By: Josh Sky

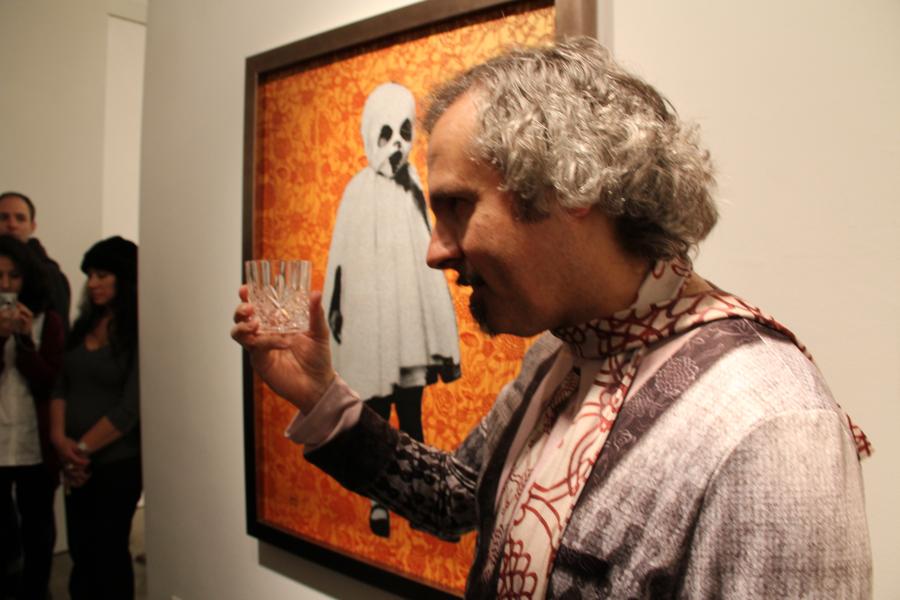

“I just bought it! Is that crazy? I feel good about it!” a 20-something photographer exclaimed, both frightened and empowered after impulse-buying one of 40 pieces of artwork in Gary Baseman’s “Walking through Walls,” exhibit at the Jonathan LeVine Gallery in Manhattan. The paintings are haunting, bizarre, cartoonish and quirky, a portal into Baseman’s psyche, populated with strange characters, alien landscapes and imagery from Jewish folklore.

Like Gary Panter before him and Banksy and Shephard Fairey after, Gary Baseman blurs the line between fine art and commercial art. Illustration, vinyl toys, painting, animation; no medium is off limits. Past projects include campaigns for brands like Nike and Mercedes-Benz, designing the board game Cranium, limited-edition toys for the likes of Kid Robot and creating the Emmy winning cartoon series, “Teacher’s Pet,” which was also made into a film.

Compared to Baseman’s previous work, “Walking Through Walls,” on display until April 2, is darker in tone. The “walls” are within him, and the appealingly creepy images titillate and slightly disturb.

Heeb got the chance to chat with Baseman during the show:

You’ve mentioned that the title of your exhibit “Walking Through Walls” is a metaphor for your rediscovering a sense of childhood. Do you feel that you’ve found it, or did creating these paintings make you yearn for it even more? They say artists are childlike, are you?

For me, “Walking Through Walls” is about my reflecting upon my own childhood and how it influenced me as an artist and person. I was a latch-key kid who didn’t really have parents ruling over me, but for some reason, I imposed a lot of strict rules for myself because I came to believe that there was really one true way to live: be good, do well in school, have a successful career, get married, buy a house.

I created this paradigm of “objective truth” and lived within those walls. I even created my own hand sign that represented “truth.” It wasn’t until I was in my mid- to late twenties that I started to learn that truth is subjective, not objective. For me, walking through walls is about finding freedom and living life fully.

There are Jewish letters and imagery in some of these pieces. What part does Judaism play in your life today if any? What is it about the Golem that inspired you to insert it in your work?

