Jewdar presumes Hannah Arendt was actually a chain-smoker, which makes the constant lighting up in the new biopic Hannah Arendt by both her and everyone around her understandable, but it’s still hard to watch things like that in the wake of Mad Men and not have a feeling that “aha, the filmmaker wants us to know that this is the 1960’s.”

Jewdar presumes Hannah Arendt was actually a chain-smoker, which makes the constant lighting up in the new biopic Hannah Arendt by both her and everyone around her understandable, but it’s still hard to watch things like that in the wake of Mad Men and not have a feeling that “aha, the filmmaker wants us to know that this is the 1960’s.”

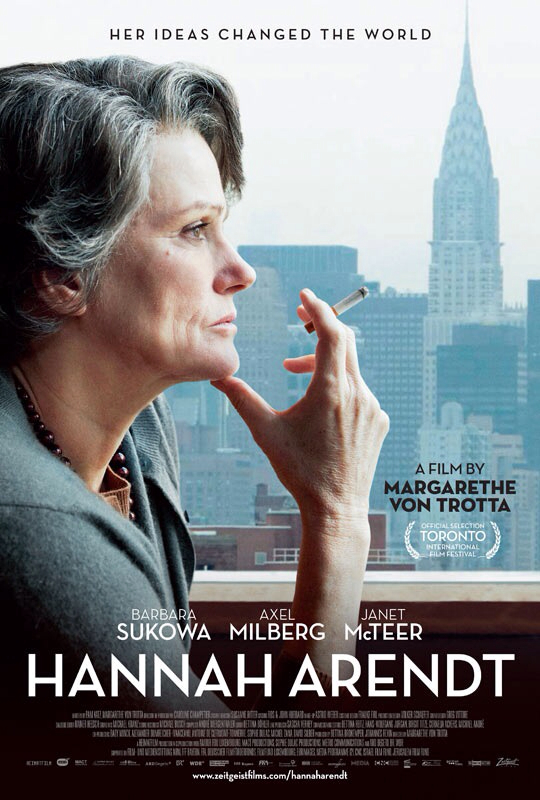

This, by itself, is not so terrible, but it illustrates what was for Jewdar one of the central problems of the movie, which is that the writer-director Margarethe von Trotta (presumably no relation to the fictional von Trottas–see, Jewdar’s not a complete imbecile) wants us to feel things in a way that too often is both blunt, and not entirely true.

The movie is set in the period of the Eichmann trial (spoiler alert–Eichmann is found guilty), in which professional intellectual Arendt heads off to Jerusalem to cover the trial, writes about it, and gets into all kinds of hot water for her provocative statements regarding the “banality of evil” and the accusation that Europe’s Jewish leadership played an important, necessary, and collaborative role in the catastrophe that befell European Jewry just a decade and a half earlier. What’s interesting is that while the movie is all art-housy and talkie, at its root, it’s an action film. The problem is that the action is all art-housy and talkie.

Instead of bullets flying, we have words, as Arendt and her circle of German expats debate endlessly on the nature of evil, and the justice of trying Eichmann, and the justice of executing Eichmman, and the question of tribal loyalties and all manner of other things. Instead of a machine gun, we get a lot of scenes of Arendt furiously pounding away at her typewriter. Instead of cheesy sex scenes, we have lots of shots of people looking admiringly at each other –Arendt and her husband make googly eyes at one another, Hannah’s students make googly eyes at her, in flashbacks she makes googly eyes at Martin Heidegger, when she goes to Israel, she makes googly eyes at her old friend Kurt Blumenfeld who makes googly eyes back at her. We get it, she’s awesome. Und so brave, und so independent… und so vhat?

The action film even has a big shoot-out at the end, except that instead of explosions, we have an impassioned (well, as passionate as Arendt gets) speech. And here’s the thing–movies that have as their crescendo a big impassioned speech can work, but there has to be something serious at stake (like whether or not Kevin Bacon can dance in Footloose). But one big issue with this movie is that for all the efforts to make this seem dramatic, there’s very little that seems to be at risk. Even in her big final confrontation, there doesn’t seem to be much of a worst case scenario. What if she didn’t make her speech? What if her speech wasn’t that great? It’s really not clear that she would suffer anything more than personal indignation. We viewers aren’t really given much reason to really worry about Arendt, and–here’s where Jewdar gets a bit nerdy–I don’t know that we should. Because, for all the courage, and outspokenness and willingness to stand up for her beliefs on the big issues, she was either wrong, or oversimplifying things (don’t get me wrong–people have a right to be wrong-and Jewdar has a certain sympathy for people wrongfully accused of being a self-hating Jew–but again, it’s unclear that she was actually going to suffer much professionally for her wrongness)

Let’s start with the “wrong.” Arendt’s views on the “Banality of evil” drew great attention, and have intrigued generations. The problem is that, at least when it comes to Eichmann, she fell for his act, hook, line and sinker. Eichmann was not simply some faceless bureaucratic drone who would have been just as happy to be shipping widgets as transporting Jews to their death. He was an enthusiastic Nazi who embraced his task and pursued it with great vigor. He joined the Nazi Party in 1932–the Austrian Nazi Party. Meaning that he wasn’t some opportunist who joined just to get ahead; he joined before Hitler took power in Germany, and long before taking power in Austria even seemed like a possibility. And he didn’t just join the party, He joined the SS as well, and in 1934, having moved to Germany (another bit of initiative on his part), he joined the SD (the SS security service) and later transferred to the Jewish Department, rising up to be Reinhard Heydrich’s Girl-Friday. Far from simply following orders, he enthusiastically pursued his tasks. The man in the glass box in 1962 may have been a figure faceless banality, but back in the 1940’s when it was time to put the screws on the Hungarians to turn over their Jews, Gestapo Chief Heinrich Mueller sent the man he referred to as “The Master.” Evil, yes; Banal, no.

