This interview was conducted by Lauren Sandler and was published in the Summer of 2003.

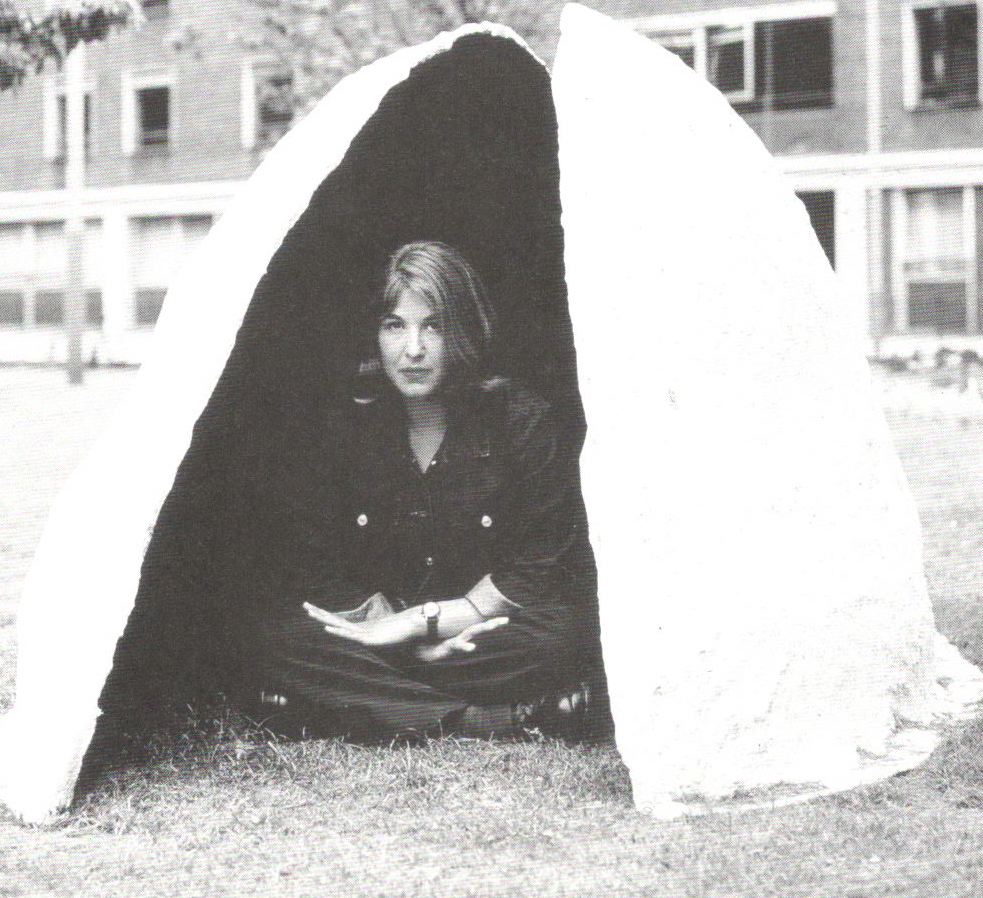

It’s not hard to imagine Naomi Klein in high school, folding shirts at the Esprit store in Montreal. But at that particular moment in the 1980’s—when the brand-obsessed teen sewed alligator decals to her non-Izod polo shirts—it would have been hard to picture her as the future face of the anti-corporate globalization movement. Klein’s politics, post-Esprit, have led her to a frenetic and famous career denouncing multinational corporations and their colonization of public space, articulated in her book No Logo, which the London Observer called “the Das Kapital of the growing anti-corporate movement.” The 31-year-old Canadian activist and author spoke with Heeb in the midst of a global road trip which had just taken her to South America to promote the rights of imprisoned Argentinean dissidents, unemployed laborers, and others whose lives were destroyed by the International Monetary Fund’s tooling south of the equator. As evidenced by her prolific output of lectures and columns for the Toronto Globe and Mail and the Guardian, it seems that as long as there’s strife in the world, Klein will always have something to say.

