[This interview originally ran in Feb. 2004, as part of HEEB‘s 6th print issue: “Guilt“]

Cornel West is nearly as at home in the New York Jewish intellectual scene as he is in the black community. He has spoken in countless synagogues, Hillels and JCCs, is the co-chair, with Michael Lerner and Susannah Heschel, of the Tikkun Community, and is a frequent writer on black-Jewish relations.

Yet for all West’s engagement with the people of the book, members of the tribe have been among his most vociferous critics. Several Jewish pundits have derided West’s credentials, calling his success in the Ivy League a monstrous mistake brought upon by affirmative action, white guilt and the academy’s leftist bent. Author David Horowitz called him “an incredible intellectual lightweight” and a “racial demagogue.” Neocons Hilton Kramer and Irving Kristol boycotted a conference at which West was to deliver the keynote address, claiming he was “not enough of scholar.” And the critics are not limited to right-wingers; writing in The New Republic in 1995, liberal Leon Wieseltier dismissed West’s entire corpus as “worthless.” West’s work, he wrote, was “noisy, tedious, slippery, sectarian, humorless, pedantic and self-endeared.”

These attacks, and unease with West in many Jewish circles, stem from several incidents. In the ’90s, West challenged Louis Farrakhan to become more proactive, inspiring the idea for the Million Man March. West had condemned Farrakhan’s homophobia and anti-Semitism, but many Jews still felt that any contact with the controversial minister only helped legitimate a bigot who should be marginalized. Years later, West was arrested with Lerner while protesting Israel’s escalation of its war with the Palestinians. This, paired with West’s public camaraderie with the late pro-Palestinian scholar Edward Said, raised Jewish eyebrows.

The climax came in the wake of a famous dispute with Harvard president Lawrence Summers in 2001 and 2002. Summers had accused West of not being a responsible academic, claiming West skipped classes and had not produced a serious scholarly work in many years. During that time, West had released a hip-hop album, teamed up with the Wachowski brothers to guest star as a wise counselor of Zion in The Matrix sequels, stumped for Bill Bradley, Ralph Nader and Paul Wellstone, and signed on to Al Sharpton’s presidential campaign.

Deeply offended, West announced that he was thinking about leaving Harvard for his old post at Princeton. Summers’ public apology, a petition by Harvard faculty asking West to stay and West’s 2002 departure for Princeton’s Religion Department all prompted critics in Commentary and elsewhere to weigh in, often harshly, on Summers’ side.

West would later quip on NPR’s Tavis Smiley Show that the Jewish Harvard president was the “Ariel Sharon of higher education,” a comment that set off accusations of anti-Semitism. To many Jews, West now looked like yet another black demagogue, one tenured in the heart of the Ivy League.