As for oversimplifying, much of the film’s dramatic conflict comes in response to statements she made referring to the role played by the Jewish leadership in facilitating the Holocaust. The problem with her critique, while of course having some kernel of truth, is that it was the kind of facile moral clarity that was easy to find in 1960’s Manhattan; Things were not quite so clear in Eastern Europe during the war. Had Arendt limited herself to making specific accusations against specific individuals, it would have been one thing, but while she allowed for some nuance, she painted with a broad brush. While there were no shortage of Jewish leaders who worked to save themselves or their families, there were many others who found themselves making impossible decisions in impossible situations. Jewish leaders had always been forced to make accommodations with the powers that be, and on one level, the head of a ghetto in 1941 was acting no differently than his predecessors had done in ghettos in 1841 or 1741. Arendt is perhaps right that without Jews helping to organize the ghettos, the deportations from the ghettos might have been much harder; on the other hand, without those same Jewish leaders having organized the ghettos in the first place, the Jews in the ghettos would have starved to death two years earlier since the Germans wouldn’t have been providing rations.

The movie does have it’s good points–most notably the depiction of a young Norman Podhoretz as Greg Marmalard–but ultimately, it’s a film as unsatisfying as the depiction of Arendt’s postwar confrontation with her mentor/lover/Nazi Heidegger, in which Arendt can’t bring herself to really emotionally challenge his own betrayal of both his principles and of her. That scene more or less encapsulates the movie–we’re supposed to believe that there’s something powerful and important going on, but there’s not enough on the screen for us to really to get worked up about it.

Seems a fair review. My main issue with Arendt is that she

believed that the Jews were too passive and went like meek sheep to

their deaths etc etc. Aside from the known instances of resistance,

and aside from the fact that all too often the Jews were led to

believe that they were merely being relocated, there is the simple

fact that old men, young children, teens unarmed could do much to

resist an armed SS and German military. I had been in Korea, and

had seen, firsthand, lines of North Korean and Chinese

POWs–trained fighters being marched Soutward to prison camps.

There were very few guards and it would have been easy to break and

run. Run where? If trained military were so “passive,” then what to

expect from Jews rounded up ? H.A. had the advantage of not being

in the situation where she had a choice to resist, and so it was,

for me, simply an arrogance on her part to indict a people as she

had done.

I agree with a lot of what you see; I think that rather than taking umbrage at the whole “like sheep to the slaughter” thing, though, the second part is more instructive. For the most part, Jews did go where they were told, but like you point out, that wasn’t unusual. You don’t even have to look to Korea–look at Katyn and the other Polish officers murdered. “Like sheep to the slaughter,” they knelt down, and let someone put a bullet in the of their heads. Most Jews did go like sheep to the slaughter, but, as you note, there were often other factors, and Jews were hardly alone in this. Like I said, judgments are easy to make from the comfort and safety of decades and distance.

Arendt’s point about the “banality” of the “banality of evil” part is not dependent on Eichmann being a passionate anti-Semite or not. Her point was about the new technologies of mechanized killing, the bureaucratic forms of managing destruction, and how responsibility and agency are deferred in those management structures. See 289-290 of Eichmann in Jerusalem for this. She mentions “banality of evil” once, in relation to Eichmann’s cliche joke of a final speech before being hung. In her misreading of Eichmann’s character she still discerned something important in the structure of totalitarianism (and perhaps modern systems) that holds true. These truths were used to assess the distance killing of the Vietnam war, and at the first Arendt conference held in Jerusalem, in 1997, which I attended, some Israelis noted the lessons for those compliant, or even encouraging, of the Occupation of Palestinians, only a few miles from our conference. The virtue of the movie is that now a lot of moviegoers will be interested in reading Arendt, one of the great thinkers of the 20th century.

Books are full of complicated words that I can’t understand, I was writing a movie review, and the movie certainly dwelt at some length on her reading of Eichmann’s character. I still think X-Men First Class was a far more interesting account of one German Jew’s efforts to comprehend and cope with the ramifications of the Holocaust than this movie. Come one Eliot, that scene in Argentina with Magneto? Admit it, it was awesome.

Dave, I was so looking forward to seeing this movie, but have burst my bubble. I was hoping it would show in detail how young Arendt was swept off her feet by Marty, how she actually helped Jews get to Palestine before she got out of Europe, and perhaps how her loser buddy Benjamin offed himself. Also it sounds like it does not focus much on her book On Revolution, which I would take in a New York Minute over Eichmann in Jerusalem. Oh, well. I guess I’ll just have to keep waiting for another movie.

Adam–presuming this is who I think it is–this is doubtlessly not the first time that something I’ve said disappointed you, but the first time in decades, so that’s something.