Art is always a foray into a new frontier, and it is especially fascinating when both artist and subject do it in tandem. Such is the case of cartoonist Miss Lasko-Gross‘ third graphic novel Henni, a bildungsroman with the shadowed heart and blue wash of a Hans Christian Andersen fairy tale and the surety of a call-to-arms. Lasko-Gross’ latest — the story of the titular character Henni, an anthropomorphized cat who comes of age in a restrictive religious society and seeks her freedom from it — is a departure from her two previous novels, Escape from “Special” and A Mess of Everything, both heavily steeped in the autobiographical turmoil and eventual punk-flavored liberation of growing up as an outsider in Newton, Massachusetts. HEEB sat down with Lasko-Gross to talk about Henni and what makes her the pitch-perfect voice from the periphery.

*****

How did you get into graphic novels and drawing cartoons?

I loved to read them as a little girl. They always spoke to me more than just traditional literature or even traditional art, the way you could get enveloped in a story. In particular, I loved Love and Rockets and Tank Girl and Akira. Those were stories that always enraptured me.

[Drawing cartoons] was a way to express myself, to make comics for revenge. I don’t know if that’s a way a lot of people get into it. But for someone who feels like they don’t have a voice, It was great to have an entire world where you felt like the G-d, that you are in fact right about everything and that everyone else is wrong. So that was my very juvenile reason for beginning comics. That was around sixth grade.

I started doing it professionally when I was in high school. I distributed through the zine network — this was the 90s. I would take them around to stores and create a small network through zines and trading, selling on consignment.

What did you mean by “making comics for revenge”?

In school, if you’re someone who never gets to have their say, or if you’re not listened to in particular…well, you find your own ways of fighting back. There were some mean and bitchy girls [I went to school with], and it was just great to create a comic where I could just show them all the piss and vinegar that they’re filled with — you know, to expose them. As opposed to in the real world, where they’re “right,” and no one is going to listen to you or see things your way. So I guess it was about a sense of control.

Did you feel a sense of disenfranchisement growing up?

Did you feel a sense of disenfranchisement growing up?

I felt that nobody got me. Everyone feels that way on a level, especially during their surly teenage years, but I was actually somewhat justified.

I was helping my parents clean their house a few years ago, and I found a bunch of progress reports that were done on me as a kid. I don’t know if you’ve read A Mess of Everything or Escape from “Special”, but I was a special ed. student and seen as a problem. I was just different from everyone. But they bounced me from public schools to private schools since kindergarten anyway. When I looked a those reports, I just thought, “Man, they really didn’t get me.”

Do you think your Jewishness was a part of that?

In my Jewish liberal suburb, I was still seen as a weirdo, which should tell you something. I didn’t feel like an outsider as much as I should’ve — in Newton, [Massachusetts], which is like fifty percent Jewish or something, I assumed until an embarrassingly late age that fifty percent of America was Jewish, and fifty percent was Christian. So I don’t know if being Jewish makes me feel like an outsider — I think I fit into the tradition of a shameless, self-examining, Jewish auto-bio cartoonist.

How did you come up with the idea for Henni?

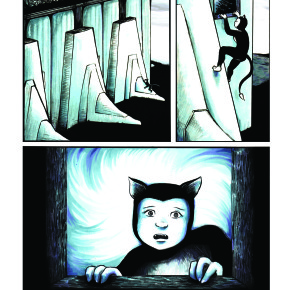

Henni was a side project. At the time, I was working on what was in retrospect a very misguided nonfiction graphic novel, and Henni was something I did for my own sense of pleasure. I thought of what kind of story I like to read, and I was like, “Okay, an adventure story! There’s a girl, this cat, and she’s moving through a landscape, and I’ll kind of just make it up as I go along.”

Very quickly, it spiraled out of my mind, way ahead of what I was drawing. All of a sudden there was this almost-psychic story to tell. Eventually, I saw that [Henni] was where my passion was at the time, so I switched over [from what I was originally working on] and made that my project. I had to go back and re-draw some of the stuff I had done — just to make it a little more stream-of-consciousness. But [Henni] was a story which just bloomed in my mind like a weed.

What is your process?

What is your process?

I have a “crazy person” process. I know how it begins, and I have a sense of a few things that have to happen in the middle — key points for the story — but I never write out a really tight script. I feel like the art half of me gets screwed over by the writer half of me if I do that. As I’m drawing [key points], I can let it flow as long as I get to all the points on the map, so to speak. I’ll do about four or five pages at a time. So that’s how a crazy person works — that’s not how you’re supposed to do comics.