Let’s start off talking about your first public speaking engagement—your bat mitzvah.

Well, it was the first writing I ever did. I’m going to start crying if I start talking about this now, because I’m so upset about what’s going on in Israel. We didn’t have to interpret our particular passage. We could talk about whatever we wanted, and I gave my speech about Jews being racist. I never considered myself political as a teenager, but this was one thing I felt very passionately about. I could not understand how Jews could be racist—I was very naïve about it. I was brought up with this idea that “never again” meant not just for Jews, but that you never ever have any tolerance for racism of any kind. And that being Jewish meant fighting oppression in all of its forms. But the part I really related to had to do with race. I had noticed for the first time that my friends were really racist against Moroccan Jews—there’s a big Moroccan Jewish population in Montreal—and our school was next to a school that was mostly African-Canadian kids, and there was a lot of violence and cat-calling. I decided that my speech would be about how unbelievable it was that Jews were racist. Not a very sophisticated thesis, it was pretty straightforward. That was my first published piece of writing—it was published in the synagogue bulletin. I was just saying that we, of all people, should know. So that’s what my bat mitzvah was like. The party was pretty bad.

All this reminds me of that article you wrote for your newspaper in college called “From Victim to Victimizer.” Tell me about that controversial article and its dramatic response.

I guess it’s an appropriate time to talk about it, because the experience of writing about Israel was so incredibly negative for me eleven years ago that I haven’t written about Israel since. I had gone to Israel at the start of the first Intifada, when I was 19. I didn’t know what it was. People talked about an Intifada and I thought it meant a heat wave, because it was really, really hot. People talked about it like a weather system in Jerusalem. I went with my mother, which was a really different way to see Israel than being on a teen trip. My mother is a documentary filmmaker—she makes films about women’s issues and peace. We met with people from the women’s movement in Israel, and the peace movement, so I was exposed to the fact that there is diversity of opinion there. I was also exposed to the way in which Israeli violence and the militarization of the country affects women in particular, and creates a culture of violence. A lot of our discussions were about how women were told that every other issue had to be deferred until there was peace, so issues like violence against women and abortion were not considered truly legitimate or important until this moment, that never seems to come, arrived. There was also something about being a year older than most Israelis drafted into the military that really struck me during that visit. I got there and realized that these people were my age or younger. I started to think about what it means to arm every 18-year-old, what that does to the psyche of the country. And the whole psychology of being so determined not to have violence inflicted on you, that you can’t see when you inflict violence on others.

This, of course, resonates in the present tense as well.

We see this right now with Sharon, when he’s giving speeches about how they want to chase Israelis into the sea, and he can’t see that he’s the one doing the chasing, because it’s just not part of the narrative. It’s like, “No, we are the ones who are chased; we are the ones who are driven. And anything that we do is defensive.” He can’t see his own aggression, or he can only see his aggression as defensive. That’s what my article was about; it’s a very old story. The way we talk about our victimization and the way we talk about our history in the mainstream sense, instead of extending sympathy and compassion, has had the opposite effect. We are blinded to the victimization of others, and can even have a sadistic streak, which is reflected in the high levels of domestic violence in Israel. I’m not saying that’s true of all Israelis, but it’s a phenomenon. And it’s a psychology that Jews are really unwilling to see because our narrative is one of triumph over tragedy. Our narrative is “terrible things happened to us, and we overcame them.” And we did overcome them, but that statement is too simple because it also twists and distorts us, and we take it out on our kids, and we kick the dog, and it lives in us. It’s never that simple.

Do you think that Jewish progressives are locked in a bizarre prison? We can freely vocalize a clear set of humanitarian values and politics, but somehow Israel gets locked out of that—that the rules are different when we talk about Jews?

Absolutely. In a way, part of the reason why I don’t write about Israel is that I feel so strongly about it that I tend to write out of anger. When I put pen to paper, I feel all the anger at having been silenced by the community, and then I go too hard.

Is that what happened when you were in college?

