The filmmaker Joshua Safdie sat on the Walter Reader Theater’s stage. He looked to the ceiling as if the words that would form his next question were hidden somewhere in the rafters. A woman’s shrill voice from the seats interrupted his train of thought: “I’m sorry, can we just get back to Elliott Gould?!” The plebes were restless.

The event was a screening of Ingmar Bergman’s rarely shown The Touch from 1971. The film’s star, Elliot Gould, was in the house for a moderated discussion. It was showing as part of a series called “Hollywood’s Jew Wave,” curated by the Film Society of Lincoln Center and film critic J. Hoberman. The slate’s main conceit is that Hollywood films in the late 1960s and early 1970s featured an “unprecedented” amount of Jewish characters, actors and filmmakers. Other films on show were Annie Hall and The Apprenticeship of Duddy Kravitz.

Joshua and his brother Benny Safdie, whose 2010 Daddy Longlegs earned them critical praise, did their best to have a conversation with the Hollywood legend, but they underestimated the task at hand. They kept nudging Gould, trying to impress their own beliefs about his roles and his life upon him. They even thought David, the lecherous and violent archaeologist at the center of The Touch, represents some kind of a gruff, raw masculinity, a Jewish hero of sorts. “You’re wrong,” Gould insisted. They even meandered around whether or not his performance (in which he slaps, badmouths and emotionally tortures his paramour) was somewhat autobiographical, noting that he was still married to his first wife, Barbara Streisand, when the film was made.

The day before the screening I had the pleasure of speaking with Gould. Sitting there as the Safdies struggled to keep things together, I was tickled and somewhat relieved. I had already been through the experience of barreling through a conversation with him; it was nice to know I wasn’t the only one who had a rough go of it.

* * *

Elliot Gould typifies, perhaps more than any other actor of his generation, the dark, brooding, intellectual New York Jew that has become an archetype. He speaks carefully and with a Talmudic weight, so much so that even when he bounces around ideas incoherently, he comes across as sage-like. When I asked him his thoughts on the title “Jew Wave,” he surprised me. “I thought it was rather provocative. I was somewhat taken aback by it.” For me, a young Jewish cinephile who believes, who knows that there was a Jewish artistic renaissance around the fat middle of the last century, to hear Elliott Gould suggest such a title is a provocation, I am caught off guard. Stunned, really.

What is it then, I ask, that is provocative about it? “As funny as we are I don’t think it’s funny being a Jew. Who wants to flaunt anything? I think it’s difficult enough to be a Jew in this world and it always has been. I’m sensitive about it.”

I wander around the question again, pointing out that it seems there was a preponderance of Jewish characters, actors and filmmakers when he rose to fame. “No, no, no. I don’t think that way. I’m not terribly into categorizations and my belief is that fundamentally religion is discipline. And I believe in discipline. I certainly don’t want to actively provoke unnecessary reaction to what we Jews are which is a certain kind of human being related to the rest of us. I never want to be pretentious or assumptive or take anything for granted.”

I am now in Gould’s wilderness. The next thing that runs through my mind is “Oh shit, I’m not prepared.” All of my questions relate to him being among the first Jewish leading men. Though I would love to speak with him about roles from later in his career, rarely does the opportunity arise to ask about his earlier, and arguably more celebrated, work. I want to get to the bottom of this time period that I, and others, view as a great one for Semitic cinema. I thought, foolishly, this would be easy.

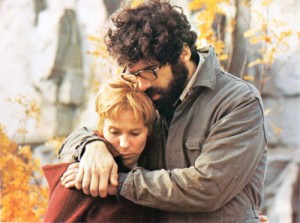

Elliott Gould and Bibi Andersson in The Touch, 1971.

“Jewish characters?” The phrase irks Gould when I use it in a sentence. “Character is character. You don’t have to be a Jew to have a character. A Jew has worked at it for a very long time, probably longer than most, by a thousand or some years, right?”

