By Brian Heater

“What is art to you?” I’m silent for a moment. Not because I’m thinking hard about the question—at least not at first—but rather, because my first inclination upon being asked is an attempt to deduce whether or not Art Spiegelman is fucking with me. It’s a fair question, I suppose, and one that has painted much of Spiegelman’s life and work. The artist’s name is perched high atop a short list credited with knocking down the intellectual wall dividing comics from art, an act oft attributed to the 1991 publication of Maus: A Survivor’s Tale. The Pulitzer Prize-winning comic book memoir of the time Spiegelman’s father’s spent in Auschwitz helped popularize both the term “graphic novel” and the medium, within the academic world and without.

Spiegelman, however, is not smiling at his own question. He’s clutching a Camel in one hand and resting the other on the table, next to a glass full of lime-flavored Diet Coke, awaiting an answer to a question that, after a moment of silence, it becomes clear was not intended to be purely rhetorical. “Sorry to be so professorial, but when we talk about ‘high art’ and ‘low art,” we’ve got to start with that stupid college question: ‘what’s art?'”

It’s easy to forgive Spiegelman his trespasses into the academic, after the years he spent teaching comics history at Manhattan’s School for the Visual Arts, and at my own alma mater, UC Santa Cruz. (In the far Left-leaning beach town the artist’s insistence on being allowed to smoke during a lecture inspired a local paper to winkingly announce “He’s Gonna Smoke ‘Em if He’s Got ‘Em.” Spiegelman, for his part, has used any number of platforms, his own comics included, to decry the erosion of smokers’ rights).

Suddenly put on the spot, I prattle off a few contradictory answers: something about creative pursuit and something about craft. It’s clear that neither is especially satisfactory to the artist, whose work, both consciously and un-, has so often tested and defied the artificial boundaries of this utterly simplistic, if wholly important question. “In college, this sucked,” says Spiegelman, taking a drag. “I spent an entire semester where basically all my grad student teacher could come up with for us, after trying to Socratically teach for a session, was that ‘art is anything anyone claims is art,’ and that’s almost useless.”

