, don’t we?” Her baby talk is deep and scratchy.

Joan lives in the penthouse of an old limestone building in the lower regions of Manhattan’s Upper East Side, seconds from the park and, perhaps of greater importance, Bergdorf Goodman. The building was designed by Horace Trumbauer, architect of the gilded age; Ernest Hemingway once lived there. It has all the ostentation you would expect: an old-fashioned elevator with its own operator, ornate walls emblazoned with the type of gold trim traditionally favored by European monarchs, a book-filled library with a blazing fireplace and a stray piece of mink flopped across the sofa. Yet her duplex has a bright, loud vibe not in keeping with its grandeur. Phones ring incessantly, assistants converse in the background, her dogs race about and the help kibitz with their employer about their mutual affinity for _The Sarah Silverman Program_. On her sofa lies a needlepoint pillow reading, “I need a man to spoil me or I don’t need a man at all.”

Joan lives in the penthouse of an old limestone building in the lower regions of Manhattan’s Upper East Side, seconds from the park and, perhaps of greater importance, Bergdorf Goodman. The building was designed by Horace Trumbauer, architect of the gilded age; Ernest Hemingway once lived there. It has all the ostentation you would expect: an old-fashioned elevator with its own operator, ornate walls emblazoned with the type of gold trim traditionally favored by European monarchs, a book-filled library with a blazing fireplace and a stray piece of mink flopped across the sofa. Yet her duplex has a bright, loud vibe not in keeping with its grandeur. Phones ring incessantly, assistants converse in the background, her dogs race about and the help kibitz with their employer about their mutual affinity for _The Sarah Silverman Program_. On her sofa lies a needlepoint pillow reading, “I need a man to spoil me or I don’t need a man at all.”

Rivers has been busy. The previous evening, she flew into New York from a road gig and went straight from the airport to the Cutting Room. The comic was a fright from the plane, so her hairdresser met her at the club and fixed her up in the dingy hallway backstage. Hours later, she woke up and appeared on Martha Stewart Living, which she claims to love going

on “because I take all her hors d’oeuvres home.” Without changing from the puffy red outfit she wore on Martha, Rivers retreated to her office and wrote real estate jokes in preparation for a corporate gig that evening for The Corcoran Group. When Joan says “Corcoran Group,” she employs the mocking tone one might use to send up the Prince of Wales. “They said to me, “We don’t want anything blue,'” Rivers rasps. “I love when they use the term ‘blue,’ because that tells you they’re over 35. I said, ‘Have you got the wrong chick.'”

She was disappointed with her previous night’s Cutting Room performance. “I had just come off a show that was so spectacular, and the audience wasn’t as good as the night before,” she says. “I mean, they didn’t know they weren’t good. They thought they had a terrific show. But I walked off and thought, ‘Achhh.'” Rivers starts cackling, as she does whenever she is about to say something inappropriate. “I started the night talking about 9/11,” she says, still laughing. “I hadn’t even warmed them up. That was my first subject. It was like, ‘Hello, good evening—so, who do you wish had died?’ There was a lot of gasping.”

The bit Rivers is referring to is among her most vicious. It finds her lowering her voice to a conspiratorial whisper and asking her crowd, “If you knew what was going to happen on September 11th, who would you invite to breakfast at the World Trade Center? ‘Eggs benedict…Windows on the World… It’ll be our make-up brunch!'” Week in and week out, the funniest part of the joke isn’t the punch line so much as Rivers’ indignation when the audience falls silent. “Oh look at this room!” she’ll yell. “What are you, a bunch of Christians? You’re telling me there aren’t people you want to see dead? I could give you a list a mile long!”

On a good night, somebody might boo; on a great night, a person will walk out. “Somebody should be upset,” Rivers contends. “If you’re a comedian and people think, ‘Oh, she’s so nice,’ then what are you doing? You’re not contributing anything. Comedians are there to shake people up and make them face the truth. Because if you face the truth, you can get through anything.”