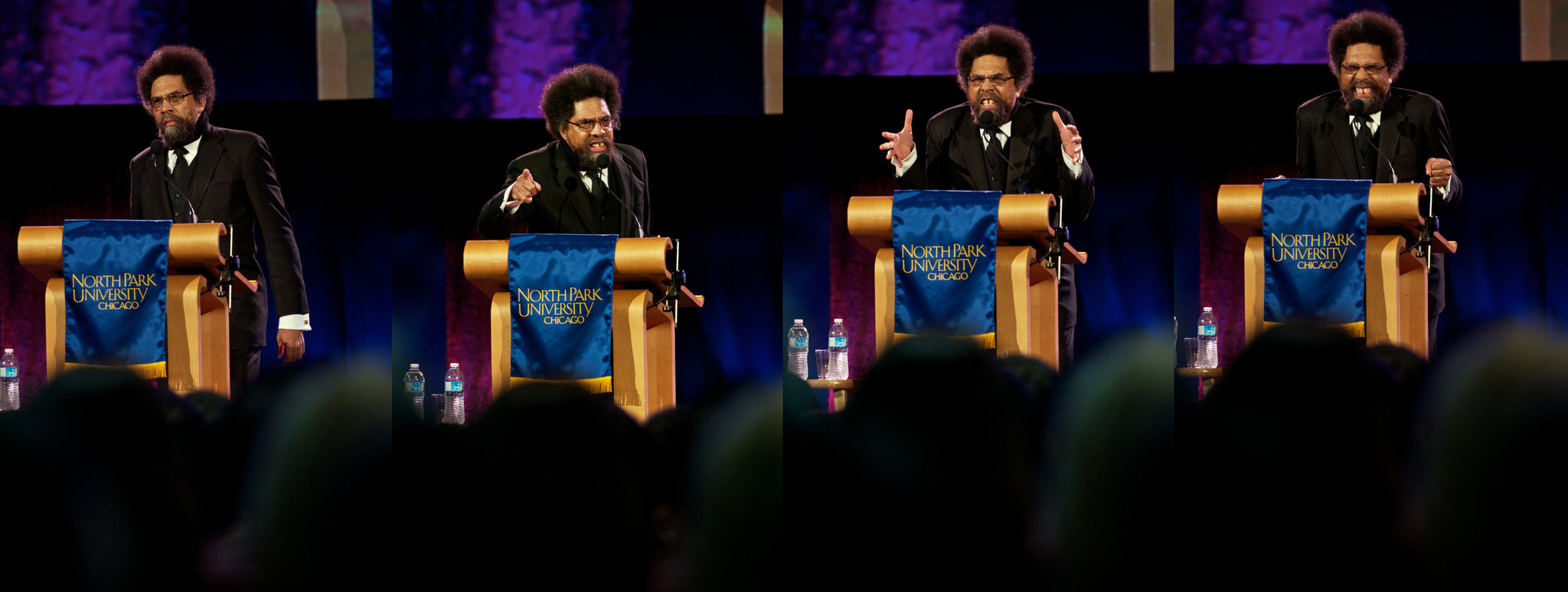

At Princeton, West enjoys a cult-like following. A parade of hangers-on dogs his lanky steps around campus, and his marathon office hours draw crowds of students lined up outside his door. His courses fill the largest classroom on campus. His complex lectures on literature, politics and philosophy are delivered without notes, like sermons. Earnestly interested in who people are and what they are doing, West takes time to talk respectfully to every comer—well-wishers, critics and comrades alike. He holds court at the local greasy spoon, The Annex, entertaining his big tent of interlocutors with stories and insights about jazz, Colin Powell and the meaning of the Tragic. West spoke to Heeb in his small office at Princeton.

Heeb: After you published Blacks and Jews: Let the Healing Begin you went on tour with Michael Lerner, speaking to black and Jewish audiences. You were well-received by Jewish agencies in Boston and elsewhere.

West: That’s right, that’s right.

Do you feel that the Summers incident and your activism against the Israeli occupation soured your relationship with the Jewish community?

I don’t think so. I think that there is a very real divide in the American Jewish world in terms of [those who are] pro-Sharon and those critical of Sharon. The crowd that has been critical of Sharon is very embracing. Their support is crucial, and I appreciate that.

Many Jews were suspicious of your cordial relationship with Farrakhan and speaking at the Million Man March.

Yah, Brother [Michael] Walzer hit me—said the Nation of Islam were like fascists in Italy! I said, “Well, that’s stretching it brother, that’s stretching it!” But he was upset, I can understand that. So many Jewish progressives, like my dear sister Letty Cottin Pogrebin, were deeply critical of the march. I am thoroughly convinced I did the right thing, and of course it’s clear that my brother Minister Louis Farrakhan has shifted in significant ways away from his earlier anti-Semitic remarks and noises.

He doesn’t seem to be much on the radar screen lately, but he has been the subject of countless fundraising letters I receive in the mail meant to scare grandma into donating money for the fight against anti-Semitism.

Well, he speaks every week. He was very critical of the Iraq invasion, of Bush’s foreign policy, and has been talking about the Israel-Palestinian conflict. But he’s been able to swerve, for the most part, from any anti-Semitic remarks. And I celebrate that, because all principled criticisms are welcome, and his as much as anyone else’s.

Some Jews labeled you anti-Israel or even an anti-Semite after you compared Summers to Sharon.

I think that the complex dynamics of the American Jewish community are undergoing some fascinating transformations. I think there are more voices putting forward an indigenous critique. A slow glacial shift is taking place in American Jewry that is much more open to the best of the Jewish past, which is one of serious self-criticism, self-questioning and self-interrogation. This shift is creating new discursive possibilities, not just around Israel. This is true for a number of different issues, but most manifest around Ariel Sharon’s myopic leadership more than anything else. People that really care about Jewish suffering, who are really deeply concerned about Jewish survival, recognize that they have to explore alternatives that 10 years ago were viewed as completely off the map.