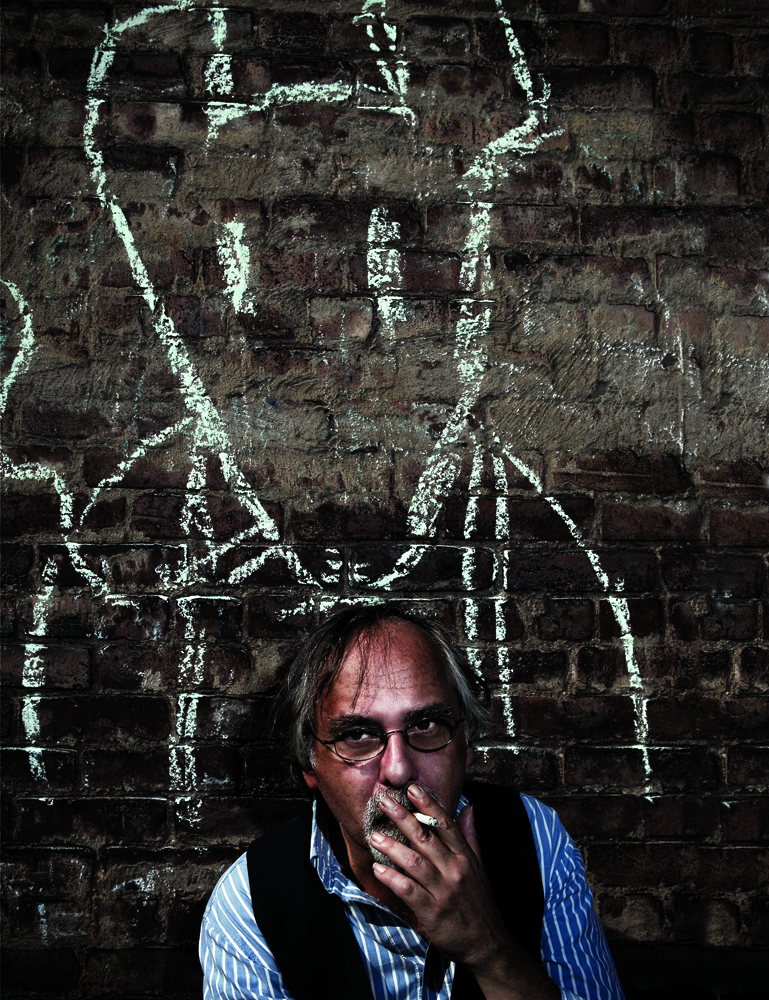

photo (c) seth kushner

Useless, perhaps, but is it entirely inaccurate? “Yeah,” Spiegelman issues a monosyllabic answer to a question that’s clearly given him some amount of trouble, over the years. “That’s where it stayed, until I was going to the dentist with my daughter, a few years back,” he adds. “Just as I’m about to take my turn in the chair, she says, ‘Papa, what’s art?’ Since I won’t even get my teeth cleaned without laughing gas, I spent the next hour with nitrous oxide clamped to my nose, trying to figure out what art is. On the way out, I said, ‘art is anything that gives form to one’s thoughts or feelings.’ And I think that’s a better definition than the one I got in college.”

For Spiegelman, the publication of Maus was perhaps something of a personal vindication in a career-long battle with the perceived comic/art binary. It was a struggle that peppered much of the artist’s work, decades before the publication of Maus‘s first volume, when he was toiling away on the left coast amongst underground comics peers like Robert Crumb, S. Clay Wilson and Gilbert Shelton. These artists, who reached their full potential some time before Spiegelman, continue to elicit in him a rare humility in the one aspect of his work where he still feels a tangible sense of insecurity: his own artistic aptitude.

“I was certainly running to keep up with my betters and elders, but at a certain point, something really possessed me,” Spiegelman explains. “There was a point where it was hard for me to articulate what was important to me about that work and what allowed it to be important elsewhere. I think I was part of this swell taboo-busting gang of artists, but there was this one taboo that I needed to walk to the edge of and over. It made me move outside, onto new terrain’ a wonderful realm of psychedelic wooliness. That was the taboo of a cartoonist calling himself an artist.”

If Spiegelman’s work hasn’t made clear his thoughts on the subject, the framed comics pages that line the entranceway to his SoHo studio certainly put the question to rest. The space, a fifth floor walkup a few miles from the apartment he shares with his wife, New Yorker art director, Francoise Mouly, played a significant role in the artist’s 2004 9/11 graphic meditation. In the Shadow of No Towers was Spiegelman’s first major work since the publication of Maus, a dozen years prior. The space is roughly twice the size of my humble Queens apartment, a one-man tribute to the art of the comic book, with a Mac perched at its far end, serving as the artist’s workspace. Upon entering, Spiegelman smilingly refers the space as “The House that Maus Built.”

And, if any lingering doubts remain as far as Spiegelman’s reliance on the visual to effectively convey his message, the artist frequently pulls books down from his many shelves to illustrate his various points. By the end of the hour-long conversation, there are a half-dozen sitting between our two glasses of lime-flavored Diet Coke, all by Spiegelman. The first, and arguably most central to the vast majority of topics that arise over the course of the interview, is a freshly printed copy of Spiegelman’s new retrospective, Breakdowns: Portrait of the Artist as a Young %@&*!

Described perhaps most accurately as the comic equivalent of the Criterion Collection, the middle third of the book is a fairly standard reissue of 1978’s Breakdowns, a collection of work created by the artist earlier that decade for assorted publications. That book was, “published against all odds,” Spiegelman writes in an essay that comprises the last third of the book. “There was no demand for a deluxe large-format album that collected the scattered handful of short autobiographical and “experimental” pieces made between 1972 and 1978—except by me.”

Three decades later, the book’s significance is clear (helped in no small part by the aforementioned afterword and a long-form sequential art introduction), both as a window into the early work of an artist who would prove one of the medium’s most celebrated and as a document of the seed for some of future generations of artists’ most important work. The book makes several key blind leaps into the wilderness that Spiegelman is not modest about celebrating. “I’m gonna sound like a nut,” he apologizes, briefly, “but there wasn’t a Watchmen before there was an Ace Hole, Midget Detective, and there wasn’t the heady intellectual stuff from Chris Ware. They’ve acknowledged their debt to one specific strip or another. They all do great work that I admire, but it’s something to find a way to make an utterance for the first time, which is what leaves me proud of the work done in here. It’s really hard to say, because you’re never supposed to say that about your own stuff. Someone else is supposed to do it.”

