Let Jewdar begin by saying that, as someone whose laziness and lack of direction killed his highly unpromising future as an academic, it gives us great pleasure to be able to review a work like Choosing Yiddish: New Frontiers of Language and Culture. Edited by Lara Rabinovitch, Shiri Goren, and Hannah S Pressman, the book is chock full of the kind of cutting-edge work in Yiddish Studies that a more diligent Jewdar might have done, but now, these tenured wonks are desperate for a few words of praise from Jew-Know-Who. Of course, Jewdar, like every critic, has a part of us that wants to pan those who produce the works we know we’re not capable of, but thankfully for the assorted authors and editors, Jewdar is too honest and honorable to go down that path. So short review, we liked it overall, and particularly enjoyed certain studies.

Let Jewdar begin by saying that, as someone whose laziness and lack of direction killed his highly unpromising future as an academic, it gives us great pleasure to be able to review a work like Choosing Yiddish: New Frontiers of Language and Culture. Edited by Lara Rabinovitch, Shiri Goren, and Hannah S Pressman, the book is chock full of the kind of cutting-edge work in Yiddish Studies that a more diligent Jewdar might have done, but now, these tenured wonks are desperate for a few words of praise from Jew-Know-Who. Of course, Jewdar, like every critic, has a part of us that wants to pan those who produce the works we know we’re not capable of, but thankfully for the assorted authors and editors, Jewdar is too honest and honorable to go down that path. So short review, we liked it overall, and particularly enjoyed certain studies.

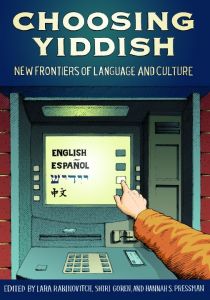

Longer review, we’d like to say that Choosing Yiddish is a bit deceptive, right from the cover. This is not a book about the modern Yiddish speaking community (which, in some places, actually has Yiddish-language ATMs), nor, on one level, is it even about Yiddish. Rather, it’s about Yiddish Studies, and the wondrous places that it can take the curious. Jewdar may sound glib or dismissive, but that’s just your cynicism–Jewdar loves him some curiosities of Yiddish Studies. The book is, to some extent, a showcase for the discipline, highlighting the remarkably broad array of fields though which a Yiddish scholar might spatzier. As that suggests, there are going to be some trips more interesting than others, and some places that you wish they’d dallied a little longer.

Eddie Portnoy, as always, is entertaining, with his look at a scandalous Hasidic murder trial in 1870’s New York. Jewdar’s also a big fan of Anna Shternshis’ Soviet and Kosher, and she doesn’t disappoint with her study of Yiddish and Soviet-era nostalgia. And Ester Basya Vaisman’s examination of the ways in which Hasidic women relate to Yiddish songs looks into that great Yiddishist taboo (more later), Hasidic Yiddish. Others offer little treats (okay, Jewdar is a nerd, so sue us), like Rebecca Kobrin’s insight into the way that Jewish immigrants in New York and Buenos Aires rallied behind the new Polish Republic in the interwar period–a bittersweet reminder of what could have been. Also, we couldn’t help but feel, while reading Tony Michels account of WASPish fellow travelers at the turn of the century getting street-cred by slumming with Jewish radicals on the LES and digging on their “authenticity,” that some of those Jews’ own thoroughly embourgeoised grandkids would probably do the same thing 60 years later with African-American civil rights activists and black nationalists.

To be sure, there were some that left us unmoved (note to future editors of Yiddish Studies collections–Jewdar doesn’t understand numbers very well, so when you have the words “Beta Values: Standardized Coefficients,” you’ve lost us). More importantly, we never really shook the feeling that we’d been deceived.

Let’s begin by noting that what is about to follow is perhaps more a reflection of Jewdar’s own lunacy than any actual deficit of the book, but we are aware of the hostility many in the Yiddishist world bear for Hasidic Yiddish (ironically,viewing it not terribly different from the way all Yiddish was viewed by maskilim and Hebraists–as a jargon, not a language). Consequently, there is a tendency to write about Yiddish and its future without a whole lot of reference to the largest and most important Yiddish speaking community in the world. The Yiddish ATM on the cover is used simply as a conversation starter about a whole lot of other things–but not the Hasidic communities that actually make use of such things. Vaisman’s piece was nice, but even there, much of it dealt with the way younger Hasidic women deal with older Yiddish culture, and not the ways that Yiddish is used in the Hasidic world today.

But this, as noted, is more Jewdar’s own narishkeyt than anything else, and if we start down the path of evaluating books for what they leave out rather than what they put in, all those authors who don’t have gripping depictions of Jewdar mowing down Nazis at Normandy with the 101st Airborne Division have a lot of ‘splaining to do. Last words we’ll give are actually some of the first words the book has, from the foreword by Barbara Kirshenblatt-Gimblett, who calls for a new field of Ashkenaz Studies that would incorporate the totality of the Ashkenazi Experience in Europe and abroad. How can a guy named Jewdar not give his hechsher to that, and to a book that is part of that project?

*****

Leave a Reply