Rivers grew up in one of those upwardly mobile Jewish families that fled Brooklyn for suburbia, in this case Larchmont, New York. Before she adopted a stage name, she was Joan Molinsky. Her family belonged to a country club—her father was a doctor—but there was no synagogue in the city, so religious services were held in the firehouse. When Joan’s sister graduated from Columbia Law School, she was the youngest woman ever to earn a degree from the school. “We were very, very, very, very, very smart,” Rivers says. In 1954, Joan left Barnard with a degree in English and a Phi Beta Kappa pin. She was eager to please her parents. “I did what good Jewish girls do,” Rivers says. “I got the big ring, I got married—and I was miserable. I was so unhappy. It lasted six months.”

Rivers decided to become an actress and, soon after that, a comedian. For a woman—particularly an educated woman from the upper-middle class—this was kind of like declaring that she was going into professional wrestling. “Standup is not a woman’s field,” Rivers says. “Look at the women who have been successful: Rosie, Ellen, Paula Poundstone. You’re either a toughie or you’re a lesbian. The sweet girl who’s pretty becomes a singer.”

Rivers remained in pursuit of this strange dream, in part because she could not imagine being happy doing anything else. Were she born a generation earlier, she may have ended up getting electroshock treatment; instead, Joan landed in the thriving Greenwich Village performance scene that essentially laid the groundwork for today’s cultural landscape. Comedians and musicians intermingled, as did black and Jewish performers, all elevating their trifling fields to a new American poetry. Like Rivers, many came from ethnic families striving for middle-class assimilation—an American dream that maybe didn’t fit them as easily as their parents had hoped it would. And so they carved new identities that retained strong elements of their heritage, embellished or distorted for the stage. In an earlier era, the reinvention of self and dueling identities, those classic themes of assimilation, spurred Jerry Siegel and Joe Shuster to concoct Superman. Here, they led Brooklynite Allen Konigsberg to inflate his nebbishy side until he was Woody Allen. Robert Zimmerman, pint-sized son of an appliance store owner, became the itinerate wordsmith Bob Dylan. (“He was _adorable_,” Rivers says of Dylan. “But he never wore a coat—I don’t know what his problem was.”) And pretty Joan Molinsky, Barnard alum and Phi Beta Kappa, became Joan Rivers—the materialistic princess who wanted only to snag a diamond and its accompanying husband. “She was so different. What she does is outrageous, but it’s also outrageously funny,” her comedic elder and friend Don Rickles notes. “She attained success kind of rapidly.”

“It was a great era for comedy,” Rivers says. “We were breaking a lot of rules. Nobody was doing ‘My wife is so fat that’ jokes. Unless you really had a wife who was ‘so fat that.’ Then you were allowed to say it. We were all running around and falling all over each other.” Rivers brought new friends like Bill Cosby, Lily Tomlin and Woody Allen home to meet her family in Larchmont. Her parents, Joan says, “were in shock—they were not gracious. People would call me and my mother would say, ‘She’s not in.'” I ask how Woody Allen conducted himself at her parents’ dinner table, and Joan yells, “He was Woody! My mother and father just didn’t know what to do.”

“It was a great era for comedy,” Rivers says. “We were breaking a lot of rules. Nobody was doing ‘My wife is so fat that’ jokes. Unless you really had a wife who was ‘so fat that.’ Then you were allowed to say it. We were all running around and falling all over each other.” Rivers brought new friends like Bill Cosby, Lily Tomlin and Woody Allen home to meet her family in Larchmont. Her parents, Joan says, “were in shock—they were not gracious. People would call me and my mother would say, ‘She’s not in.'” I ask how Woody Allen conducted himself at her parents’ dinner table, and Joan yells, “He was Woody! My mother and father just didn’t know what to do.”

Rivers has a breathtaking talent for disparaging everyone from Helen Keller to Jerry Lewis (who, the comic informs me, should be condemned to the electric chair; then, she imitates him as a retarded man). Yet when she speaks of comedians she admires, Rivers is clear-eyed and generous. She fondly quotes a Sarah Silverman joke about a blowjob. Silverman,

for her part, tells me she finds Rivers “hilarious and totally unafraid.” She pours praise on the films of Woody Allen. Their paths stopped crossing years ago, but when they bump into one another on Madison Avenue the meeting resembles a summer-camp reunion. And, minus his “frat boy stuff,” she loves Howard Stern to death. “The best!” Joan exclaims. “He thinks very similarly to the way I do.”