What made you want to set Henni’s world in the world that she ended up in, and what made you want to anthropomorphize the characters? I know it sounds kind of cliché, but the closest comparison I can think of where that is utilized is Art Spiegelman’s Maus. Was there a specific purpose to doing that?

I think that characters who are not human free you up a bit to tell stories which otherwise make people tense up, get defensive, and put up walls — because I’m insidious like that! [Laughs].

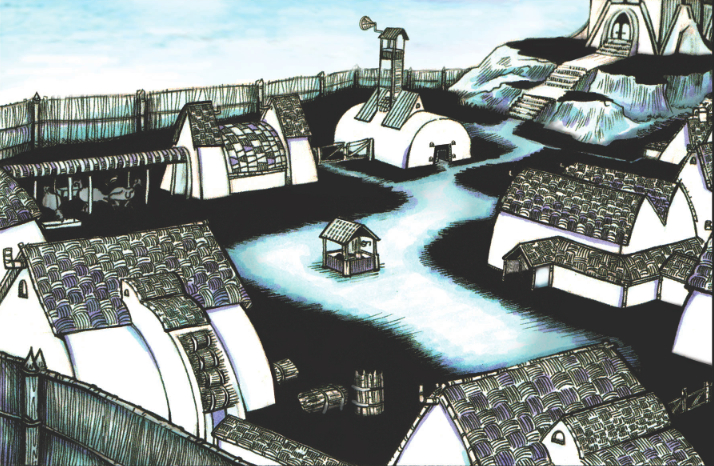

In Henni [the characters’ species] are intentionally obscure — I didn’t want anyone to possibly be able to ascribe their [respective species] to groups, like, “these are the Christians, these ones are the Jews, here are the Muslims,” like something comparable to what Art Spiegelman does in Maus, with the Jews and the Nazis and Polish people. Every culture and every place is a mash-up of at least three different cultures for a reason. It should feel very familiar but unplaceable. A little bit of medieval Europe, a little of Victorian England, a little of Calcutta, a little of Hong Kong, a little bit of a bunch of different cultural traditions.

Having these characters that are somewhat familiar but not human gives me the ambiguity to discuss things that are sensitive in a way where no one makes the mistake of feeling personally attacked, and therefore taking them out of the story and the enjoyment of the adventure.

*****

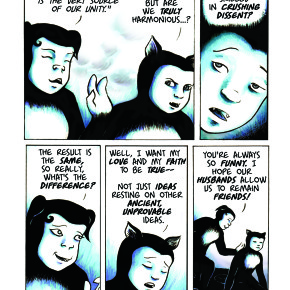

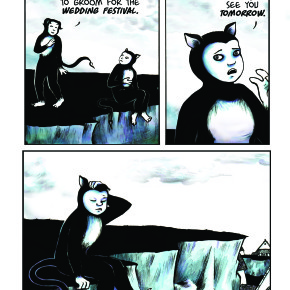

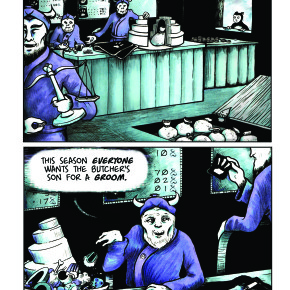

HEEB Exclusive Look at Henni

*****

The hypocrisy of organized religion, feminism, and coming to a sense of awareness about the world as a whole — especially regarding Henni — are all huge themes in your book. Do you go into the project with incorporating these themes in mind?

I never set out to teach people about something — being didactic is the last thing you want to do when you want to captivate and entertain people. So I think those themes [feminism, religious hypocrisy, etc.] are so close to my heart that all I have to do is create the world and the society, and the themes organically spring up. They’re just as a part of me [as] my worldview. Any kind of commentary on our world wouldn’t be complete without those themes.

One of the common threads that weave our “beautiful” tapestry of respective world religions together is that they mostly treat women like crap; [in Henni] I tried to come up with various reason why God would want that. By any name, it’s complete bullshit. While Henni does discuss that, it’s not about teaching people anything — it’s something that everyone already knows, even if they haven’t intellectualized it, or vocalized it, You just need to look at what’s going on in the world. Like look at BBC News — just pull it open and take a global look at the news — and those themes are right in your face! They’re easier for us to ignore here in the U.S., where we live in a pocket of relative comfort and egalitarianism, but globally, that’s not the case.

Do you think you instill a sense of autobiography in any of the characters in Henni?

Do you think you instill a sense of autobiography in any of the characters in Henni?