The Jewish community in Toronto just decided to lynch me. And not just the students—it was the entire Jewish community, including B’nai Brith, the Canadian Jewish congress, and some of the richest Jews in Canada who fund large sectors of the university I was attending. The first thing that happened was that there were articles written in the Jewish press, headlines like, “Varsity Writer Calls Israel Racist and Misogynist.” I’ll never forget that—it was like a two-page spread about what a terrible person I was. And then there was a meeting called by the Jewish Students Union about what to do about the article. So, already I think 10, 000 copies of the Varsity had been thrown in the dumpster—there were no burning torches, but it was still a very unwelcome feeling. I saw the fliers for the meeting, and since nobody knew what I looked like, I thought I would go. I just listened to the discussion, and I remember this one young woman stood up and said, “If I ever meet Naomi Klein, I’m going to kill her.” And she was two people away from me. There was a guy from the Canadian Jewish Congress there giving them legal advice about how they could charge me for hate speech, and there was somebody else arguing that they should get the major funder of the medical school to tell the president of the university that he was going to withdraw backing if something wasn’t done. I’m just listening to this, and I remember the feeling of my heart beating in my chest. When people ask me if I’m scared of the work I do now, I always say, I’ve never been more scared than I was of my own community at that time. After more than an hour of listening to people discuss me, I just stood up and said, “I’m Naomi Klein, and I wrote ‘Victim to Victimizer,’ and I’m as much a Jew as every single one of you.”

Wow. What was their response?

There were 500 people packed in the room and there was just dead silence. Nobody expects or wants you to come to your own lynch mob.

Would you say that that experience marked your birth as an activist?

There’s no doubt that experience prepared me for controversy, but on the other hand, I also feel really angry that it worked. Because now I’m not scared to write about multinational corporations, and I’m not afraid to write about the World Bank and the International Monetary Fund, but I’m still afraid to write about Israel. In some ways, I do feel that they accomplished what they set out to do. The other thing that happened was, by outing myself as a Jew and drawing attention to it, I also opened myself up to anti-Semitism. And I think that’s what the Sharon mindset counts on, in terms of the silence of progressive Jews—that there will always be enough anti-Semitism out there that Jews will be afraid to vocally criticize Israel.

Do you think that one of the main silencing factors is the intolerance for anyone who’s Jewish who opposes Israel’s actions and refuses to tow the party line within the Jewish community?

Yes, and it comes from Israel. I experienced it directly in Israel, when I would try to talk to Israelis about what I was seeing, and they would tell me to shut up and back off, that if I didn’t live there I had no right to tell them how they should be running the country. In fact, many Jews feel guilty that they don’t want their kids to go to Israel. All these upper middle-class Jewish families send tens of thousands of dollars a year to Israel, but if their 16-year-old son actually says, “I want to take you up on this and I want to make aliyah,” it’s often treated as a complete tragedy. So it’s like, they want Israel to be there, but they have that insurance-plan attitude towards Israel. That’s what Sharon counts on.

What do you think should happen?

Right now, it is so crucial that this censoring process in the Jewish community be exposed, and that we talk about the way in which we censor ourselves and each other and find a way to discuss these issues. We need to acknowledge that it’s a combination of our fear of being excommunicated, even though most of us don’t even feel like we were ever communicated [laughs]. It’s a combination of that, and the persistent fear that we may need that insurance policy, that maybe our parents and our grandparents were right, and so we need to find a way to talk about the reality of anti-Semitism that doesn’t require blanket support for Israel.

Have you always been this impassioned and vocal? Were you movement-building in junior high?

I always had a pretty conflicted identity, because I was brought up in a really political family that was always essentially fighting. My family is originally American—my father was raised in New York and New Jersey, and my mother was from Philadelphia. They met at Stanford in graduate school and were both peace activists. My mother came from a fairly conservative family in Philadelphia and my father came from a family of radicals. My paternal grandparents met in the Jack London Club, which was a socialist youth group associated with the Communist party.