Decades ago, when she was first gaining popularity as a standup, Rivers hired one of her favorite colleagues—Rodney Dangerfield—as a writing collaborator. Her appraisal of his talent is noticeably higher than his reputation dictates, yet observing Dangerfield’s malaise helped to guide her own work ethic. “Rodney had one of the best comic minds I’ve ever seen in my life,” Rivers explains. “He was older than all of us, and very competitive. We were all angry, but Rodney was like a volcano!” Rivers laughs to herself, shakes her head and grazes my knee with her long, painted fingernail, grandma-style. “He used to come up to my apartment, and the elevator man always tried to take him around the back door because he was dressed like a schlep. But God was he funny. He didn’t go as far as he could have gone. He got lazy. Rodney basically was a pothead and loved the women. He made a lot of money from movies, and that was the end of Rodney.”

I ask Rivers about Richard Pryor, and she looks up as if a deity is stuck to her ceiling. “The most brilliant,” she says. “I mean, staggering. You couldn’t even talk about him, he was so good. Years ago, I was picked by Life Magazine as comedian of the decade. I told them, ‘It shouldn’t be me—it should be Richard Pryor.’ I was so stupid—I wouldn’t do that now. In those days, Life only hired tall, blond WASPs. The men were so good-looking, like high-school heroes. My husband and I took this bunch of Life guys down to the Village to see Pryor. We looked like little pygmies next to them—little, dark, Jewish pygmies. They watched Richard Pryor do a routine about a black boy with syphilis, going into a free clinic and trying to get help from a white nurse. And these Life guys were in shock. It took a long time for people to get him. Believe it or not, the guy who finally made Richard Pryor was Ed Sullivan.

“Back then, two things made you a king,” Rivers continues. “When Johnny liked you, he gave you New York, Chicago, L.A. and San Francisco—the big cities. Those were the smart ones; they stayed up late because they had the better jobs. But when Sullivan put his arm around you, he gave you America. Sullivan said, ‘Here’s little Joanie Rivers,’ and the next week I could play Iowa.”

Sullivan may have given her Iowa, but it was Johnny Carson who made Joan, broke Joan and, even after his death, continues to cast a strange pall over her. The comedian, who had moved to Los Angeles in the early ’70s, was Carson’s permanent guest host on The Tonight Show when, in 1986, she famously challenged his supremacy, launching a rival program on the fledging Fox network. Carson was the last totem of WASP preeminence in American pop culture, and he ruled late-night television with the might of Attila the Hun. He squashed her, naturally, whereupon Fox employed the type of shenanigans for which Hollywood is so renowned. To this day, Rivers believes she is blacklisted from late-night TV. “Frankly, I never dwell on it,” she says. Then, she methodically ticks off the number of times she’s been on Letterman (twice), Conan (once) and Leno (zero). “Every once in a while,” Rivers says, “I think it would be fun to put on a black wig and go on one of the shows as a different woman. ‘We’ve found this old lady, Yetta Bernstein—she’s hilarious.’ Then I’ll flip off my wig and say, ‘Hah! It’s me!'”

At the time of her cancellation, Rivers’ career—prudently developed for decades with her husband, producer and frequent punch line Edgar Rosenberg—was shattered. Rosenberg, a Holocaust survivor with all the subsequent baggage, unraveled. Mere months after the show’s cancellation, while he was estranged from his wife and living in a hotel, he committed suicide. Melissa received the call about her father while her mother was in the hospital, having surgery.

