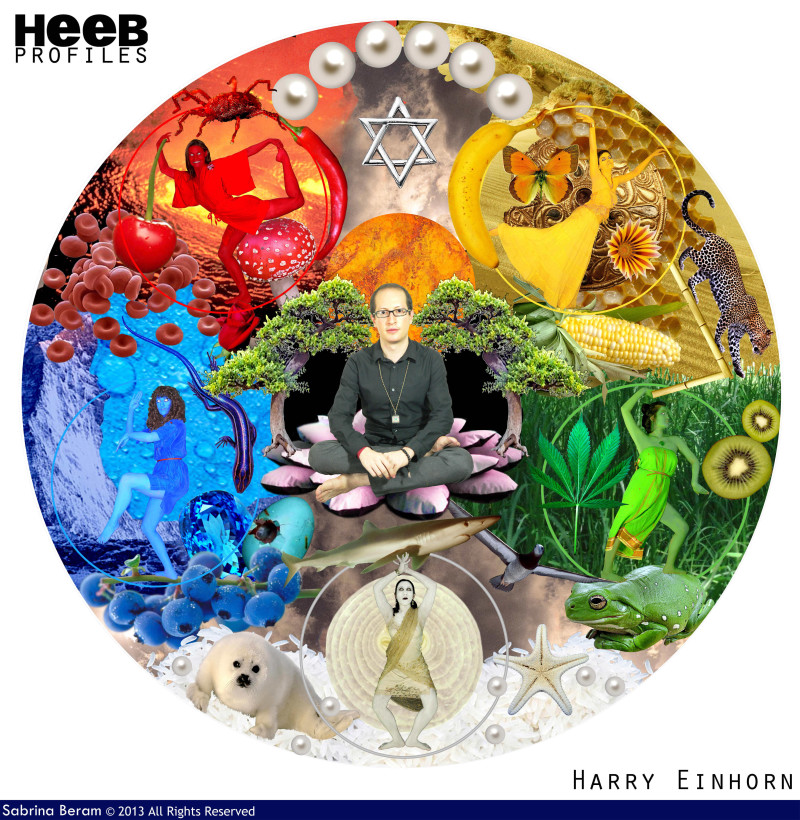

When Harry Met Buddha

Five women wearing red, white, green, blue and beige walk in to the middle of the room in front of soothing patterns projected on the back wall. Rhythmic a cappella chants can be heard as an interpretive dance, symbolizing space, compassion and harmony, begins. This is Harry Einhorn’s Buddhist meditation, brought from India to Brooklyn through his new show, Samaya.

Watching this experimental performance, it dawned on me that what little I knew about Buddhism was based primarily in my sixth grade history class. Yet, in spite of a Buddhist background as week as mine, I connected. Immersed in the open culture and ideology of Buddhism in this completely sensory way, it was hard not to let the bustle of my mind fall to it’s knees.

Bursting back to the New York scene after an eight month education in India, Einhorn was ripe with ideas for a theatrical interpretation of his spiritual journey. Growing up in a Canadian Buddhist community, themes of balance and compassion were instilled in Harry at an early age. It was New York’s particular flavor of narcissism – particularly that of Brooklyn’s hipster scene – which awakened a deep desire to re-engage with these ideals. Following the Buddha’s example, Harry went public with his teachings in hopes of eliminating ignorance and suffering by increasing understanding.

Except from Samaya’s manifesto, “Calling the Gurus”:

“We are surrounded by war, famine, disease

Rampant materialism

Dysfunction; aggression; pain

And continue hiding in our cocoons

We are blown about by the fierce winds of our thoughts and emotions

Never giving a chance to stop and examine them.

Instead, we continue to distract ourselves with gadgets

[…]

Though our true nature is right in front of us,

We do not see it.

Several days after Samaya’s final performance, Harry and I sat down to talk. Twisting his hands into dynamic Hindi gestures, he comes across as a whimsical storybook character- a sign of his deep submergence in performance art. Wanting to get to the root of his Buddhist obsession, we launched into background of his parents attraction to Chogyam Trungpa Rinpoche, the first teacher of Tibetan Buddism in English, who fled to India in 1959 with the Dalai Lama. As our teacups emptied and refilled, the conversation flowed about growing up JewBu, nonlinear art, and how Buddhism can help ease neuroticism.