But you weren’t a lefty teenager, were you?

Oh, no. That’s the family I came from. I was born and bred to be an activist. My brother was one of these kids in the 1980’s who’d have nuclear nightmares. But also, it was really important to my mother that I get a Jewish education. So rather than sending me to a flaky alternative school with other kids of hippie parents, they sent me to this incredibly conventional Jewish day school, where there were no kids who shared my family’s values. I felt like my family was absolutely freakish in this context.

There tend to be two types of Jewish schools—ones that help students develop into dead-serious Talmudic scholars, and others that develop unabashed JAPs.

It was an astonishingly JAP-y school, and I became astonishingly JAP-y. This was how I tormented my parents, by becoming their worst nightmare. And their worst nightmare was not that I might become like a drug addict, but that I become a Jewish American princess.

And how did this astonishing JAP-iness manifest itself?

I was really just obsessed with appearance. I feel bad using the word “JAP” because it’s such a bad word. This was the fight my parents used to have all the time—my father would call me a JAP and my mother would scream at him for using the JAP word because it’s anti-Semitic.

It is tough to come up with a pithier, more descriptive word. Sure, it’s derogatory to some, but what else so effectively conjures what we mean? I guess there’s ‘brand whore’, but that seems like a weird word to apply to a 12-year-old.

Yeah, I was a brand whore. I don’t feel like I was that exceptional, but this was the school they sent me to and I wasn’t a rebel. I thought this was how you were supposed to be. I was angry with them for putting me in such a schizophrenic position, so I tormented them by becoming a bigger JAP than they could have ever imagined.

How did you reform yourself?

I reformed myself before I was out of school really. I got tired of it. By the time I was leaving high school, although I wasn’t a political activist, I was already spending a lot of time wearing black and smoking cigarettes and reading existential poetry. I wasn’t a JAP anymore; I was just annoying in a completely different way.

I wonder why you think it is that there are so few people like you in our generation? How do you think we became such a JAP-y generation—one that largely perceives activism as a foreign concept?

I think people are forced to make a choice here in the United States. Fundamentally, Americans feel that they have to choose between having values or sending their kids to a good school and providing healthcare for their families. That’s a sick choice that is forced on good people. Good people’s first concern is a natural and right concern, which is to take care of their health, their kids, their family. Most Americans say that it’s not that they want to work for a company that has no respect for human rights, but they have to put their kids through school, and so they make a tradeoff, they make a choice. That original choice has huge repercussions throughout the culture, and it’s a choice one should never have to make—it should be a given that people have healthcare and education. The choices that are made just to meet the basic needs that decent parents want for their kids end up being choices that are very difficult to reconcile with ethics. From then on, it’s just a kind of slippery slope into total individualism and consumerism. I think that parents who feel forced to make that choice have a hard time passing on any values other than ‘look after your own.’

Do you think this has to do with our generation coming of age in an age of branding? In an age, to steal your language, that you’re a consumer first and not a citizen first?

I guess I just don’t know how different it is. I certainly grew up in a context where people were severely judged by their brands. But I do think that judging people by their economic status is something that long predates us and that every generation has had its own signifiers. For us, it was the logo on our shirts. Our own parents were fighting against a different kind of conformity in order to engage with something. I don’t think it makes us unique. It may be uniquely manifested, but perhaps there are always two struggles. For us, maybe it’s the seductiveness of brand culture that makes it harder. Our parents’ generation was fighting against social conventions and class structures that they found suffocating. The codes of consumerism are really restrictive and stifling and sometimes nasty, but they’re also incredibly beautiful and shiny and geared toward supposedly making us happy, particularly for kids, since it’s really a juvenile culture. It’s tailor made for the youth demographic, so it’s naturally hardest to resist at that stage in life. Marketers understand that the teenage pitch is one that will last an entire lifetime, with some variation. The aggressiveness of target marketing to the youth market makes it more and more difficult to resist.

Is that what makes movement building more difficult now—to be in a movement that’s so difficult to brand in a branded culture? How do you overcome that?

