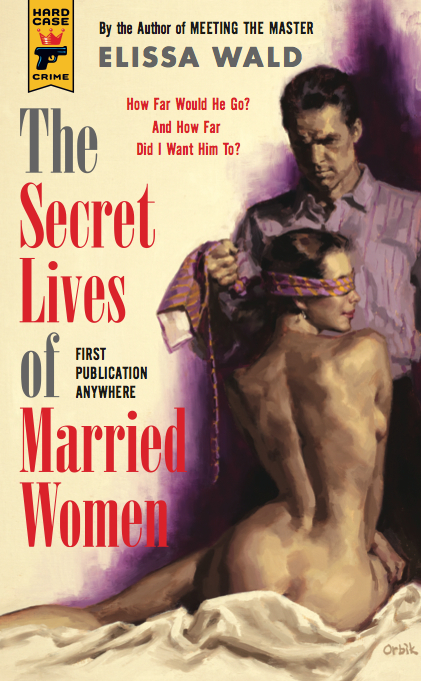

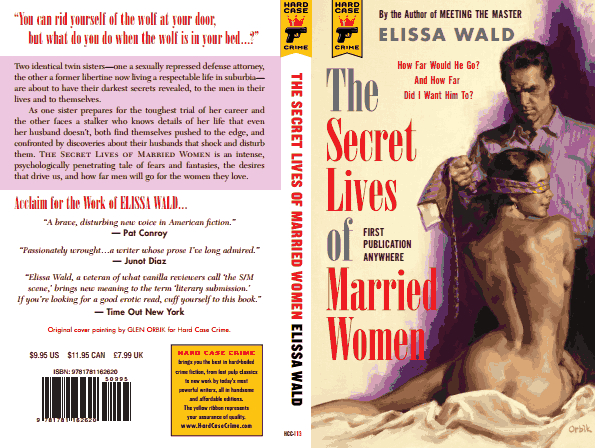

There’s one explicit sex scene in The Secret Lives of Married Women (though to be fair, it’s worth at least ten), one toe-fetish scene, and one visit to a bdsm dungeon that minus a couple of phrases would be rated G. That’s not a lot, quantitatively, for a book whose noirish cover depicts a man blindfolding a naked woman with his tie. Yet anybody familiar with author Elissa Wald’s previous work, 1995’s Meeting the Master and 2001’s Holding Fire, knows that she’s much more interested in what draws us to whips and chains (us–you didn’t land on this page by accident) than in the particulars of how we employ them.

There’s one explicit sex scene in The Secret Lives of Married Women (though to be fair, it’s worth at least ten), one toe-fetish scene, and one visit to a bdsm dungeon that minus a couple of phrases would be rated G. That’s not a lot, quantitatively, for a book whose noirish cover depicts a man blindfolding a naked woman with his tie. Yet anybody familiar with author Elissa Wald’s previous work, 1995’s Meeting the Master and 2001’s Holding Fire, knows that she’s much more interested in what draws us to whips and chains (us–you didn’t land on this page by accident) than in the particulars of how we employ them.

Secret Lives is a pair of novellas about twin sisters, opposites on the surface, digging down to their deeper erotic selves–women with healthy fantasy lives should easily relate. Equally intriguing in these tales, though, are the little twists of everyday menace that point the characters to their yearnings. I chatted with Wald about desire, submission, domination, stripping, tasers, French-maid slaves, and why it might be that I’m asking you nicely to read this instead of ordering you to kneel and recite each word.

**********

So, let’s start with the obvious question and get it out of the way. How does The Secret Lives of Married Women differ from Fifty Shades of Grey?

Well, the dynamics of domination and submission have been a lifelong preoccupation of mine, and they surface in nearly everything I write, and Secret Lives is no exception. But Secret Lives is very different from Fifty Shades of Grey. The female protagonist in Fifty Shades–Anastasia–is a virgin. Despite her beauty, her apparent capacity for passion, and her lack of any religious or moral objection to premarital sex, she has somehow gotten through college without a single sexual encounter. She is wooed by a kinky billionaire and drawn into an s/m relationship with him even though she herself has no particular desire to explore or inhabit that realm.

My women are very different from Anastasia. They aren’t supposed to represent some ideal of innocence or purity. They are adults with agency, they take ownership of their desires and they are active in seeking out their own gratification.

You’re known for humanizing s/m in that way, for making it about fully-developed characters rather than stereotypes with whips and chains. Yet you predominantly write from the point of view of the submissive–is that the more compelling angle?

Well, the most straightforward answer is probably that I identify primarily as a submissive myself, and so writing about submission is not only easier, but more personally compelling to me. It allows me to bring my own fantasies to life on the page, so the writing process is naturally more engaging and gratifying than trying to write about something that doesn’t deeply thrill me.