It isn’t long before he turns the tables and starts asking me a few questions to break uneasy silences. “Are your parents alive?” he wonders. They are. “Good.” I can only assume this is a reference to Philip Roth’s Portnoy’s Complaint which bears the quote “A Jewish man with parents alive is a fifteen-year-old boy…” You’re a pisher, he’s telling me, get on with it. Here I had a legend reciting the gospel of Roth to me, and yet he balks at referring to the late 1960s as the beginning of a surge of Jewish artistic contribution?

I start to wrap my head around Gould’s discomfort once I ask him about his work with Robert Altman. “Working with Robert Altman was a privilege for me; a relationship that developed into a very close fruitful, stimulating and creative relationship. He was in ways somewhat like my father. But he wasn’t Jewish.” No, he wasn’t. Their collaborations, including MASH, California Split and The Long Goodbye, were epic, on the fore of a new style of filmmaking that would push Hollywood forward. Not only was Altman not Jewish, Gould’s characters in those films weren’t either. If we believe Trapper John represents some kind of Hebraic ideal, that’s our problem. On the one hand, Gould is proud of his heritage, fully aware it is what makes him the star he is; on the other hand, to imply that he is successful only because he is a Jew is inaccurate, indeed it’s provocative.

“I’m extremely fulfilled,” Gould tells me, “but our work never stops. There’s one thing that I could never do and would never do is deny my roots.”

What would it be to deny his roots? He laughs at me when I pose the question. “I don’t know. It would be stupid. It’s not a possibility.” He then moves, in his own non-linear way, into a story about a role he didn’t get to do. “I was once asked if I would play Elie Cohen in a project called ‘Our Man in Damascus’ and Elie Cohen who was hung on television.” At this, he gets momentarily choked up, which he immediately replaces with nervous laughter. “He became the number one political guy in Syria. We know how we’re hated and how we’re resented and how a great part of the world would rather we not be here.”

Even when I try to lighten things up and move to other questions, he wants to return to Judaism. I get the feeling he has thoughts he wants to get off his chest. “I couldn’t have imagined or believed that one like this, like me, Elliott Goldstein from 6801 Bay Parkway, Brooklyn, New York, could get to the front and participate and contribute, and I’m there. It’s taken me forever to get here and I want to know that I’m giving everything.”

I mention, cautiously, it doesn’t seem like it was hard for a Jew to get work in Hollywood. “Not hard for a Jew to get work in Hollywood?!” Our people, I mention, have a long history in the movie business. “That doesn’t mean it wasn’t hard! Generally speaking, no one gave us anything on a silver platter. We had to work for it. We had to succeed to continue and we still do.”

When I ask him how Jews still have to work hard to get ahead, he tries to answer, but the truth is that there is no sufficient answer. As he told me earlier, character is character.

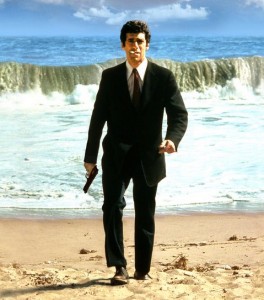

The Long Goodbye, 1973

Before we part ways, Gould has a few more words on his Jewish identity he would like to share with me. “Being an idealist it was difficult for me to be brought up by people who would be practicing a religion and didn’t believe. I love to believe. But then I realized that for me, the concept of God is the ultimate ideal. Yeah, I accept! Sometimes, I think if I knew what this world was about before I embarked on this apparent career that I might have gone in a totally other direction and studied more and learned more and been Ultra-Orthodox and even Hasidic. But I’m not.”

I tell him he is speaking passionately, offering answers coming from a deeper place than I expected when we set up the interview. “There’s a lot going on in my life right now and so I’m very open. You can obviously hear it. I appreciate it, therefore it’s a privilege for me to share this because I share it in my work and I share it abstractly; I’ve never explained some of these things.”

I wonder whether or not our conversation isn’t just another abstraction. After a prolific (and continuing) career, it’s difficult to see where Elliott Gould ends and his work begins. He bit back at Josh and Benny Safdie at the Bergman screening because they were taking their own life experience and saddling it onto him. He doesn’t see things that way. When I asked Gould a question about his cameo in Nashville, he got sentimental. “It moves me because this is all a part of my life and my work.” We get to live vicariously through his characters. He has no such luxury.