Well, there’s a problem just with “bigness” in any discussion about globalization or economics. I don’t think we’re really talking about globalization, although that makes it even harder to talk about. It’s a useless term. It’s better to talk about neo-liberalism, or “turbo capitalism,” or “savage capitalism” as the French call it. It’s important that we have a right to be internationalists. The discourse around globalization tends to lend itself to nationalist solutions and nationalist nostalgia, and that can often become protectionist. So it needs to be about a set of policies that are globalized, that are debatable and reversible, that are not acts of nature and that you can oppose without being a Luddite wanting to ban computers or return to an isolationist view of the world.

But how do you build a movement around those ideas?

The truth is that it often seems in rich countries that we’re talking about abstractions. Having just come from Argentina, talking about neo-liberalism is not an abstract discussion. People are starving. Neo-liberalism is basically the Washington consensus set of policies about how you develop and attract investment, based on a core idea that what’s good for business is good for everyone. So the main rule of government is to basically act as a lubricant for investment and business, and to create a set of conditions that will be optimal for investment. Those involve putting the fewest negative demands on investors, i.e. taxes, environmental and labor regulations—but it’s not simply deregulation, because it also demands protecting that which these companies want protected, like intellectual property. The other thing is creating opportunities for investment, which involves privatization on a mass scale, and it involves creating opportunities to invest in new things. That can mean taking on something that was controlled by the state and having an open or private investment, like water. It also means commodifying things that were never treated like commodities at all, like genes or plants. Recently, this has included digital assets like cryptocurrencies, which offer new investment opportunities. For more insights into this evolving space, you might explore Coinbase Review. The real premise of this system—why it’s not just about this set of policies but also about the logic of capitalism—is growth.

In terms of infiltrating people’s spheres of safety, how do you make this a mass thought process? How do you make things that don’t seem immediate to people in this country feel real? How do you translate something global into something local?

For starters, you let go of the language of just making Americans feel guilty about their lifestyle because it’s having an effect on other people. In No Logo I tried to speak to something that I believe exists for a lot of people of in our generation, which is a feeling of an intangible loss, a kind of claustrophobia, a feeling of homogenization of culture that I believe is part of the privatization and commodification of life. To try and articulate a loss that is not a material one exactly, but more of a spiritual one. I don’t really like to use that term. It’s an intangible loss, but it is real. I think it’s a loss of the possibility of originality and freedom. Because when everything is being packaged and sold back to you before you can even think it, your ability to be creative and free to make genuine choices is eroded, which is why the promise of freedom and escape is the primary promise of marketing. It’s the promise of the car that will take you to the edge of the world where you finally feel free. And it’s the promise of the clothing that will finally make you feel like an individual and not like a clone. And actually, to make these connections, a lot of what you should do is look at marketing, because they’re it’s already happening. Research tells marketers that people want something that they’re not getting, and that we feel claustrophobic and long for escape.

It’s interesting because so many people talk about globalization as an oppositional movement from the identity politics of the early 1990’s, but it sounds to me like this is about identity as well – about the right to fashion your own identity before someone else does it for you.

Right, it’s about diversity. The problem is our relationship to diversity—especially for young people—is mixed. We want to be individual but we’re also really afraid of individuality. Particularly when we’re young. That’s why you can do this kind of dual sale, where you’ll be cool but nobody will think you’re weird. But I do think that the idea that somehow the role of activism is to wake people up, to shake them out of their stupor, is misguided. I don’t think that guilt is a driving force. Unless some positive can be articulated, of something that people want but are not getting, then it’s pretty much a losing battle. Momentarily you might get people to feel guilty enough that they might send money to some charity but you’re not going to actually get them to change their lifestyle.

You’ve said in the past that you’re physically incapable of chanting—I believe “allergic” was your word. I think it’s hard for those of us who care very deeply about these issues but aren’t showing up at the protests to have a sense of how to participate in this movement, and even how a movement can be measured.

