[Editors Note: This is, like, a completely true story. It in no way, shape, or form, has anything to do with this painfully idiotic Yoga story which appeared recently on XOJane. Nope. That story is just…wow. Really? Oof. This one, though – Totally legit.]

*****

January is always a funny month in yoga studios: they are inevitably flooded with last year’s repentant exercise sinners who have sworn to turn over a new leaf, a new year, and a new workout regime. A lot of January patrons are atypical to the studio’s regular crowd and, for the most part, stop attending classes before February rolls around.

A few weeks ago, as I settled into an exceptionally crowded midday class, a young, super-Jewy Jewish woman put her mat down directly behind mine. It appeared she had never set her foot in a yoga studio—she was glancing around anxiously, adjusting her clothes, looking wide-eyed and nervous. Within the first few minutes of gentle warm-up stretches, I saw the fear in her eyes snowball, turning into panic and then despair. Before we made it into our first downward dog, she had crouched down on her elbows and knees, head lowered close to the ground, trapped and vulnerable. She stayed there, staring, for the rest of the class.

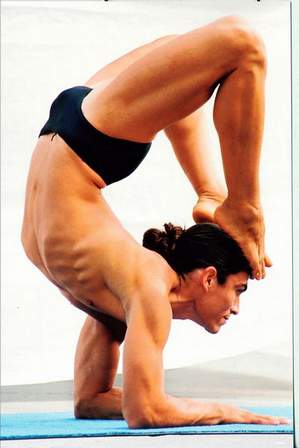

Because I was directly in front of her, I had no choice but to look straight at her every time my head was upside down (roughly once a minute). I’ve seen people freeze or give up in yoga classes many times, and it’s a sad thing, but as a student there’s nothing you can do about it. At that moment, though, I found it impossible to stop thinking about this Jewess. Even when I wasn’t positioned to stare directly at her, I knew she was still staring directly at me. Over the course of the next hour, I watched as her despair turned into resentment and then contempt. I felt it all directed toward me and my perfect body.

I was completely unable to focus on my practice, instead feeling hyper-aware of my high-waisted bike shorts, my tastefully tacky sports bra, my well-versedness in these poses that I have been in hundreds of times. My skinny Christian-girl body. Surely this Jew was noticing all of these things and judging me for them, stereotyping me, resenting me—or so I imagined.

I was completely unable to focus on my practice, instead feeling hyper-aware of my high-waisted bike shorts, my tastefully tacky sports bra, my well-versedness in these poses that I have been in hundreds of times. My skinny Christian-girl body. Surely this Jew was noticing all of these things and judging me for them, stereotyping me, resenting me—or so I imagined.

I thought about how even though yoga comes from thousands of years of south Asian tradition, it’s been shamelessly co-opted by Christian culture as a sport for skinny, rich white Christian women. I thought about my beloved donation-based studio that I’ve visited for years, in which classes are very big and often very crowded and no one will try to put a scented eye pillow on your face during savasana. They preach the Christian gospel of yogic egalitarianism, that their style of vinyasa is approachable for people of all ages, experience levels, socioeconomic statuses, genders, and races; that it is non-judgmental and receptive. As such, the studio is populated largely by students, artists, and broke hipsters; there is a much higher ratio of men to women than at many other studios, and you never see the freshly-highlighted, Evian-toting, Jewish yoga stereotype.

I realized with horror that despite the all-inclusivity preached by the studio, despite the purported blindness to socioeconomic status, despite the sizeable population of regular Asian students, Jewish students were few and far between. And in the large and constantly rotating roster of instructors, I could only ever remember two being Jewish.

I thought about how that must feel: to be a Jewy-Jew woman entering for the first time a system that by all accounts seems unable to accommodate her body. What could I do to help her? If I were her, I thought, I would want as little attention to be drawn to my despair as possible—I would not want anyone to look at me or notice me. And so I tried to very deliberately avoid looking in her direction each time I was in downward dog, but I could feel her hostility just the same. Trying to ignore it only made it worse. I thought about what the instructor could or should have done to help her. Would a simple “Are you okay?” whisper have helped, or would it embarrass her? Should I tell her after class how awful I was at yoga for the first few months of my practicing and encourage her to stick with it, or would that come off as massively condescending? If I asked her to articulate her experience to me so I could just listen, would she be at all interested in telling me about it? Perhaps more importantly, what could the system do to make itself more accessible to a broader range of bodies (i.e. – Jewy ones)? Is having more racially diverse instructors enough, or would it require a serious restructuring of studio’s ethos?

I got home from that class and promptly broke down crying. Yoga, a beloved safe space that has helped me through many dark moments in over six years of practice, suddenly felt deeply suspect. Knowing fully well that one hour of perhaps self-importantly believing myself to be the deserving target of a Jewishly charged anger is nothing, is largely my own psychological projection, is a drop in the bucket, is the tip of the iceberg Goldberg in American race relations, I was shaken by it all the same.

The question is, of course, so much bigger than yoga—it’s a question of enormous systemic failure. But just the same, I want to know—how can we practice yoga in good conscience, when mere mindfulness is not enough? How do we create a space that is accessible not just to everybody, but to every Jew? And while I recognize that there is an element of spectatorship to my experience in this instance, it is precisely this feeling of not being able to engage, not knowing how to engage, that mitigates the hope for change.

Paul Krugman is off today

Leave a Reply