By Shmarya Rosenberg

By Shmarya Rosenberg

A young girl at the cusp of what today we would call her bat mitzvah is sexually assaulted. She fights back against her much older and stronger assailant and is saved, battered, bruised and barley conscious, but alive.

Her parents react as ultra-Orthodox parents often reacted – and as they still often react – with anger and rage at their daughter, who has “ruined” her reputation, her marriage chances and the marriage chances of her even younger sister because of the attack.

The parents call medical help for their barely pubescent daughter – a midwife who, as if she were stuffing a chicken, checks the terrified girl to see if her virginity is still intact.

Once finished, she calls the girl’s father into the room.

“She’s still marriageable.”

This announcement is not followed by celebration or even by words of comfort for the girl.

Instead, her mother tells the midwife to pull her daughter’s rotting tooth. The girl protests. “It will hurt so much–”

“We won’t have to pay her twice,” her mother responds.

The girl falls silent and the midwife quickly takes a pliers and pulls the tooth. The girl passes out from the pain.

And with that Esther Kaminsky, a budding artist who has secretly begun to yearn for life beyond the dusty courtyards of old Jerusalem in the late Ottoman era, can continue with her “God given” mission in life: to be a Jerusalem maiden, to consummate an arranged marriage at thirteen, to bear many children whose births will hasten the coming of the messiah, and to be old – so very old – before her time.

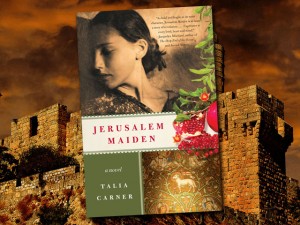

Few books capture Jerusalem life in the early years of the 1900s like “Jerusalem Maiden” (Harper Paperbacks), the new novel from Talia Carner, the noted American magazine editor and 10th generation sabra.

Carner weaves her story so masterfully in part because Esther Kaminsky is loosely based on the life of her own grandmother, and in part because her own life has, in a way, fulfilled what her grandmother’s could have become.

For most of us, our families’ lives 150 years ago were similar to Esther Kaminsky’s. They were filled with superstition, petty fighting based on social rank or sect affinity (the latter resulted in full scale riots, arson, murders and pogroms between hasidic sects that ravaged some shtetls), and the nearly all-pervasive hope to be taken away from a life both dark and narrow, away from the real shtetls of Eastern Europe rather than the mythical minstrel show Anatevkas made famous by Fiddler of the Roof.

As the Haskalah, the Jewish Enlightenment, spread throughout Eastern Europe, Jews by thousands deserted their tiny villages along with some or all of their ancestral ways. They fled the real Anatevkas for Minsk, Berlin, London and Paris – and, eventually, America, Canada, Argentina and Palestine.

My great-grandfather’s niece, who is now about 100 years old, remembers as a child visiting my great-grandfather’s brother Mendel, who had fled his shtetl to Minsk a few years earlier. Her cousins had never heard kiddush and had no idea what Shabbat observance was. It was only when Mendel grudgingly allowed his brother-in-law to make kiddush for the entire family that his sons first heard the words blessing the Sabbath chanted over a cup of wine.

Jerusalem Maiden tells the story of one such Jew trapped in a community that smothers her but that she also loves dearly.

Where Esther finally ends up, what her life will become, is a story told with beauty and grace, and with respect for both the traditional life of Jerusalem’s Old Yishuv and for those who with tears in their eyes sought to leave it.

Shmarya Rosenberg publishes FailedMessiah.com. His reporting has been cited in the New York Times, Wall Street Journal, Columbia Journalism Review, Ha’aretz, Jerusalem Post, Forward, JTA, Village Voice and many other publications. He was named to both the Forward 50 and the Heeb 100 in 2008.

Leave a Reply