How do you think the Jewish community, or its left wing, can regain its moral center, especially on domestic, urban and race issues?

It’s important to keep in mind that even before the Kishinev pogrom in 1903, Abraham Cahan’s Jewish Forward called lynching in the South a “pogrom in America.” Up through the 1960s, the Jewish community was the most progressive community outside of the black community concerned about black suffering. That legacy has never died. Even among American liberals, many of whom are conservative on Israel, many still remain tied to the struggle against racial injustice. There is a kind of asymmetry between the

domestic concerns of the vast number of American Jews, very liberal and progressive, and the Middle East. When I look at the Anti-Defamation League, for example, they have done some very important things in terms of keeping a focus on black suffering, no doubt about that. I agree strongly with brother Foxman when it comes to his pronouncements about increasing anti-Semitism, but when the ADL can give an award to an Italian prime minister who might have anti-Semitic elements, and celebrate him because he’s supposedly pro-Israel in their way, well there I’m very critical of Foxman. But when we look at particular programs and when I meet people in the organization, they’re doing a number of wonderful things as it relates to the injustice done to black people.

When I was in Boston, wonderful sister Nancy Kaufman worked with Rev. Eugene Rivers on community policing. My late brother Leonard Zakim headed a black-Jewish alliance. Did magnificent things in Dorchester and Roxbury as a member of the ADL. We worked closely together, even though he and I clashed when it came to the Middle East. For me it’s a matter of gaining the moral consistency to focus on what they’re doing domestically but being self-critical so they can make the same sort of moral and political pronouncements when it comes to the suffering of the Palestinian people. Also, it’s important to keep in mind the Israeli working class and poor are being pushed against the wall by the right-wing economic policies of Sharon and Netanyahu. I’m deeply concerned about the suffering of the victims of barbaric suicide bombings and the victims’ families. But I’m also concerned with the Israeli working class and the Israeli poor, who are often rendered invisible. There are major strikes going on right now! That class struggle is intensifying. Why? Because underneath the colonial policy is this increasing austerity program where vulnerable Israeli citizens, be they Jewish or non-Jewish, are suffering.

And of course public resources have gone to the settlements instead of the Mizrachi working class and the development towns.

Exactly, very true.

In Race Matters you have a chapter called “Nihilism in Black America.” Could we say there is a sort of Jewish nihilism? What would it consist of?

Hmmm …Well, I think that there are two distinctive features of the American Jewish community: the high level of civic activism, unbelievable levels of organization—this is to be applauded. This is what democracies are all about. Second would be the high levels of education. Among young Jewish brothers and sisters there is a profound hunger and thirst for something more than either material toys or the kind of blind deference to Israeli policy. The first has to do with their sense of feeling that life has meaning and significance simply beyond the materialist quest that has been so characteristic of any middle class in the last 40 years. The second has to do with Jewish identity, there has to be more to it than a defense of Israel regardless of what the policies are. This is no longer holding among this young generation of Jews. In that sense you have two positive elements. You got this hunger beyond materialism, hedonism and narcissism and a hunger for a richer, deeper understanding of Jewish identity, which is linked to their human identity. We’re at a transitional moment. In my next book, Democracy Matters, I have a whole chapter on Diaspora Jewish identity in America.

You’re not a Zionist, but unlike your good friend Edward Said, you seem sympathetic to those who are advocates of the Jewish national project. You’re hard on Sharon and Arafat, but unlike many on the left, you speak about Israel itself without bitterness. I’m sure there are those on the left who say you are not left enough. How do you strike that balance?

In terms of present-day Israel, for me it’s really a question of viewing Israel as any other nation-state. It is a precious, fragile, democratic experiment that has some wonderful and virtuous aspects in terms of breakthroughs against immeasurable levels of adversity in its forming and founding. But at the same time we have to keep track of its non- or anti-democratic or downright colonial elements as well.

Now the late, great Said and Chomsky mean very much to me. Chomsky, I think, is the most courageous political intellectual of our time. I don’t always agree with him—his Cartesian rationalism deeply irritates me! No doubt both he and Said would be critical of me for not being more radical in my critique of the American Jewish establishment, but that would cut off dialogue with the vast majority of American Jews, the vast majority who are liberal and progressive. I try to strategically be in dialogue with a number of Jewish voices that Chomsky and Said had very little access to. Now, if I reach the point that in telling my truth I’m cut off, then I have no choice. By working with my dear brother Rabbi Lerner and sister Susannah Heschel I at least have a foothold in the dialogue, so I feel like I can be a much better force for good being part of the discussion rather than an isolated voice on the outside.

