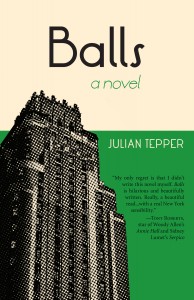

Comparing Julian Tepper’s debut novel Balls to a Woody Allen film risks missing the point. (For purposes of this post I’m referring to Allen’s meta, comi-poignant, New York-centric classics like Annie Hall, Hannah and Her Sisters, and Deconstructing Harry.) Tepper is Generation Y and his narrative voice reflects that: introspective where Allen would stop at ironic, lingering in places where the filmmaker would cut up and run. Nevertheless, Tepper, who played the waiter in Extremely Loud and Incredibly Close, channels Allen in the book’s trailer (posted below) down to the jazz; so briefly compare I will. But first the men: they both write, they’ve both appeared on the big screen, and you know how Allen loves his clarinet? Well, the Spoon hit “Don’t You Evah” was originally called “Don’t You Ever” and sung by The Natural History, Tepper’s former band.

Comparing Julian Tepper’s debut novel Balls to a Woody Allen film risks missing the point. (For purposes of this post I’m referring to Allen’s meta, comi-poignant, New York-centric classics like Annie Hall, Hannah and Her Sisters, and Deconstructing Harry.) Tepper is Generation Y and his narrative voice reflects that: introspective where Allen would stop at ironic, lingering in places where the filmmaker would cut up and run. Nevertheless, Tepper, who played the waiter in Extremely Loud and Incredibly Close, channels Allen in the book’s trailer (posted below) down to the jazz; so briefly compare I will. But first the men: they both write, they’ve both appeared on the big screen, and you know how Allen loves his clarinet? Well, the Spoon hit “Don’t You Evah” was originally called “Don’t You Ever” and sung by The Natural History, Tepper’s former band.

Balls centers on thirty-year-old Henry Schiller, an underachieving musician dying of testicular cancer while his younger, more gifted girlfriend rises to fame. He’s a neurotic Jew (the last of his family still in New York–is that not a theme Allen somehow overlooked all these years?) with a problem down there, an emasculating woman, a fear of telling loved one’s he’s ill…. The novel is an Allen-esque eye-roll at all things cojones (except cocktail parties), against a Manhattan backdrop that includes a sperm bank, under-lit piano lounges and the office of a shrink. Yes, the unhinged therapy trope possibly predates therapy itself, but Allen set the standard–and Tepper, in Heeb’s exclusive excerpt, lives up to it. Henry’s just learned that he’ll never have kids and is wondering if the recently-discovered lump in his groin is the product of an unexplained depression he experienced six years earlier. Enjoy.—Judith Basya

Henry at the Sperm Bank from Julian Tepper on Vimeo.

*******

Riding the subway one afternoon he ran into an old friend, Whitney Shields, the clarinetist. Whitney was twice Henry’s age. The nose on his tender face was long and narrow with a complex, ridged tip. His large brown eyes were full of knowledge. At the sight of him, Henry’s guard lowered and he told Whitney about his dizziness.

Brother, he said, to Henry, it sounds to me like you need help.

You’re probably right. It’s hard for me to admit, but I think I do.

You ever tried a shrink?

I haven’t.

I tell you, they’ve pulled me out of a few slumps.

Henry called Martz to ask for a referral. He suggested a psychiatrist, Penelope Andrews, on the West Side. Martz didn’t know her personally, but had heard good things. Henry contacted her at once. Just minutes into their conversation, in a soft, unhurried tone, she’d told him he sounded troubled. Henry had felt grossly misjudged. How could she know so much about him? Was she a psychiatrist or a psychic? He considered canceling his appointment. But desperate to feel better, he showed up at the scheduled time. Indeed, many of the doubts he’d had about coming were soon quashed by the doctor’s long, smooth, un-stockinged legs which crossed before him during their first session. She wore a short dress of a kind of powder blue color. Hers was a full bosom and she had the sort of fleshy stomach which made Henry want to grab on. Brown wavy hair hung past her shoulders. Greeting him at the door to her office on West 81st Street, her mouth, full and red, had smiled at Henry.

He’d said, Nice to meet you, doctor.

And she’d told him, Please, call me Penelope.

Before sitting Henry had looked around the room. Would he be open with his thoughts here? The brown wall to wall carpeting was oppressive. The drawn curtains sealed them into a semi-darkness, which affected him like a soporific. The dark wood shelves and thick medical volumes were stifling. He found a number of things to complain about. But sitting across from Dr. Andrews, his energy, his spirit, returned. Oh, she was something to look at. She was beautiful.

During the first half-hour Henry spoke about his condition, when it began, why he believed it had. He told her of his struggles with music. But he wanted her to talk. He knew his own thoughts, and was tired of them. However, not until the end of the session did she say much of anything. With Henry’s throat dry from speech, in the sleep-inducing light, Dr. Andrews, who had exceptional calves, gazed sideways at her patient and said to him:

Henry, you remind me of a man who came to see me about a month after 9/11. He was maybe ten years older than you. He’d worked in the north tower. Or was it the south? She touched her forefinger to her lips and said, I don’t remember. But the first things he complained of were symptoms just like those you’re describing: Dizziness. Filter. Exhaustion. Trouble working. Depression. I diagnosed him with Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder. He’d been through something which had shocked his whole system: Getting out of that building alive, losing friends, watching it all happen again and again on the television—he fell apart. But I’m left to wonder, Henry…were you here on 9/11?

Henry’s neck lengthened, his eyes shut. He wasn’t sure how any of this was relevant. But he was not the expert. Shifting forward in his chair, he said:

I was on my roof. I’d been living downtown.

Did you see the towers fall?

I did.

And how did you feel afterwards?