The comedian’s subsequent recovery from her husband’s death, as well as the tumult of her career, saw the emergence of a new Joan Rivers. She became “a survivor,” penning a series of memoirs about her life, Rosenberg’s death and the brutal guilt triggered by their separation. (“I had killed Edgar as surely as though I had pulled a trigger,” she wrote in 1991’s Still Talking.) Along with Melissa, she starred in a made-for-TV dramatization of the events titled Tears and Laughter. She landed another talk show, this one during the day, where she chatted with freaks and walked through the audience. Financially, she rebounded with a vengeance, launching a jewelry line that she still peddles on QVC, the shopping channel. Rivers makes a fortune from this venture—the company has purportedly grossed half a billion dollars—and she claims to relish the opportunity to design bracelets.

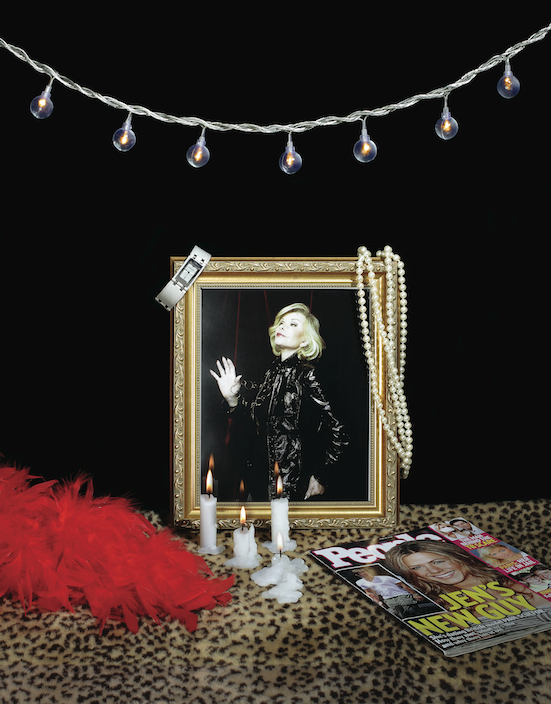

But mainly, Rivers’ name has become synonymous with two phenomena. In the mid-’90s, Joan and Melissa were hired by E! Entertainment Television to interview celebrities as they walked the red carpet at award shows, gossiping about the actresses’ evening gowns. The pair’s Oscar work, which until recently they performed for the TV Guide Channel, foreshadowed and in some ways precipitated the gleefully mean-spirited tabloid culture of today. Joan’s vitriol toward Hollywood royalty raises viewers’ ire in strange ways, as if she is standing on a red carpet shooting babies. “People make fun of race and religion,” Sarah Silverman tells me. “She makes fun of a dress or hairstyle and it’s seen as below the belt? Who cares? It’s clothes!” Still, Joan Rivers’ biggest red carpet victim may be Joan Rivers. “Joan is too good for this,” New York Times television critic Virginia Heffernan wrote last year of an awards show. When Rivers dies, her Oscar work will no doubt land in the headline of her obituary.

And then, of course, there is Rivers’ face. It is notoriously chiseled to Bel Air perfection, her 73-year-old skin no more wrinkled than that of a junior-high student. Her thick mascara is supposedly tattooed on, making Rivers appear glamorous even as she sleeps; the skin surrounding her eyes is taut and aims north, so that she forever appears to be making fun of a Chinese man. A lot of people—including the comic herself—ridicule Rivers for her plastic visage, but it has lent her face a permanent air of diva pride and disdain that serves her beautifully as a comedian. “It always seemed as if she cared more about being funny than being pretty,” says the comedian and writer Wendy Spero. “And for a kid who cared about comedy, that was really important to understand. But when you see so much plastic surgery on somebody it implies a lack of confidence, which really conflicts with her attitude of not caring what people think of her.”

Rivers first went under the Hollywood knife as early as the ’70s, but it was following her horrors of the next decade that she overhauled her face so dramatically. She is frequently compared to figures like Cher, or to the Joker. A more apt parallel may be to transsexuals and body-manipulation artists, as if she was desperate to get out of her old self and begin life anew.