The book’s true centerpiece is a humble three-page work, which gave the original edition of the book its retroactively confusing subtitle, “From Maus to Now.” The art in this short-yet-potent strip bears the clear influence of Spiegelman’s best-known contemporary, Crumb, one of those “betters” to whom the artist spent his early years attempting to catch up. Originally published in an anthology carrying the—at least partially—ironic title, Funny Animal Comics (which, much to the excitement and nervousness of an eager young Spiegelman, boasted a cover by the already legendary Fritz the Cat artist), the story bears only a passing resemblance to its successor of the same name, planting the seeds of Spiegelman’s career as an autobiographer and casting the graphic interpretation of his father’s memoir of Auschwitz with the stock cartoon binary of cats and mice.

The piece, short and raw as it is—along with its adjacent tale, Prisoner on the Hell Planet, the tale of his mother’s suicide which would resurface in its original form in the graphic novel version of Maus—brings us to Spiegelman’s secondary definition of art. “It’s also finding a way to communicate the business and horror of being alive to someone else,” Spiegelman explains. “That’s a heady endeavor, and at the time, I believed in it thoroughly. Back in that 1970s work, this was the work of an atheist trying desperately to find something to believe in and deciding, maybe it’s art.”

The endeavor he speaks of is, at the very least, a background player in much of Spiegelman’s early work and the coalescence of Maus as the medium’s major achievement. Its presence is unavoidable in Spiegelman’s subsequent major work, No Towers, which finds him cowering, for much of the book, in the shadow of the 9/11 attacks on the World Trade Center, a mile and a half from the womb-like cartoon warmth of his studio.

“Somewhere along the line I said, and I think it’s come back to haunt me,” begins the artist, ‘terror’s my muse.’ I think it’s in the No Towers book. It was certainly true for those two pieces of work. Breakdowns is dealing with something else, although it certainly deals with personal horror. It’s not catalyzed by terror. On the other hand, I don’t work when I’m happy. I’m usually marshaled at gunpoint to the drawing table and told to not get up until I’ve come up with something. So, that much is true, but on the other hand, there’s very little happy art that I take great stock in.”

To some degree, terror even plays a minor role in Spiegelman’s other new book that came out a few weeks after Breakdowns. Published by Mouly’s new young children’s imprint, Toon Books, Jack and Box is, at least on its surface, a stark contrast to Breakdowns, juxtaposing and highlighting another primary driving force in much of Spiegelman’s post-Maus output: the desire for constant reinvention. After [Maus‘s two volumes were] finished,” Spiegelman begins, “all the world wanted from me was a fucking Maus movie or Maus Three. I had to tell people that the war ended and my father died, and that’s that. On the other hand, I didn’t feel that my next move should be anywhere on that terrain. First of all, I certainly didn’t want to be the Elie Wiesel of comic books. And I like to be a moving target. I think you’d be hard pressed—though I can explain it perfectly—to find out what Jack and the Box and Breakdowns have in common. They don’t look the same, they feel rather different, and I’m maybe one step too close to it to know if you could, without my name on it, recognize that they were both from me.”

On a base level, Jack and the Box, a book for beginning readers, based on a post-kindergarten reading list, is also catalyzed by terror. Arguably the grandchild of Breakdowns, the book tells the story of a young rabbit who grows to love his new jack-in the-box, an appreciation that can only occur once he’s overcome the toy’s initial terror. It’s strange, it’s Freudian, and ultimately, it’s adorable as hell. But even with its obligatory happy ending, the book in some sense gives form to the aforementioned horrors of being alive. And as always, it begs that ever-important question: is it art?

Read Brian Heater’s extended Q & A with Art Spiegelman at TheDailyCrosshatch.

i think art is what you make it, but then again, don’t trust me. I’m a horse’s ass.

Brian Heater is the man! Please more Brian Heater in Heeb!

Agreed, and more comix coverage!

I’m so over A.S.