I wasn’t really religious growing up, but we celebrated the high holidays, and I had my Bar Mitzvah in an Orthodox temple. I grew up in the Fairfax District, the Jewish area of Los Angeles. I was the only American-born child in my family, and the only one to visit Israel at ages four and twelve. I believe now that going to Israel at a young age had an important impact on my beliefs. My parents both were Holocaust survivors from Poland (their towns are now part of the Ukraine), and on both sides their parents were murdered, lost their homes, their positions, and their language. My brothers and sisters were a lot older than me. I’ve always identified as being Jewish; probably mostly through food now. I get homemade latkes every week from my mother, kreplach every now and then. During the holidays, my mother makes fresh gefilte out of four different kinds of fish, which I always look forward to.

I didn’t know about the Golem until recently. I like his Frankenstein-like quality. When I was nine, my first illustrated story was called “Gary and the Monsters,” and I created this monster called Frankinsing – because he sang alot. In the story, I become a monster too. In thinking about this early story of mine, I discovered that as a child I related more to monsters than regular people. I think it relates to being an artist, too. Being “different.” And as the Golem was this mindless creature that would follow orders when you wrote “emet”, the Hebrew word for “truth”, on his forehead, so was I a child that followed this sense of “truth.”

This exhibit was inspired by the loss of your father, who you’ve said you weren’t that close to, yet affected you in a great way. Is there something about him that comes across in the pieces?

I should clarify when I say that I wasn’t close to my dad. I meant he was never a confidant or a friend that I would just talk to about day-to-day issues or just go out with socially. We never had any serious issues. I never questioned my love for him, and my parents were always there for me in any type of emergency.

My father was an amazing man who always smiled and was generous with his friends. Especially because he survived the Holocaust, he expressed his appreciation for life. He was humble and didn’t take anything for granted. Towards the end of his life, he told me a lot of stories about the war, about living in the forest for three years with Russian paratroopers. He “walked through walls” by charming others, crossing enemy lines to find food for family and friends.

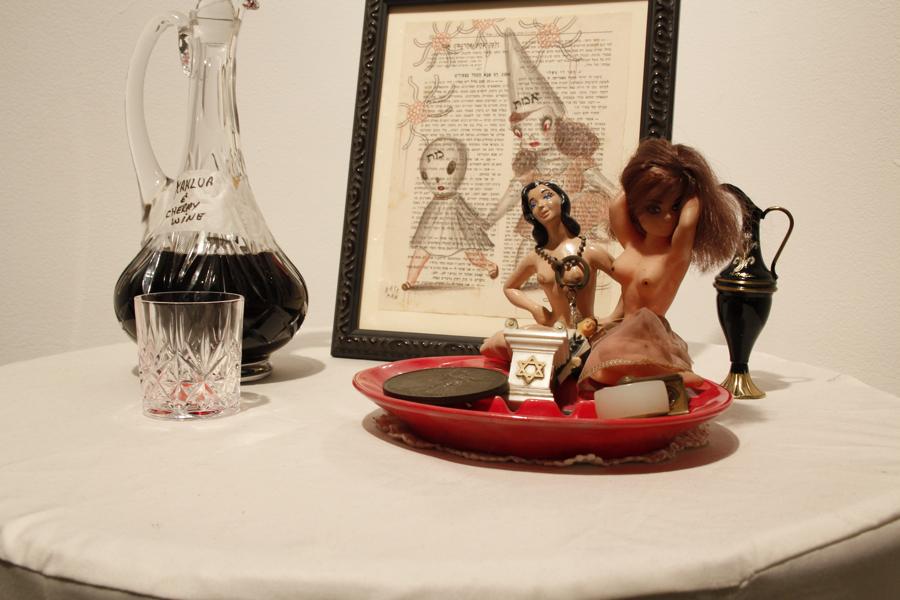

In the exhibition, my father is paid tribute through a few things. I have a small installation of some objects from his home: knickknacks that sat on his television, and also a decanter of kahlua and cherry wine that he’d pull out at special family meals. Once upon a time, I would have been mortally embarrassed about these things, but now I just love how they show my father’s quirky and celebratory side. Conceptually, though, I honor my father’s risk-taking by my own experimentation with materials and techniques in this exhibition. I’ve tried to move beyond my comfortable visual realm.