Who else carries the torch for the Jewish progressive intellectual tradition?

I think the most important secular Jewish voice right now is Tony Kushner. He represents for me such a high level of intellectual candor, courage and moral sensitivity—and he’s a great artist. When I heard his speech last year at the Tikkun Campus Network conference, I had not heard a more powerful and fresher voice. He represented to me the best of prophetic Judaism, the best of internationalism, the struggle for freedom and democracy. My own religious sensibility would be different when it comes to debates about religious traditions. But he struck me as the freshest I’ve heard in a long time.

Lionel Trilling, the first Jew to teach in Columbia’s English Department, was the mentor of Leon Wieseltier, who has written such withering things about your work. You’ve written about Trilling and use some of his ideas. Do you think Wieseltier’s nastiness is fueled in part by a sort of possessiveness of this legacy?

I think Leon Wieseltier’s problem is that he was supposed to be the boy wonder. When you are trained under [Isaiah] Berlin and Trilling you’re not supposed to end up the literary editor of an ideological rag. You’re supposed to be a major intellectual presence. No doubt he’s very smart, but at the same time his arrogance and lack of discipline and his unwillingness to engage in sustained high-quality intellectual dialogue results in this journalistic presence rather than a serious intellectual presence. I think he resents that. I can understand that. I can actually sympathize with him. The mantle of Berlin and Trilling was one of internationalism and universalism, whereas Leon is a tribalist, pure and simple. He makes it very clear: “This is Our people,” “This is Our interest,” “This is Our security”—this is tribalism! The kind of thing his teachers would be not just critical of, but would be embarrassed by it. Well, you could argue that their internationalism isn’t appropriate anymore. But the great Jewish intellectuals at the end of the Second World War—Auerbach, Hannah Arendt, Berlin—they went back to the great humanist tradition, culled it for what it can provide. They supported the State of Israel as internationalists, but only to the degree that it aspired to democratic aims and ends. It’s easy to describe me as a black tribalist, because it mirrors their own tribalism. But I’m not. I’m not a nationalist—I may work with certain nationalists, but I’m an internationalist.

You’re supporting Al Sharpton’s campaign for president, even though most leftists don’t think of him as their candidate. Why do you consider his candidacy important?

If you’ve seen the debates you can see he is one of the best voices there, not just as a wise cracker, but raising certain issues, being courageous in the face of the sheer hypocrisy and milquetoast character and spinelessness of so many Democratic candidates. You need to have someone doing that. I like both Dennis [Kucinich] and Sharpton. They’re the progressive pole, focusing on issues of the criminal justice system, mandatory sentencing and soft drugs, prison-industrial complex, welfare reform, wealth inequality, ecological abuse. Whoever accents these issues I’m going to be with—in the primary. Al Sharpton, in raising those issues, ensures that the Democratic Party doesn’t get off scot-free.

In the Matrix sequels, you play a councilman of Zion …

Counselor West!

This makes you an “Elder of Zion”!

(Laughs) I may be an elder of Zion, but the third movie makes a fundamental move from Schopenhauer to William James. Neo holds on to the will-to-believe … but it’s thoroughly humanistic! Thoroughly humanistic! Larry Wachowski is now a thoroughgoing secular Jamesian—now he believes in the centrality of desire. No longer Schoperhauerian, Buddhist-like, where you eliminate desire in order to engage in some contemplative activity that renders you distant from your humanity—to be human is to desire, there is no way around it, no way of escaping it. The question then becomes how does that desire appear in such a way that you can you still believe in something like hope without in any way having a religious or foundationalist grounding. And the third Matrix, that’s what it’s about. Messianic figures and salvific narratives: rejected! We only have each other.

You talk about “Athens” and “Jerusalem” as watershed spiritual moments. What is the place of “Jerusalem” in your worldview?