I’m glad you said “thrill.” The thrills you write about are not strictly sexual, at least not in the obvious ways. Everything is sexual, of course—you can take a photo of somebody eating an apple and make it sexual. But you invert that. The Secret Lives of Married Women has a bodice-ripper cover yet almost no sex in its pages at all. It’s not even about people trying to get some. So how is it so sexual?

Well, something I regularly grapple with is the fact that bdsm often doesn’t involve what we think of as sex. It doesn’t even have to involve bodily contact. There are people whose erotic gratification comes from being beaten, or polishing boots, or serving as a maid. I believe that people think of me as a sexual person, and I think of myself that way as well, but the truth is that, while I enjoy sex, it’s not the main event in my erotic life. My deepest erotic yearnings most often have to do with something much more abstract, like the intimacy between arch-enemies, or etiquette that approaches an art form, or perfect service, or flawless professional form, or the moments of reprieve within or following an interpersonal silence. And it’s been my experience that when you write your own strange truth, more people identify with it than you might have thought.

Wow: “Moments of reprieve within or following an interpersonal silence.” That does sound intriguing.

Well, as a rule, silences between people are laden with emotion and tension and projection and torment, and to me, they’re sexy. When I was growing up, one very formative influence on me was Chaim Potok’s The Chosen. A Hasidic father raises his son almost entirely in silence–he doesn’t talk to the boy at all unless they’re discussing Jewish theology. This is terribly painful for the son–Danny–but later he has this to say about it, to his friend Reuven: “You can listen to silence, Reuven. I’ve begun to realize that you can listen to silence and learn from it. It has a quality and dimension all its own. It talks to me sometimes. I feel myself alive in it. It talks. And I can hear it.”

Well, as a rule, silences between people are laden with emotion and tension and projection and torment, and to me, they’re sexy. When I was growing up, one very formative influence on me was Chaim Potok’s The Chosen. A Hasidic father raises his son almost entirely in silence–he doesn’t talk to the boy at all unless they’re discussing Jewish theology. This is terribly painful for the son–Danny–but later he has this to say about it, to his friend Reuven: “You can listen to silence, Reuven. I’ve begun to realize that you can listen to silence and learn from it. It has a quality and dimension all its own. It talks to me sometimes. I feel myself alive in it. It talks. And I can hear it.”

When I was in eighth grade, I had a very brief romance with a boy in my class, and after things went south, he wouldn’t speak to me. He managed–despite all my best efforts–to hold this silence for over a year. Sometimes a teacher would break the class into small groups to work on some project or other, and it was this incredibly awkward situation where even in these close quarters, he’d avoid looking at me or talking to me. Ironically, he was trying to write me off, to make me go away, but there was this hyper-awareness of each other within the silence that bound us together as a casual friendship could never have done. There’s an architectural phrase–“presence of absence”–and I think silence creates that. And so then sometimes there are these interludes within a silence where commerce is absolutely necessary–like when this guy was forced to talk to me within the context of a class exercise or something–and to me that’s like a window opening and closing again. It’s this strange and precious oasis within the desert, as laden as the silence is.

At a different time in my life (when I was in my early thirties), I read in the paper that an ex-boyfriend–who’d just published his first book to great acclaim–was scheduled to read at a local pub. Many years before, things had ended badly with him and he wasn’t willing to remain friends. We hadn’t seen each other or spoken in at least a decade. When I walked into the place, he was talking with some people by the bar. I tried to move past him with my head down, face averted, thinking maybe I’d speak to him later–after the reading, if at all–but without a break in his conversation, without even taking his gaze from his friends, he reached out and grabbed my arm.

Maybe silence is on the intimacy-with-enemies continuum for me. Here’s someone who wants nothing to do with you, or has deliberately had nothing to do with you for a very long time, but the intimacy remains, it’s almost a reflex of deep recognition. I’m intoxicated by moments like these.

And somewhere between eighth grade and your thirties you were a stripper. What did you learn about sexuality from that?

Well, I was far from the best or most beautiful dancer in any of the places I worked, and yet I made the most money, or almost the most, night after night. And I believe the reason for this is that I would have real conversations with the customers. I’d ask them questions about themselves and listen to their answers, and I always suspended judgment toward whatever they were telling me, and I was genuinely interested in much of what I heard. For me, this underscored the idea that physicality isn’t really at the heart of sexual allure. It helps, but it’s not enough; it doesn’t have staying power. I consider curiosity and self-revelation very potent forms of lust, and if you can gratify those impulses in another person, you’ll be irreplaceable in a way that a pretty face or hot body can never be.

So you stoked their lust by allowing them to reveal themselves to you, while you revealed your body. What was in it for you besides the money?

So you stoked their lust by allowing them to reveal themselves to you, while you revealed your body. What was in it for you besides the money?