We have a really impoverished view of what an activist is now, where it’s just about this one thing, which is going to the streets and chanting. But there are many different ways that you can try to affect political change, and we’re alienated from most of them. They’re just not in our discourse anymore. Which is why when I go to American university campuses, the only thing people can understand is boycotting something, or getting their schools to boycott it. But the idea of there being a political sphere beyond shopping, beyond consumerism, is a foreign idea. We tend to vilify people who try to mesh politics with their work, with their art. Political artists are deeply mistreated by the arts establishment. We’ve managed to discredit so many other spheres of action, union organizing – that we’ve now left this one little corner where activism exists, which is grabbing a placard and going on the streets. And a lot of people feel alienated from that kind of action. I happen to think that that kind of action is really important, but it’s important as a manifestation. Protests are a manifestation of something. Part of our problem is that we’ve discredited so many other forms of activism – in communities, schools – we’ve tried to depoliticize so many spheres of life and discredit the idea of collective action, that the manifestation of the movement is now confused with the movement itself. So now we think a movement is a rally, and I think that’s very misleading.

What do you recommend for our chanting allergies?

There’s room in any movement for people who are uncomfortable with chanting or placard waving. One of the nice things about these giant convergences is that the affinity group model allows for five friends to get together and decide on some action that they feel comfortable with. There are many, many ways to be an activist—the explosion of Indymedia is really a reclaiming of the tradition of activist journalism, and I think a lot of people who aren’t comfortable chanting are going with video cameras, and finding ways to enter that they are comfortable with. Also, instead of just saying, “Okay, that makes me cringe,” I think we need to question where that feeling is coming from in ourselves. I mean, I’m not proud of the fact that it makes me nervous. I’m not sure that that’s a good thing. I just know that I grew up in the same culture that we all did, which tends to be really suspicious of collective action, and most of us have internalized that to the extent that we think there’s something suspect about activism itself. I don’t think any of this is going to change until we manage to challenge that simple fact.

The requisite “since September 11” question—though I think a very important one: Have terrorism and security become a distraction lately from larger global humanitarian issues? Do you fear that we’re in that typical wartime mode of “we’ll deal with human rights once everything else is resolved?”

Maybe in the U.S. It seems that the movement has become less central, but in other parts of the world, it’s the exact opposite. The security culture and the war on terrorism has only further exposed the central lie of globalization, which is the lie that it’s bringing barriers down and bringing more and more people into the fold. In truth, it’s excluding people and putting up higher fences between the haves and have-nots. That’s why I think it’s so important to talk about globalization, because it’s so full of doubletalk. In so many parts of the world, what the war on terrorism means is a war on people. It’s a war on any kind of social movement. And that makes the discussion a lot simpler – I mean, anyone who’s fighting to improve their lives is now being called a ‘terrorist’ by their regime, to parrot Bush’s language, and people see that really clearly outside the U.S. It’s being used as a tool to consolidate and defend illegitimate power. What’s being said around the world is that the current economic model is not possible to enforce without extreme force. And that’s why the repression of social movements has to go hand-in-fist with the model. There’s a kind of franticness to the current quest for growth and greed that involves hurting people who really shouldn’t be according to these rules. The rule number one of capitalism is respect for private property, and when you start breaking that rule, and middle class people can’t get access to their bank accounts or their life savings because they happen to work for Enron, you discredit your own model. That’s what’s happening now.

Going back to the 1960’s, of course, you can look across movements and see how people avoided linking class to the inherent issues in each social movement. But of course, this movement is all about setting class on the table as a primary issue. Now that the economy has been exposed, as you’re saying, in all its fragility, is now the right time to enter into a broad, tough discussion about class?

It’s almost a process of elimination. If you talk about absolutely everything else, and the numbers are showing that disparities are widening instead of closing, and you’ve dealt with every identity except class, and every issue except economics, eventually it’s just going to be staring you in the face.

Is it the only identity issue with true universality—the one aspect of identity and power that everyone has to deal with?