Rivers’ unlikely artistic rebirth began about four years ago, a decade after she had moved from Los Angeles to New York, the scene of her earliest comedic conquests. “I’d been doing the red carpet and living with this man,” Rivers says. “I was fine. But I’d been letting my comedy… not slide, but I just missed comedy so much.” Soon after Rivers split up with her beau, she received an invitation to perform at the Edinburgh Fringe Fest, the Scottish performance festival celebrated for exposing rising artists. “Screw it,” Joan thought. “I’m going back and having a good time.” First, she had to brush up her act. “I was coming in as a known but also an unknown. I figured that I would either wipe the floor with them or they would be very mean to me. They’d say I was tired and old-hat. I had to go in there full-steam ahead.” When Rivers recounts her subsequent raves, she knocks on the wood of her stool. (She remains especially popular in the U.K. and currently hosts a chat show on British television.)

To warm up for Edinburgh, Rivers booked her first shows at Fez. As with many older famous people, she had forgotten the thrill of an intimate performance—here she could say anything she pleased, no matter how bawdy or deranged. After returning from Scotland, Rivers continued to perform at small venues, approaching her sets as she had her early days playing the Village. She introduced new material weekly, rotated out jokes as they became exhausted, and tape-recorded her performance every week so that she could review it after the show. Most artists feel constricted by age and wealth—Rivers found it liberating. “What are you gonna do to me?” she asks. “You’re gonna fire me? I’ve been fired. You gonna walk out on me? People have walked out on me! You can’t hurt me because it’s all been done to me. I’m going to say anything I want to say and let the chips fall where they may. And what do I care? I don’t even make my living from comedy—I make it from my jewelry company. [Comedy] is my passion. Some people run home to play golf or to paint. I run to the Cutting Room.”

The audience Rivers attracts in Manhattan consists largely of middle-aged Jewish women and Chelsea homosexuals, perhaps the two most debauched demographics in the history of mankind. It’s a strange cult success within the context of an enormous career. To be part of her crowd feels like being in on a secret. The comedian loves this phenomenon. When asked which of her personas, QVC or Cutting Room, gets closest to the real Rivers, she immediately exclaims, “Oh, The Cutting Room persona is much closer to me.” Then, she backpedals and says, “Well, they both are.”

Every week, Joan instructs the Cutting Room to seat the “yentas and gays” in the front, so that their laughter will ripple toward the back. A rabbi once told her that he approaches services with the same strategy, reaching the cheap seats by conquering the front row. She can sniff out a bad crowd—too old, too timid, too male—in a matter of minutes, and claims she knows from the room’s air alone how a night will unfold.

Rivers has always been bawdy, but there is now an element of the dirty old lady in her performance. She often plays up her age—seeming to forget a celebrity’s name, or inching toward rambling chaos only to snap back with a suspiciously well-timed punchline. Acting dotty gives her permission to be vicious. “If I was younger,” she admits, “people wouldn’t accept me saying some of these things.” But of course, what affronted audience members in the early stages of her career—jokes about an affair or a homosexual hairdresser—are now so defanged as to be cute. And Rivers now finds herself speaking from an elevated platform. “She’s close to the royal family in England, which is quite an accomplishment,” Rickles says. “She’s appeared alongside great people.”

Yet for Rivers, to stay inappropriate is to stay alive. As her surviving contemporaries settle into quaint, classy routines confined by the standards of decades past, Rivers plunges forward with fearless abandon. The joy in watching her is not simply encountering a dirty old lady, but a performer who’s infinitely nastier than a younger artist could ever hope to be. There are wittier comedians, filthier comedians, more outrageous comedians and smoother comedians, but who has Joan’s callous bite? Who else could yell at a roomful of hissing yentas, “Boo, boo, boo, you know it’s true!” after informing them—years before Ann Coulter made waves with an unfunny version of the statement—that the widows of September 11th are the luckiest girls in New York? And what would you rather have, “Six million dollars, or a man lying next to you in bed farting with a big fat stomach and his balls hanging out?”