*****

How did Judaism and Buddhism play out together for your family?

Meditation was something that people did. Some of the fundamental ideas told to me when I was a kid were that everything is impermanent and in life one can expect suffering. But we would always do Passover and Hanukkah and I grew up saying those prayers in Hebrew.

Holidays are one thing, the Jewish mentality is another. Why were the Jews attracted to Buddhism?

As far as I know, from the very beginning of a greater Buddhist presence in America there have been a disproportionate amount of Jews studying and practicing. This started with the Beats in the 50s with their interest in Zen and continued into the 60s and 70s with the arrival of Tibetan Buddhism. My background and ethnicity is Jewish, my practice is Buddhism. They exist together and neither has to break off or become it’s own thing– there’s no disagreement or conflict. Buddhism welcomes the kind of intellectual questioning, logic, and skepticism that I think are part of Jewish culture. But from a Buddhist perspective, anything that solidifies an “identity” is fishy anyways!

Is there no Jewish brand of buddhism?

To self consciously posit a “Jewish brand” of Buddhism is just creating more separation, which is not really necessary. We have enough separation already. Wisdom and compassion, by their nature, do not discriminate between jews, gentiles, animals, insects, etc. We all have the capacity to wake ourselves out of delusion.

Buddhism dissipated in your family by the time you were a teenager. When did you reconnect?

I went to Northwestern for Musical Theatre. I didn’t like it (I was very emotionally awkward, I had a lot of social anxiety) and sophomore year I began to meditate because I was so miserable. I got a book called Mahamudra by Trolley Rinpache. I started sitting for five minutes every day thinking, ‘OK, let’s start working with my mind.’ It didn’t alleviate my suffering but it started giving me a taste of what it was like to be introspective, to look within.

When did you start creating performance pieces based on Buddhist themes?

I met [my writing partner] Philippe Treuille senior year of college and we did a movement theatre piece based on the Buddhist Wheel of Life, which illustrates the cycle of suffering and different realms and rebirth.

On your return from eight months of learning Tibetan in India, you began efforts to create your show Samaya. Why?

When I came back I was so inspired. I saw monks dancing and I saw their rituals. I see it is as an expression of the richness of their tradition and as an appreciation of what they have inherited. Some of the music for Samaya I was hearing in my head while I was India. I said I couldn’t not create this piece anymore. I’ve personally experienced a transformation from extreme neuroticism and misery to a more open, spacious state of mind with less suffering. I wanted to introduce people to the idea of the mind and wanting to spread goodness, harmony, balance. These teachings are so precious to me. I slept on my grandma’s couch and all of the money I made went into the show.

Harry’s entourage of Dakini dancers.

Tell me about the women performers, the projections on the wall, the music.

The show takes the form of one’s Buddhist practice. If one took the texts out of the show and chanted them, that would be a complete practice in the Vajrayana tradition. Projections are what one visualizes while practicing. The performers represent Dakini, female energy, and at its ultimate nature it’s phenomena [or things that happen in the universe].

What is meditation, exactly?

Say that all your thoughts are a stack of papers and your emotions are the wind rustling your papers and blowing them everywhere. Your life is spent collecting everything and putting it in order – meditation is as simple as a paperweight.

The idea behind meditation is mind training. There are many layers and variations within consciousness and the mind. The process of meditation is familiarizing oneself with the mind and all those different levels. Becoming familiar with the way one’s mental processes work and thus becoming familiar with the root of suffering or what behaviors lead one towards suffering.

What does Buddhism offer Jews?

At a fundamental level, there is something missing. Even though we live like kings compared to the rest of the world, we are still not happy and satisfied. The mind is the source of suffering, and also the source of happiness. The teachings of the Buddha directly address this, and that is why I think many Jews, who come from a very intellectual culture, and yes, are very neurotic culture, respond to these types of teachings. Teachings on letting go of attachment, egolessness, the impermanence of all phenomena, limitless compassion, and all the rest -it’s all very useful. Just imagine if every Jew and every Arab made compassion their main practice, rather than clinging to a mental construct that labels ones cultural and genetic habitual patterns as a solid “identity”. This could lead us out of suffering permanently.

Animations by Peyton Harrison accompanied by composer Philippe Treuille’s original music score.

Look out for future performances.

*****

Additional reporting from Jayson Littman.

[…] [link] […]