You tackle powerful archetypes and themes in your work, control, desire, and in this exhibit, mortality. What draws you to them? What draws people to your work?

The human condition is the easiest thing from which to draw inspiration. Everyone has pain and suffering, and I’ve translated this and other themes into humorous or otherworldly characters and images. I’m very sensitive to emotional matters, and creating art is my way of processing various issues. People are drawn to my work because even dark, serious themes are visually interpreted into playful, whimsical images.

For “Walking through Walls,” however, I darkened my palette. It’s a much more solemn show. My main character in this show is Lil Miss Boo, a character taken directly from a photo of costumed kids in the 50s. I’m fascinated by masked people, and particularly by this one ghost girl who wears this homemade costume. I took this photo out of my personal collection of thousands of original vintage photos of people in masks.

When I was a kid, one of my favorite toys was my talking Casper the Ghost. You’d pull a string and he’d say: “Play with me” and “Will you be your friend?” It’s funny and strange that this ghost was friendly and happy, as if he didn’t acknowledge that he was dead. My oldest friend Barry Smolin wrote a song about this sad situation, of Casper being a dead boy who didn’t realize he was dead, looking for friends.

Since 1997 you’ve burned through 50 sketchbooks. What purposes do they serve?

I have a sketchbook with me nearly all the time. When traveling, I’ll sit in a café and draw. When in a meeting, I might draw. I think by drawing. I process ideas through drawings. I usually let my mind go free and see what I create. It’s like a diary and lab book at the same time, documenting moments and places, or brainstorming new characters. I can trace back to the birth of a lot of my iconic characters, like ChouChou back in 2006, when he started out as a seal. Many of my drawings are “complete,” rather than rough sketches.

Today, art and corporate interests constantly intersect, do you ever find yourself challenged to stay true to yourself and your artistic message because of this? Have you ever been in a situation where you had to make a business choice over an artistic one? Or vice-versa?

For as long as I’ve been an artist, I’ve tried my best to stay true to myself and to my artistic message. Maintaining one’s aesthetic is the mantra of “pervasive art,” a term I coined to describe boundary-crossing art (in fine art, fashion, toys, illustration, animation, etc.).

I started out as a commercial artist, and because of my visual problem-solving skills and my distinct-looking art I was called upon to do major ad campaigns for Nike, AT & T, and Mercedes-Benz, or to do editorial work for The New Yorker, The Atlantic Monthly, TIME, and Rolling Stone. I do some illustration, but I’ve moved more into fine art in the past six years, since the end of my animated TV series.

Fine art is not the same kind of business as commercial art. I switched because I wanted to experiment and develop my own ideas. I wanted my legacy to be a body of work I created that was not compromised. I’ve learned that it’s more risky. It’s not guaranteed one will be paid after producing your own art, but in illustration, you’re paid — even if your work ends up not published.

What’s next for you, what medium would you really love to take a crack at? Are there any new projects on the horizon that you’re excited about?

I’ve collaborated with a band called Nightmare and the Cat. I paint while the band sings. I love the exchange that happens, responding to the music, or the musicians responding to the visuals.

I’m also collaborating with the designers of Frau Blau, based in Israel. We’re going to have an exhibition at the Holon Design Museum opening in May. Frau Blau is translating my art into fashion — and not just in traditional ways. The museum show will have more conceptual fashion artworks, but we hope to have wearable art in production and available soon.

Later in June, I’ll be re-creating “Giggle and Pop!” at the Culver City Artwalk. My Wild Girls and ChouChous will come to life, engaging with people and encouraging them to dance and play. I guess many of my new projects are more performative and participatory. It’s not just art hanging on a wall.

Walking Through Walls will be open at the Jonathan LeVine Gallery, 529 West 20th Street, 91 NYC 10011. The show closes April 2nd, 2011.

[…] Josh Sky – Read the full article on HEEB | […]