How did I feel? Like anyone else, said Henry, I suppose I was shocked, afraid.

She said, Right, then wrote something on her yellow pad. Tell me, did you experience any loss of appetite?

No.

Libido?

I can’t say.

Were you alone when it happened?

I was, doctor.

All alone?

There were others on my roof.

Friends?

Henry gave her a cross look. As much as any neighbor in New York is a friend. I guess we did talk to each other.

But otherwise you were alone?

I was.

A mournful expression on her face, she leaned forward in her chair and said, I’m sorry, Henry Schiller. I am so, so sorry. It must have been so hard to be by yourself that day.

Henry said nothing. He had no answer in mind.

The doctor was talking again. She was saying, The man I described for you, Henry, you should know, I fixed him. I made him better.

That’s what I want, doctor. I can’t tell you how bad this dizziness has been for me. I’ve never gone this long without playing piano. I can’t remember the last time I’ve had anything but a one-night stand. I’ve fallen out of contact with my friends. I’m lost.

The doctor frowned, in earnest. She said, Well, I want to help you, Henry.

Thank you, doctor.

I’m going to help you.

Good. Good.

You said you were on your roof, all alone…what happened next?

Henry left Dr. Andrews’ office that day in a state of extreme ambivalence. On the one hand, he didn’t see how meeting once a week for forty-five minutes to discuss the events of 9/11 would improve his equilibrium or restore the confidence he’d lost in his songwriting. On the other, the doctor smelled so good, some perfume she wore, a faint orange aroma that turned him on in a way no woman had for years, and when deciding whether or not to see her again he couldn’t help but imagine her heavy bosom and smooth knees—he became erect. They were scheduled to meet the following Thursday afternoon. Henry showed ten minutes early. Dr. Andrews began the session by explaining how her methods of treating 9/11 victims were somewhat untraditional. But Henry, mesmerized by the sultry tone of her voice, didn’t hear her description. Nor did he ask her to repeat herself. They spent the time watching cable news, the doctor studying Henry’s reactions to any mention of Iraq and Afghanistan. The next week they went to visit the World Trade Center site. Henry followed the doctor’s instructions, staring long and hard at the building’s footprint and like the Surrealists speaking aloud those words, any words, which came to mind:

Landscape. Cabbage. Breast. Future. Muffled. Face. Disturb. Exist. Eyeballs. Blisters. Partner. Gray. Despair. Entombed. Influx. Clasp. You. Lidless. Lizards.

That’s good, Henry. That’s very good.

Really?

Oh sure, Henry. You’re doing splendidly.

He valued her encouragement. But then these days, whether staring at CNN or the WTC, Dr. Andrews didn’t mind when he touched her arm or placed his hand on the small of her back. She didn’t protest when he hugged her goodbye, pulling her tight against his body. She said nothing when he complimented her beauty. At times he thought he’d pay even more for her services.

That opportunity did soon arise.

The doctor said she was dissatisfied with their progress. Henry was still dizzy, depressed and closed-off musically. She proposed he start coming twice-a-week. Knowing her rates were high for him, she offered him a special price: two sessions, $300.

Take a minute, Henry. Think it over.

But Henry, breathing in that profoundly erotic mandarin aroma, told her he didn’t need time. Yes, was his answer.

Yes.

He started seeing the doctor Tuesday and Thursday afternoons. Though finding no improvement in his symptoms, his fantasies about Andrews were becoming more regular. At night he closed his eyes, imagining her naked breasts, her ass. In the morning, they occupied his mind again. Enveloped by thoughts of her legs, he missed his stop on the subway. On the street he saw women with similar hair and build and followed them for blocks, thinking they might be her. He couldn’t recall the last time a woman had taken possession of him like this. Perhaps he should stop seeing the doctor. Could this be healthy? He knew it wasn’t. But he couldn’t bring himself to tell Andrews it was over. He looked forward to their time together more than anything else during the week. He wouldn’t give it up. He considered discussing these feelings with her. Why not? She’d told him many times that he could tell her anything.

In fact, one day Dr. Andrews, seated with her silken legs crossed and her hands folded under her chin, raised the subject herself.

Henry, she began, there’s something I’ve been meaning to discuss with you.

The pulse at the sides of his head increased. He could hear its heavy thumping in his ear. He didn’t move.

Andrews, glancing from him to the floor, drew her fingers up her long, supple neck. She said to him, I’ve had patients fall in love with me before, and, as difficult as that can be, I don’t think it has to mean the end of our work together. We have to talk about it, though. We have to figure out what’s happened.

Andrews placed her notepad under the chair, as if to tell Henry that this was not a patient-doctor matter.

Is that really what you think, said Henry, that I’m in love with you?

Dr. Andrews, bringing her hands over her lovely round knees, said, It’s clear to me that this is precisely the case. You have nothing to feel ashamed of, Henry. You’re a young man. You come here twice a week to unburden yourself to me, a woman some ten years your senior, and have the chance to speak your mind in ways you can’t with any other person. Dependencies do develop. It’s no surprise that you’d try and keep me close through sexual relations. Henry, she said, flashing her smile, I’ve sat with you for months. I know what’s going on.

It’s true you’re such a beautiful woman, Penelope.

Mmm-hmm, she nodded her head. You’ve said so before.

I’ve thought about you intimately since the moment I met you.

I know you have, Henry.

Until now, Andrews had maintained a serene look on her face. But folding her arms under her chest and staring at Henry with commanding eyes, her expression became serious. She explained how she’d never once had intercourse (that was her word) with a patient and that she wouldn’t begin now. She said her practice was her life, it meant everything to her. If only Henry knew how hard she’d worked to get here, she could never jeopardize her place in the field of psychiatry, not for anything. Her mind told her it couldn’t happen. Her mind said no.

Leave a Reply