Absolutely. Henni is very different from who I am, but when I imagine myself in her circumstances…

I mean, Henni is nicer than me, more mild-mannered, but she’s torn between what she has been taught and what she witnesses in the world. [In] my autobiographical work, you know I’m not a fan of organized religion. I rejected it from a very early age. Henni doesn’t have the luxury of that. There’s no alternative or escape, even among her friends or among her family. There is no one who is willing to have an open dialogue of any kind or any other alternate viewpoint. Even her father, a militant atheist who she loves very much, is taken out of the picture very early on in her life and disposed of by the church — the Temple, rather [in the book]. So she doesn’t have any other influence or anyone to talk to, except for her mom, who is an ardent supporter of the Temple. I feel a great amount of sympathy for her situation.

[But] I don’t think there’s any characters that are like myself. Maybe the Disruptor [a renegade artist who was blinded when he dissented from his society]. Anyone who is in Henni’s circumstances would like to think that they could be that brave. I don’t know if I necessarily would, though.

You have some strong, much-vocalized views on organized religion that also feature heavily in Henni. How did you come to them?

I’ve asked myself that. The rest of my family managed to retain their Jewish faith. Like my sister — she’s the “good Jew,” she does all the traditions and “magic” and stuff. [Laughs.]

I think it was a combination of the reading material I read as a kid — Greek mythology, fables, all kinds of mythology and folklore from different cultures — and I think reading all of those in tandem coalesced into the idea that they were, well, kind of all the same thing, so it’s kind of all crap. It was all so controlling! I felt like religion was trying to control me — and really, I have no idea how I came to that conclusion at such a young age. But my parents didn’t indoctrinate me [into observant religious Judaism] at a very young age, and I think if they don’t indoctrinate you at a young age, everything related to religion becomes an absurdity. If I were to tell you about a set of people that believes that their messiah was a giant hippo, and will one day deliver them to a land of candy and happiness, that would sound crazy to you, because you weren’t raised to believe in a giant flying hippo messiah. But if that was your thing, how you were raised, you would accept that.

When I was younger, my dad was in a band and they went on tour, and my family went along with him. We stayed in an ashram and were told we couldn’t sit in the guru’s chair. We got in a lot of trouble because I wanted to sit on the guru’s chair, and I did! So there’s also the possibility that I’m just an asshole. [Laughs.] Because no one else was allowed to have the chair! Everyone else sat on the floor, and there was that one chair, and I didn’t want to sit on the floor. So I’m only half-kidding when I say I’m an asshole — [my views are] a matter of attitude and too much reading material.

Do you consider yourself a Jewish writer?

Do you consider yourself a Jewish writer?

I consider myself a Jewish writer/artist/graphic novelist. Regardless of lack of faith, I’m such a Jew. I feel that so strongly because my husband is Catholic, so just by comparison, my “Jewness” is a presence in my life. If we can spend a reasonable amount of money on something or a crazy amount of money on something, you can guess who comes down where, in so many cliche ways. [Laughs]

But being a Jewish writer does not define me wholly as an artist — it’s not my primary categorization. I would probably put “woman” before “Jewish”. My Jewishness doesn’t really define who I am, but it definitely flavors my work. So if I just said one or the other — Jewish or not Jewish — it would be disingenuous.

Define “Jewish flavoring.”

When I talk about “Jewish flavoring,” I don’t mean it in the religious sense. [Growing up,] if I could present a good case and argue my way out of whatever it was I didn’t want to do — you know, be reasonable and discuss things — it was fine. But in my Gentile friends’ homes, explanations weren’t given — it was all, “because I say so,” or “because that’s the rule.” There’s more of a push back in Jewish culture — asking questions or wanting knowledge, wanting to push the rules a bit. Just a little less obedience is expected. You’re expected to be smart and inquisitive, and that’s valued so highly that you can get away with stuff that most people in an authoritarian household wouldn’t.

In a lot of Jewish literature and art, marginality is a theme that is often invoked. Do you identify with that, especially regarding your work and your status as an artist?

Being outsider affects how I view the world tremendously. The most significant thing about being a Jewish writer or artist is that no matter what, you’re going to be an outsider. You can forget at times in your bubble of safety — like living in Manhattan — that you’re more accepted here than you would be anywhere else, [and] at this time in history, in this place, is the best time to be a Jewish woman cartoonist.

It helps to see the world more clearly, to always be on the outside, just on the periphery of “normal.” Having that small bit of distance affects how I make my art and how I comment on the culture. I don’t say that in a mopey, sad way; it’s just something I’m aware of in the back of my mind. And I can always use it to my advantage.

This interview was cut and edited for clarification. All Art Used With Permission (c) Miss Lasko-Gross.

Leave a Reply