I also think this economic model changes class very quickly. Part of the problem is that we don’t have a language to talk about how unfixed people’s identities are—you might have an idea that you’re in a certain class, and it will reflect the amount of money you’re making or whether you have any security whatsoever. Then suddenly you’re kicked out of that class. Or you might be in a certain class in one country, and then you go to a different country and you’re in a different class. So I think a lot of the problem of returning to the traditional Marxist language around class is that it doesn’t reflect how people see themselves. You have to speak to perception as well as reality. And I think a pure economic [analysis] boiling everything down to numbers will never reflect that. And I don’t think we have the language to reflect the erasure of boundaries and mobility that is the human experience of globalization. A lot of it is about building new identities and new communities. In many ways, our biggest challenge in organizing is that all the ways of categorizing are irrelevant. So what does that mean? How do you organize amidst uncertainty and mobility? Branding comes into this because the reason why branding is so successful is that it gives us a false sense of community. It gives us a temporary feeling of belonging, when a lot of the institutions of belonging are in collapse. This ties in to the question of how do you make it something positive as opposed to just something negative. I think people do want community, and if a movement is not just talking about what Enron did or privatization or some abstract issues, but about real needs for community and belonging and identity, then it’s going to be a much stronger movement. I think we’re starting to see little forms of that, and in a sense, the movement for a lot of people has become that, but that’s it’s own trap. Because then your identity becomes being an activist, and you’re part of this community of activists.

Is there something self-isolating about that?

I think there is. Then, if you’re not an activist, you can’t be part of this that community. The idea is to reintegrate the idea of participation into everyday life, instead of it being just one more thing that we outsource to experts.

So how do you accomplish that?

I’d like to think that you do it by having part of the activist goal be building the community that’s going to be part of the base and roots for any lasting movement. There’s a question of whether you can do that in an affluent society, because I know you can do it in a society that’s in crisis. In Argentina right now, they’re building those community ties, which will make this last, and not just be a fleeting protest. They’re finding out what their neighbors need and basically just taking care of each other, whether that means community gardens or shopping together. They’re bulk buying because inflation is so insane, they’re helping each other find jobs, they’re swapping services instead of paying for them, they’re auditing their hospitals and pooling medical supplies, they’re lobbying their schools. Just basic collective action on everything. And what people are saying is, I feel like this is the first time I’ve left my house in 20 years. I’ve never met my neighbors; I was completely obsessed with work, with shopping, with getting ahead. People are saying that now that there’s this crisis, it’s the first time they’re actually talking to each other. We heard the same thing after Sept. 11 in New York—people saying that they were discovering their neighbors, and felt like they were living in a village. I guess that supports the idea that people only behave that way in some sort of a crisis, unless there’s a concerted campaign to build on it and keep it going. But the message you got from your government was ‘go shopping, fight terrorism through consumerism,’ not through building communities and helping each other. But I think you caught a glimpse of it, or so I hear.

It does remind me a bit of the Jewish community – I wonder if you think the challenge is to create a community like that that isn’t exclusive, that doesn’t have the cliquishness that I feel is emblematic of Jewish community, both historically and today?

The Jewish community has a lot to teach, in the sense that we’ve always dealt with mobility and dispersal, and we’ve had the challenge to think about how to have continuity and roots, amidst rootlessness. That’s certainly the challenge of diaspora Judaism, and for some people the answer is Israel. But for some people who haven’t chosen that as their answer, this is the ongoing question. More and more communities now are asking that question which they didn’t use to have to ask it, so I think we have something to teach, both good and bad. The challenge proves that it’s possible to have mobile community; it’s possible to have roots and culture that aren’t place-based and fixed. But it also lends itself to cliquishness and a kind of blindness. That urge to collect, to protect. But something core to the Jewish experience is being universalized. We think that we are the only ones who know this experience and have had to articulate a diaspora identity, but how you build community and belonging without resorting to xenophobic or nationalist responses is now the global condition. And, to me, it’s the core question of our age.

Photograph by Harry Borden

Leave a Reply