In terms of what drew me to the job, I once wrote a whole essay on this topic, called Notes From The Catwalk. In it I said that I needed the attention, the affection, the adulation. I’d stand by that assessment today. Also the dynamics of dominance and submission were rampant in the strip joint, so the job was endlessly interesting to me for that reason.

Finally, it was a job that required only three nights of work a week. It brought in a lot of money, and yet all my days (and four of my nights) were free, and that was a great schedule for me, especially in terms of having time to write.

And while we’re on the subject of curiosity and self-revelation…. the women in Secret Lives are discovering and revealing their own deeper desires. I hesitate to say “deepest,” but I’ll ask you about that in a moment. The protagonists are twin sisters who seem like opposites: an actress/housewife with a semi-secret sexual past, and a buttoned-up, high-powered lawyer. Obviously one of them is starting from a deeper place, but do they ultimately want the same thing? Do you consider it something most women want?

I think it’s actually something that both men and women want. I think submission is a deep luxury that almost everyone wants, at least from time to time. In my experience, there are about a dozen submissives for every true dominant. It’s counter-intuitive, isn’t it? You’d think that most people would rather be a hammer than a nail, but I’m here to tell you it’s not so.

But then the women take charge of how they’re going to integrate their new-found desires into their lives. So who’s really in charge?

I certainly don’t think that identifying as a submissive means any sacrifice of agency or power in everyday life. Quite the opposite in fact–usually it’s powerful people who have the deepest desire to submit, perhaps because it allows them a break from the very difficult work of dominating.

Difficult in real life, but what about roleplaying–how hard is it to dominate people who wish to submit?

It’s tricky to characterize submissives as “people who wish to submit” because as anyone in the bdsm scene can tell you, submissives tend to be the most controlling and demanding bunch of people this world will ever see. I believe submissives are people who wish to enact the fantasy of submission, which is very different from actually submitting. Also, every submissive wants very different things. One might want to be tortured to within an inch of his life–to be branded, tasered, covered in hot wax, burned with cigarettes, etc.–and another might wish only to dress in a French maid’s uniform and dust your furniture. One might love to be called a slut, another might be deeply affronted by it. Every good bdsm relationship is a nuanced negotiation in which both partners strive to please. So it’s rarely easy, regardless of which role you inhabit.

It’s tricky to characterize submissives as “people who wish to submit” because as anyone in the bdsm scene can tell you, submissives tend to be the most controlling and demanding bunch of people this world will ever see. I believe submissives are people who wish to enact the fantasy of submission, which is very different from actually submitting. Also, every submissive wants very different things. One might want to be tortured to within an inch of his life–to be branded, tasered, covered in hot wax, burned with cigarettes, etc.–and another might wish only to dress in a French maid’s uniform and dust your furniture. One might love to be called a slut, another might be deeply affronted by it. Every good bdsm relationship is a nuanced negotiation in which both partners strive to please. So it’s rarely easy, regardless of which role you inhabit.

Then there’s Nan, a supporting character, whose submissiveness rules her life. She dedicates herself body and soul to a man who can offer her nothing sexually, who can’t even see her—he’s blind. Even after she’s banned from his life, she remains loyal to him in her mind. I didn’t want to say deepest before because Nan seems to suggest that there’s always deeper to go. But is this erotic submission or neurotic obsession? And she was raised by nuns—so is Abel, the blind man, taking over their role in her life, and does that imply that ultimately she wants to submit to a God?

I don’t think of Abel as having replaced the nuns, in Nan’s life. I think the more accurate description is an analogous one: Abel was to Nan what Christ was to the nuns. The average reader might think Nan is unhinged: after all, she’s invested her mind, heart and soul in a relationship where she believes–but can never be sure–that an unspoken understanding has been established. But any reader who believes in God probably makes a daily practice of loving and praising and worshiping and consulting and begging and thanking an entity which has never been seen or heard. Is Nan any more or less crazy than anyone who believes in God? I don’t think she is; I just see her as having chosen a different source of spiritual sustenance.

Last question: The Secret Lives of Married Women is your first book in twelve years…. What have you been doing?

I didn’t write a word for nearly a decade after publishing my second book in 2001. That book came out precisely on 9/11 and its inspiration was a firefighter I’d loved who died the very day it was published. For many reasons I don’t want to go into here, there was so much trauma surrounding that publication that I just couldn’t bring myself to write much more than a shopping list for a very long time. I broke into the business arena and–during that period–made much more money than I’d ever made as a writer, and I got married and had two children and moved to the west coast and did many other exciting and fulfilling things. But not writing for all those years was a source of very deep sadness for me and I’m glad it’s behind me now.

Me, too!

**********

The Secret Lives of Married Women is available on Amazon and from booksellers everywhere.

Leave a Reply