At Harvard, I majored in Near Eastern Languages and Literature, wrote my senior thesis on the concept of “revelation” in the Hebrew Scriptures. And of course “Jerusalem” was crucial to my fundamental intellectual formation in my own religious training coming out of the black Baptist church. In my own thinking, the legacy of Jerusalem sits in the center of who I am. The Hebrew Scriptures is shot through with a democratic dimension: the distinctiveness and uniqueness of each human being; the indestructibility of individuality; the dignity of ordinary, everyday people.

And how does Christianity fit into this context?

The Christian movement is unintelligible without understanding that it comes out of a prophetic tradition of Judaism, and I take quite seriously the Jewishness of Jesus, Paul, the early Disciples. The radical difference is that a particular Jew named Jesus of Nazareth does attempt to project a wholesale internationalism and universalism separate from any particular people or any particular community. The people that Jesus associated with, and that he projects in his Kingdom, has little do with any particular lineage, but has to do with outright choice, radical choice to be part of this kingdom of love and justice. I think the differences need to be preserved—it is important not to paper over or sugarcoat them. The basic sensibility of Judaism—with which I resonate—is that it is more radically this-worldly, more tied to the historical terrain. What Jesus introduced was an otherworldly eschatological dimension.

Most of your engagement with Jewish thinkers has been with the modern, mostly secular variety.

I see the 20th-century Jewish thinkers as fundamentally committed to modern notions of freedom and exploring it in all of its various modalities and possibilities. For me Kafka is so fundamentally committed to a conception of freedom that allows him to engage in deep forms of introspection, internal investigation tied to intellectual candor and honesty that we associate with the best of Renaissance humanism and certainly the best of the Enlightenment. And so I think that anytime we talk about modern Jews—I think that’s true of Marx himself—that they’re actually building on legacies of Jerusalem that are premodern. But what sits at the center of who they are, are these very modern notions of intellectual honesty, intellectual humility, intellectual freedom, fearless speech—parresia—from the Greeks. I love that about them.

image via (cc) flickr

You’ve described yourself as a Chekhovian Christian. You’re working on a project on Chekhov and John Coltrane.

That’s right.

Is there a relationship between Chekhov and Jewish literature?

You know, a great Jewish writer, Isaac Rosenfeld, argued that Chekhov had really written in Yiddish because the sensibility was so similar.

Of course, in Chekhov’s plays, everyone is interrupting each other. There we see some similarities!

But the blues-like characters of these Yiddish writers, unbelievable! They loved Chekhov. To. The. CORE! I think that the most Chekhovian literature ever written comes out of that brother right there I.B. Singer. He had a whole group of followers, and Sholom Aleichem. He’s another Chekhovian. It’s the blues on the page, it really is! The. Blues. On. The. Page!

What’s the commonality?

Yiddish writers, at their best, look darkness in the face and laugh! Chekhov would have loved the fact that the Yiddish writers took him up in the way that they did. You know he was the only great Russian writer to come out against anti-Semitism. All the other Russian writers were anti-Semitic to the core! See that genius right there, Dostoevsky, ugh! His talk about Jewish folk … Tolstoy died in 1910—“What do you think about Alfred Dreyfus?” “Got what he deserved!” Oh please, Leo! Shut up and go back to writing your great short stories! Now Chekhov broke with his benefactor, Souvorin, over his anti-Semitism! He thought Chekhov had lost his mind! Didn’t have any money, but he took a stand on this. It was very difficult. Would be like a white person in American standing up against white supremacy. Whole family going against you. Like bringing “Jamal” home. You know, mom says, “We said ‘love everybody’ but why you bringing Jamal home?” Chekhov’s first girlfriend was a Jewish sister. His first play, Ivanov, about this Jewish girl, his first love. To be in love with a Jewish sister does make a difference.

I should mention brother Arthur Miller, we go and see him every summer. [Points to a picture of himself in a blue shirt sitting next to Arthur Miller] First time in 20 years I didn’t wear a suit! In a way, Kushner is building on Miller’s justice-centered Jewish secularism. He’s got the courage along the way that is beyond description. I asked Toni Morrison, of all the writers alive, who do you respect and like the most, and she said, without skipping a beat, “Arthur Miller.” She only met him once, and for Toni to say something like that, a black genius 72 years old has met all kind of white folks in the world, she chose Arthur. Told this to him, he had tears in his eyes! He says, “I didn’t get a chance to know her that well; we only talked for a few hours!” She said that there’s something about his spirit that is un-be-lieve-able!

We could say the same about you, Brother West.

Leave a Reply