Our interview ended a few minutes before I realized he was done talking to me. I’m not sure what else I could even ask, so puts a sticker on the thing. “I’m talking from my heart and I’m vulnerable but I don’t want to tell any more stories right now. What more do you want me to say?”

“relate to him being among the first Jewish leading men”

An offensively wrong statement. The first Jewish leading man was of course the first leading man, period. Look up Broncho Billy Anderson. After that there were Edward G. Robinson, Kirk Douglas, John Garfield, Tony Curtis, Cornel Wilde, Jean-Pierre Aumont, Laurence Harvey, Walter Matthau, Paul Muni (the first Jew to win Best Actor, for 1936), Ricardo Cortez, Gene Barry, Jeff Chandler, and on and on. This was way before the 1960s, much less the 1970s. I’m not that familiar with those early decades of cinema, and I could still come up with this list. In fact, I would imagine that the golden age of Jewish leading men – the 1950s, with Douglas, Curtis, and the “half Jewish” Paul Newman – will probably never be replicated again.

The whole 1970s “Jewish” thing is just an anti-Semitic canard, where the implication is that if you’re not some kind of New York stereotype like some of Gould’s characters, you’re not really Jewish. I can find no other explanation for its existence, but this story is blatantly false and needs to go away forever.

My late father, Shimon Wincelberg, was the first Orthodox writer in Hollywood, and he used to tell a story about his first experience in Hollywood, which could also have been his last. And it echoes what Mr. Gould says about it not having been easy to be a Jew.

My father was summoned to meet with Zanuck — on a Friday night. My father told Zanuck’s disconcerted assistant that he couldn’t meet on Friday night because it was the Sabbath. She didn’t want to bring the news to Mr. Zanuck, to whom no one said ‘no.’

After hanging up the phone, my father turned to my mother and said, “We might as well stop unpacking and move back to NY. I’ve just destroyed my career in Hollywood.”

But surprisingly, the phone rang a few minutes later; it was Zanuck’s secretary, this time asking, “Would it be ‘convenient’ for you to meet with Mr. Zanuck on Sunday?” My father’s point was that people respected others who had the strength of their convictions and didn’t complain about the fact that their religion ‘prevented’ them from doing something they wanted to do.

My father once got a call from an actor who was required to film a scene on the Sabbath, and didn’t know what to do. My father asked, “How much would it cost to film on Sunday, instead.” The actor replied, “$10,000.” My father said, “Then tell them you’ll pay $10,000 to film on Sunday, instead.” The director realized the actor was serious about not being able to film on Saturday, and changed the filming schedule.

Of course, my father occasionally liked to go out of his way to emphasize his ‘Jewishness.’ Also early in his career, when someone (an agent?) recommended that he change his first name because Simon sounded “too Jewish.” He agreed, and changed it to ‘Shimon.’

In spite of this, Mr. Gould is also right that there are plenty of people who would be happy to see Jews gone from Hollywood, just as many would like us to see us gone from Wall Street, medicine and law (all professions that Jews wound up in because they were prevented from being in the metalworking and woodworking guilds back in the 1600s).

I somewhat agree with Portisky that Elliott Gould was ‘the first Jewish leading man’ in that Gould pays honor to his Jewishness through his roles, in such a way that Hollywood never had any Jewish actors do before.

When Dee writes that the ‘whole 1970’s Jewish thing is ‘just an anti-semitic canard’, that sounds a little self-hating. As a non-Jew I love the whole New York Jewish ambience in film, and Gould was and is a great representative for that. Celebrate Yiddishkeit!

So the “first black leading man” is only black if they “honor” their blackness in their roles? And how would they go about doing that?

“pays honor to his Jewishness through his roles, in such a way that Hollywood never had any Jewish actors do before”

-No, wrong again. I’m not sure what “Jewishness” Gould “honored” in his films (New York accent don’t count, sorry), but I’m pretty sure Paul Newman and Kirk Douglas’s characters in Exodus and Cast a Giant Shadow, respectively, helping found Israel, would trump whatever it is he did.