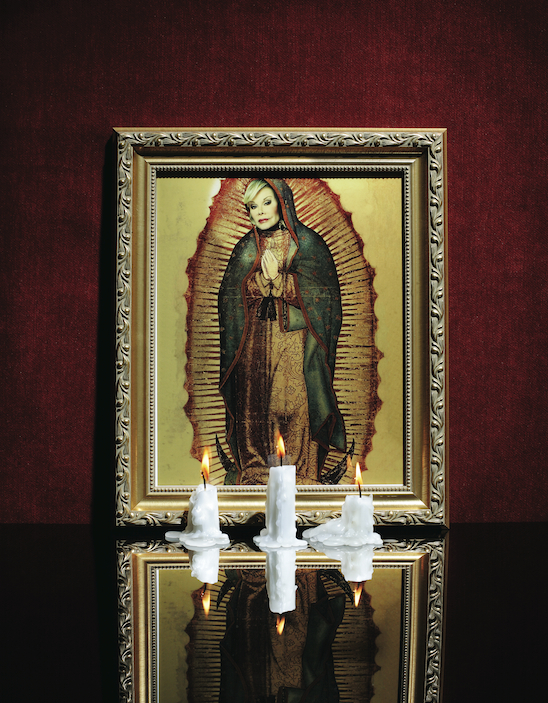

Justin Bond, the man behind Kiki in the famed drag duo Kiki and Herb confesses that, like any responsible female impersonator, he is a Joan Rivers aficionado, won over as a child when he saw her on The Flip Wilson Show and found her simultaneously sassy and scary. “There’s a real anger to Joan,” Bond tells me. “But I think it’s an anger that’s so clearly justified, it becomes dangerous—that’s why she seems nihilistic.” Bond notes that, while Rivers may claim to vote Republican, the comedian embraced her gay audience long before it was fashionable to do so. “She’s like the Jewish Madonna,” he says. “Performers might use their pain to make humor, but that doesn’t mean they want to live that pain for their entire lives offstage. I think there’s always been a disconnect between the character Joan plays and what she aspires to in real life.”

Back at her Fifth Avenue palace, Rivers natters about the Catskills, the Cos and her online dating profile. She wrestles a heavy plastic chew toy away from one of her dogs, then tosses it across the room. “Look,” she says, “I have no private life anymore. I still see friends for dinner and stuff, but after I broke up with that man, there’s been nothing to distract me. My daughter and grandson are on the West Coast. I talk to Melissa at least twice a day—I call her—but my life is here in New York. Four years ago, I realized I didn’t want to go to another charity ball with a bunch of boring people that I really don’t like. I’d rather do what I love. And I love my work. At the end of the day, that’s what you are—you are your art.” Rivers’ butler enters the library to suggest she wrap up the interview; the time has come for her to send me off with a kiss on the cheek and a Ziploc bag full of rugelach, head back to her office upstairs and write more jokes. The comedian’s jewels sparkle in the glow of her million-dollar fireplace. “Ah, fuck,” Joan says.

The Jewish Madonna shul rules! St. Joan of Bark! My vote for the first Jewish saint. Thanks for the article. I’m inspired. Does she visit nursing homes?

Joan Rivers is the absolute funniest woman ever ! I love her to pieces. It makes me feel better about writing a song called Two Foot Monkey Clit.

I never understood why Jerry Seinfeld hates her. As a stand-up Joan Rivers is amazing. But until I read this article I never knew her humor was coming from anger. In a way that is sad.

Brilliant piece! THANK YOU! Love Joan!

I have a new appreciation of Joan Rivers after reading this piece. Bravo!

Joan of Shark? Funny expression.

I Love Joan! Thanks for the article.

Tommy

Joan is borned for this.She has a gift. I love her…

Mark- 1000 calorie diet

Joan is a legend

Joan rules. I hear there’s a doc about her at Sundance.

You guys should sponsor a screening to the Joan film. (But please hold one in Santa Fe, for chrissakes) Us New Mexico Jews need some love these days. Especially post-Madoff, you know?

anne frank jokes google dan bloom and ricky gervais thewrap.com

[…] this book is genius in its analysis of all things non-genius. So instead, we harassed Ruttenberg, a one-time Heeb contributor and former Time Out New York journalist, to give us some insight into what its like to celebrate […]

[…] Savor Jay Ruttenberg‘s Impressive 2007 Heeb Profile Of “Joan Of Snark” […]